The First Computer: Technology that Changed the World

Once a unique marvel of technology, computers can be found just about everywhere these days. From massive server computers to tiny smartwatches, we live in a world ruled by them.

But this wasn’t always the case. Throughout this storied journey, there have been many firsts. These innovations were not always spectacular, but they were breakthroughs that paved the way for greatness, and the stories behind their invention are eventful, awe-inspiring, and, occasionally, glorious.

Join us as we delve into the history of computers with a look at some of the watershed moments in the field ranging from the first computers and the early 19th century all the way to the dawn of the modern computing age in 1990.

What Was the First Computer?

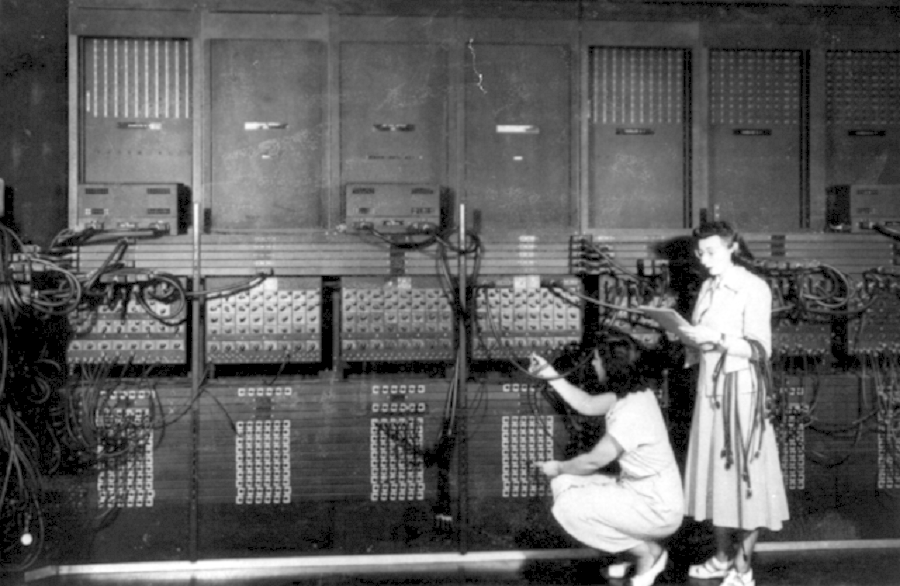

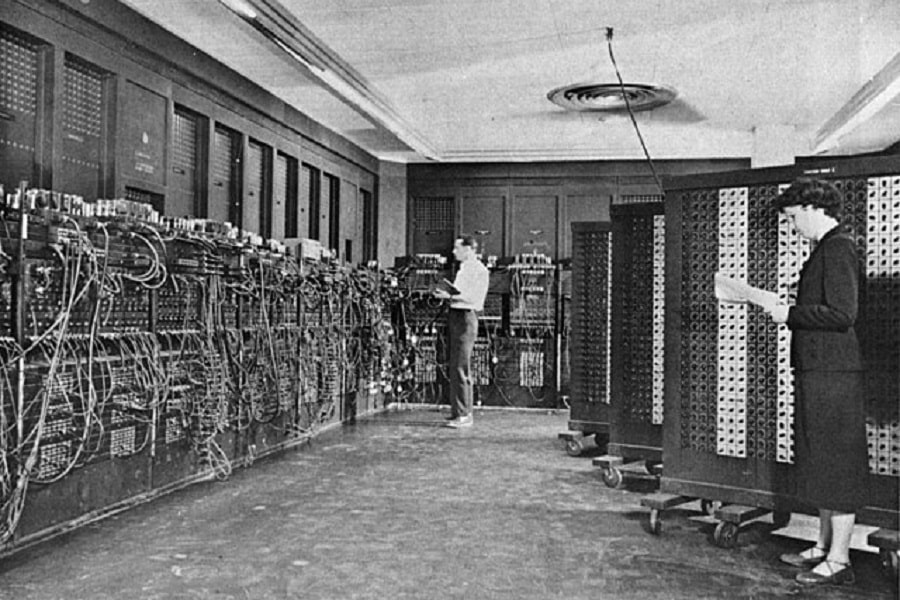

Two women wiring the right side of the ENIAC with a new program.

Two women wiring the right side of the ENIAC with a new program.

While the question is pretty straightforward, the answer can — surprisingly — vary widely depending on who you ask and what adjective (if any) you use before ‘computer.’ Some might cite the Difference Engine while others go as late as to ascribe the ENIAC with the honor.

To answer this question the most accurately, we have to go to the root of the word ‘computer.’ From the early 17th century till the mid-20th century, the word was assigned to people who did calculations (usually at high speed), or ‘computed.’ It wasn’t until machines that could perform the same tasks were invented that the word gradually shifted in meaning.

Considering this, the first computers, really, were humans.

With that out of the way, let’s get down to what you really came here for — technological breakthroughs.

Humble Beginnings: The First Mechanical Computer

While one could argue that there are plenty of ‘mechanical’ parts even in today’s computers, the term ‘mechanical computer’ essentially refers to machines that cannot run without mechanical forces being applied by the user. In contrast, digital computers are able to carry out their own operations using electricity.

Mục Lục

Difference Engine

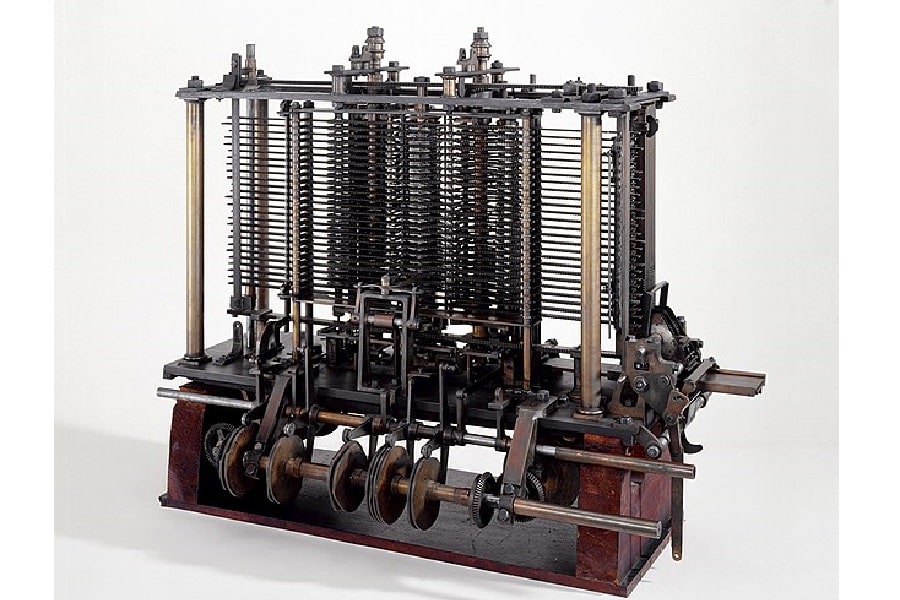

Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine

Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine

Although Frenchman Joseph Marie Jacquard’s punch card loom preceded it by some two decades, the first mechanical computer is almost universally accepted to have been Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine.

Although scholars cannot agree upon an exact date for when the English mathematician began work on his contraption, it is certain that development began sometime in the 1820s and continued well into the next decade.

While the steam-powered machine could — theoretically at least — carry out addition and subtraction, Babbage’s vision was to use it to calculate accurate logarithm tables. At the time, these tables were done by human computers who were — unsurprisingly — prone to human errors.

When logarithmic numbers are used for navigation, even the tiniest errors can lead to disaster, and Babbage intended to eliminate this problem with his invention.

However, due to a lack of funding, the project stalled in 1833 and the machine was never completed by Babbage.

Analytical Engine

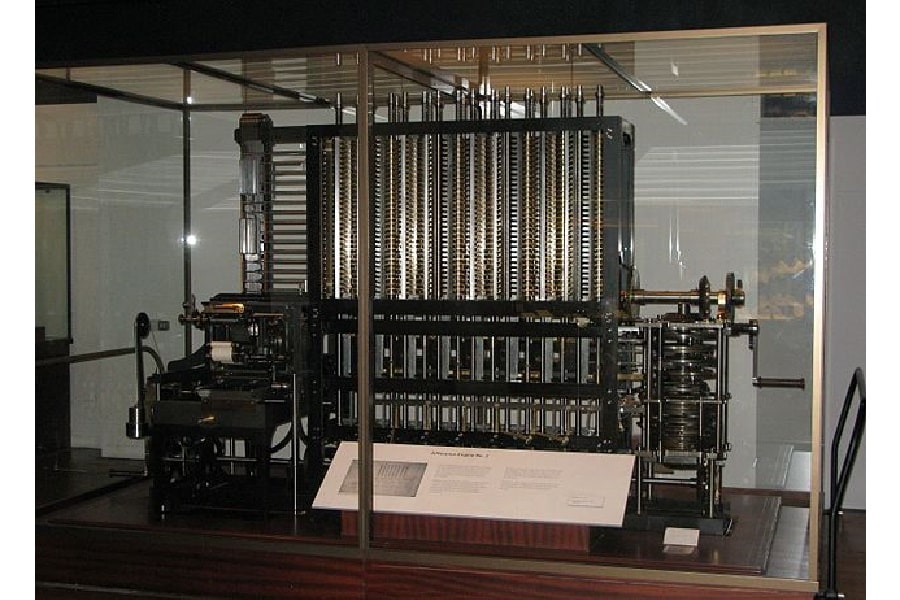

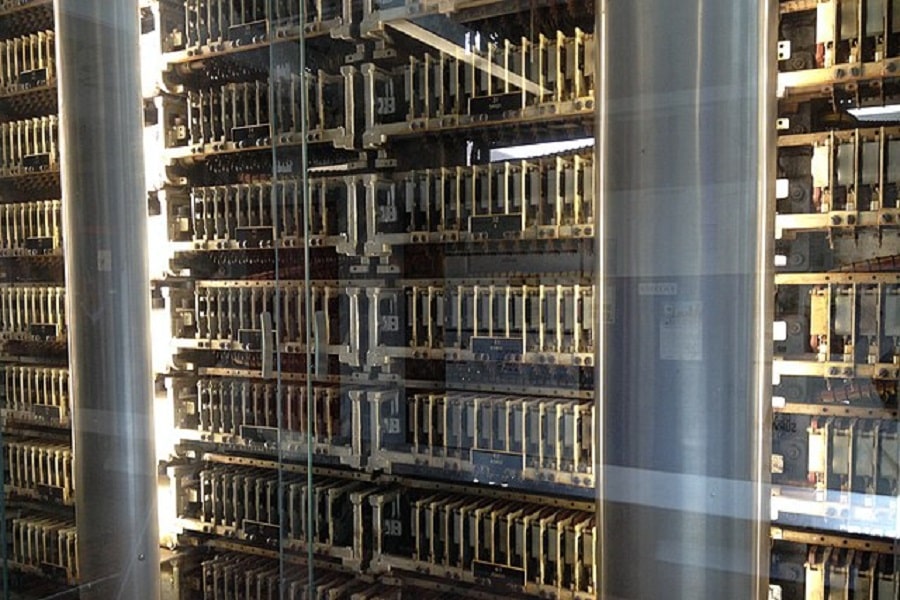

Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine

Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine

Not one to be daunted by misfortune or lack of appreciation, he set about planning his next project — the Analytical Engine — just 4 years later. Remember how we said ‘almost’ universally? That is because some consider the Analytical Engine to be the true pioneering idea behind modern computers rather than the one invented by Babbage.

Unlike the limited potential of its parent project, the Engine was conceptualized to be able to do multiplication and division as well. The machine essentially had four different parts, known as the mill, store, reader, and printer. These parts served the same purpose as components that are still standard features in the computers of today.

For instance, the mill was the means of computation, tantamount to the central processing unit. The store worked as a rudimentary form of memory, such as the RAM or hard disk on a modern computer. Finally, the reader and printer were essentially the input and output, with instructions being delivered via the former and results being taken from the latter.

The operation of the analytical engine was based on a system of punch cards much like Joseph Marie Jacquard’s loom, which would essentially make it program-controlled. In fact, English mathematician Ada Lovelace wrote an algorithm — what was essentially the world’s first ever computer program — for it in 1843. After becoming fascinated by the device while translating a French paper on it, she went on to create sets of instructions that would enable the machine to compute Bernoulli numbers.

Sadly, despite Babbage’s best efforts, the Analytical Engine never went past the prototype stage. Had it been completed, it would have been considered the world’s first mechanical digital computer. However, although it seemed that Babbage’s work and Lovelace’s first program went in vain — at least as far as application goes — their efforts would lay the groundwork for the digital world as we know it today.

Differential Analyzer

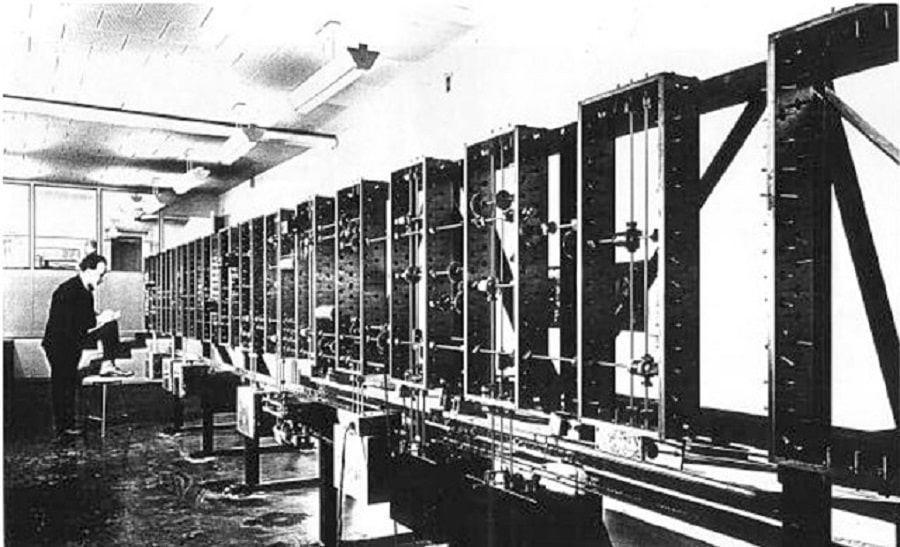

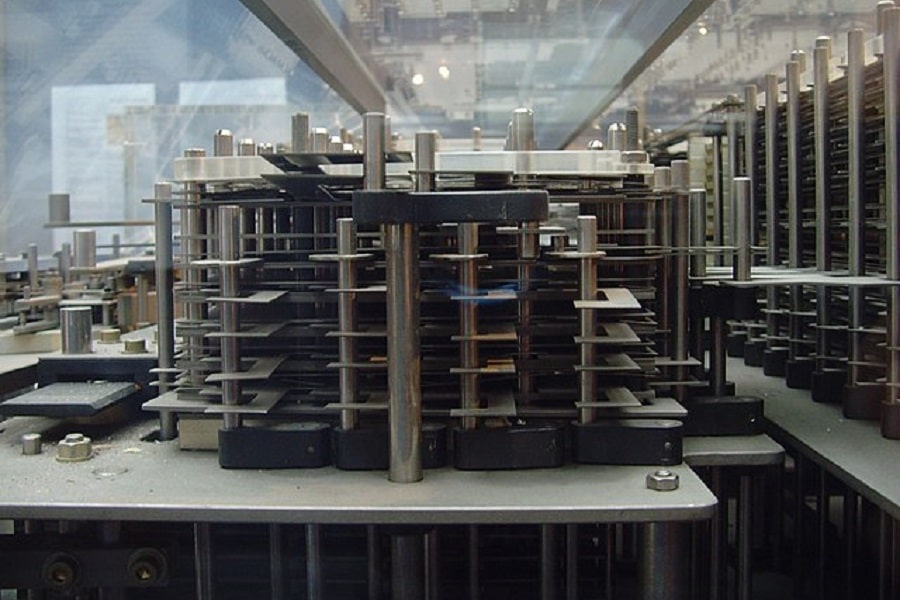

This machine constructed by Stig Ekelöf, inspired by Vannevar Bush’s mechanical differential analyzer.

This machine constructed by Stig Ekelöf, inspired by Vannevar Bush’s mechanical differential analyzer.

In 1931, Vannevar Bush, working for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, developed the Differential Analyzer. Using a complex system of gears, wheels, disks, and replaceable shafts, this complex contraption was able to solve differential equations. The electromechanical machine was in use at the university until it was superseded by improved technology in the 1950s.

Bell Labs Model II/Relay Interpolator

Twelve years after Bush, Bell Labs came up with their revolutionary relay interpolator. Using a whopping (for its time) 440 relays, this analog machine was used to direct artillery guns using mathematics for pinpoint accuracy. It was programmed using paper tape, and following the war, Model II was decommissioned from military duty and used for other projects.

IBM ASCC/Harvard Mark I

The backside of the Harvard Mark I

The backside of the Harvard Mark I

In 1944, there was one last hurrah for the analog computer with Howard Aiken and IBM finishing up the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, or ASCC. This machine was basically an improved incarnation of what Babbage envisioned with his Analytical Engine, and it served pretty much the same purpose. The Mark I also holds the distinction of being one of the first mainframe computers.

Into a New Era: The First Digital Computer

Although there were a few more minute steps on the road to full-fledged digital computing, such as Georg and Edvard Scheutz’s 1853 printing calculator or Herman Hollerith’s 1890 punch-card system, it wasn’t until well into the 20th century that early digital computers began to appear.

The advent of the digital computer age is a murky affair, with different groups accrediting different machines with the accolade of being the very first ‘digital computer.’ There are three prime candidates that take the podium on this: the Atanasoff-Berry Computer, the Zuse series, and the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, or ENIAC.

Zuse Z1 – Z4

Zuse Z1

Zuse Z1

Developed by German engineer Konrad Zuse, the Z1 was the first computer to use binary codes to represent numbers. Completed in 1938, the machine’s revolutionary nature was overshadowed by the fact that its computations were far from reliable.

Its 1941 successor, the fully automatic, digital Z3 was the first programmable computer. The computer instructions for this electromechanical wonder had to be fed into it with punch cards made of film.

Although undoubtedly a fantastic invention, the device’s utility was not recognized by the higher-ups of the Third Reich, and it was eventually unwittingly destroyed by Allied bombers during a raid on Berlin in December 1943, during the height of World War II.

This did not deter Zuse, however, as he went on to attempt a succeeding Z4 afterward. This machine not only survived the war but with its floating point binary arithmetic capabilities, went on to become one of the first commercial digital machines.

Atanasoff-Berry Computer

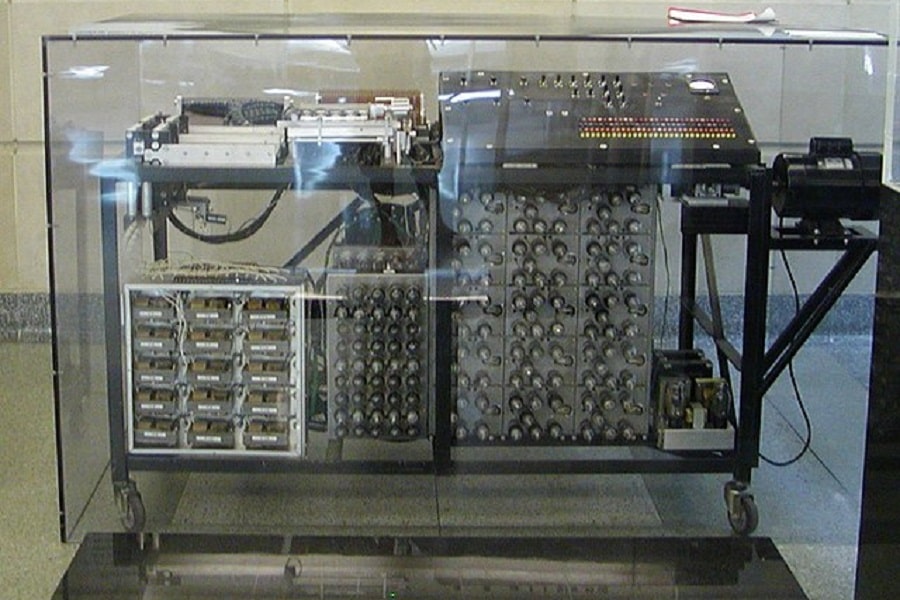

Atanasoff-Berry Computer

Atanasoff-Berry Computer

Considered to be the first electronic digital computer to be fully automated — which separates it from the electromechanical Z3 — the Atanasoff-Berry is the least celebrated of the three aforementioned machines. Completed in 1942 at Iowa State University by John Vincent Atanasoff and his graduate student Clifford Berry, the machine sometimes called the ABC was the pioneer in using vacuum tubes to carry out calculations — a process that would be replicated for the British Colossus computer a year later. Unfortunately, ABC wasn’t programmable, which greatly reduced both its historical importance and popularity at the time.

ENIAC

ENIAC in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

ENIAC in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Starting in 1943, John Mauchly and J Presper Eckert Jr, a physicist and an engineer working at the University of Pennsylvania, began working on the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, or ENIAC. This is widely touted as the first general-purpose programmable electronic digital computer.

Despite being widely regarded with those adjectives, the ENIAC was far from being a truly general-purpose computer or even programmable. For starters, it had to be programmed to compute using plugboards, and while this greatly increased its calculation speeds, it could take up to hundreds of hours to reprogram it. Moreover, it was specifically designed for the very particular purpose of calculating ranges for artillery during the still-very-much-raging World War II, which made it a much more niche machine than it is made out to be.

The Age of Procedure: The First Stored Program Computer

With programmable computers becoming the norm, the need for storage became obvious, and the first practical stored program computer — the Manchester Baby (later Mark I) — was built.

The Manchester Baby

Photo of the recreation of the Manchester Baby

Photo of the recreation of the Manchester Baby

Initially called the Small-Scale Experimental Machine or SSEM, the Manchester Baby was assembled at the University of Manchester. The brainchild of Tom Kilburn, Frederic C Williams, and Geoff Tootill, the machine was used to run the first-ever stored program on June 21, 1948. Carrying just 17 instructions, the program became the first to function on an electronic, digitally stored-program device.

Despite this milestone, it wouldn’t be until the second half of the following year that the machine would be deemed complete and given the more respectable-sounding name of Manchester Mark I.

Finding a Greater Purpose: The First Commercial Computer

With computers firmly established as the key to the future, businesses, universities, and organizations began to take an interest in them. It was thus that the era of the commercial computer began, with the UNIVAC.

UNIVAC

A Census Bureau employee operates one of the agency’s UNIVAC 1100 series computers.

A Census Bureau employee operates one of the agency’s UNIVAC 1100 series computers.

The Universal Automatic Computer, built by the Eckert-Mauchley Computer Corporation, was a successor to the aforementioned ENIAC. Boasting much more computational power and better utility, the electronic digital machines had stored programs and were immediately recognized by many groups as an incredible tool.

It was the US Census Bureau that purchased the first UNIVAC 1, making it the first computer to change hands in exchange for money. The UNIVAC brand would later change hands, going to the typewriter giant Remington Rand, and continue to be produced commercially with new models coming out until as late as 1986.

The UNIVAC was followed by the Zuse Z4 and the Ferranti Mark I soon after, and the age of commercial computers had truly begun.

Going Mainstream: The First Mass-Produced Computer

The success of the aforementioned trio, along with a number of new companies entering the computer market, made even more companies realize the importance of these devices. It wasn’t long before computers, like every other piece of machinery in the modern world, were being mass-produced. The first of this kind was the IBM 650 Magnetic Drum Data-Processing Machine.

IBM 650

The IBM 650 computer at Toyo Kogyo

The IBM 650 computer at Toyo Kogyo

Beginning its production in 1954, the 650 featured its namesake magnetic drum, which provided much quicker access to stored data than any previous computer. Additionally, its relative ease of use, lower price, programmability, and customizability led to widespread popularity, with the machine finding a home not only with businesses but universities as well. It was with these machines that the first generation of then-future professional programmers learned their trade. The 650 saw 2,000 units being produced by 1962, with IBM providing support until 1969.

Bigger and Better: The First Computer with a Hard Disk Drive

It’s hard to imagine now, but there was a time when a hard disk drive wasn’t an essential part of a regular computer. This changed with the RAMAC.

IBM RAMAC 305

IBM 305 RAMAC system

IBM 305 RAMAC system

You don’t forge an empire lasting well over a century without some terrific innovations on your résumé, and IBM’s 1956 RAMAC (Random Access Method of Accounting and Control) 305 was one such beauty. The gigantic disk drive of the RAMAC was the first magnetic disk storage ever made, and it was capable of storing in the ballpark of 5 megabytes of data. Unlike the tape, film, or punch cards before it, the RAMAC was the first machine to allow true real-time random access to the entirety of the data that it contained.

To the Masses: The First Personal Computer

Like the first mechanical computer, what you consider to be the ‘first personal computer’ depends greatly upon what you consider a personal computer to be, to begin with. While there are quite a few possible entries for the debate — such as the Simon, the Micral, and the IBM 610, the biggest divide exists between two early computers: the Kenbak-1 and the Datapoint 2200.

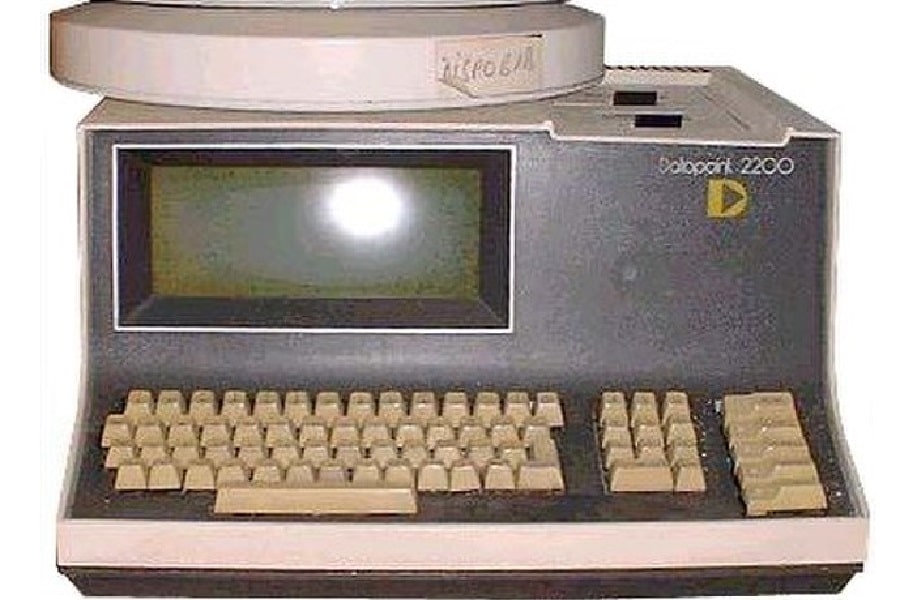

Datapoint 2200

Datapoint 2200, Terminal Personal computer, 1970

Datapoint 2200, Terminal Personal computer, 1970

The Datapoint 2200 was designed by Phil Ray and Gus Roche of Computer Terminal Corporation or CTC, which would go on to be renamed Datapoint. Running on what would later become the revolutionary Intel 8008 processor, the 2200 had all the hallmarks of a modern personal computer, such as a display output, a keyboard, and an operating system. Coming out in June 1970, it also came with 2 Kilobytes of RAM, but this could be increased to 16K.

An incredible achievement for the time, this machine also had two tape drives and had optional add-ons such as a floppy drive, modems, printers, hard disks, and even LAN capabilities using ARCnet.

Although the 2200 would quickly get superseded, its Intel 8008 processor would go on to form the foundation of the 8-bit computing era.

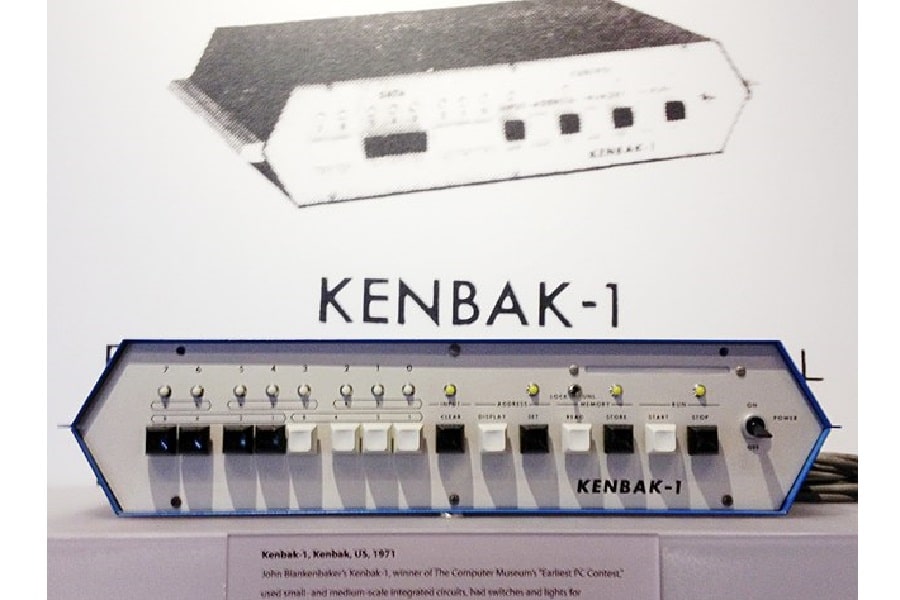

Kenbak-1

Kenbak-1

Kenbak-1

Unlike the Datapoint 2200, the Kenbak-1 was much simpler. The brainchild of John V Blankenbaker, the device did not feature a microprocessor as it was developed before the Intel 4004 hit markets in 1971. Lacking a proper display terminal, the Kenbak-1 used LEDs to output information. Although released after the Datapoint 2200 and lacking some of the same features, it was a self-sufficient unit and is thus widely regarded as the first personal computer.

Enhancing the Visual Element: The First Computer with a Graphical User Interface

With Ivan Sutherland’s 1963 program Sketchpad and Douglas Engelbart’s Mother of All Demos in 1968 showing the possibilities computers could open up in the world of graphics, the future of the industry was set. Five years after the landmark events of the demo, the world saw the launch of the first computer with a graphical user interface.

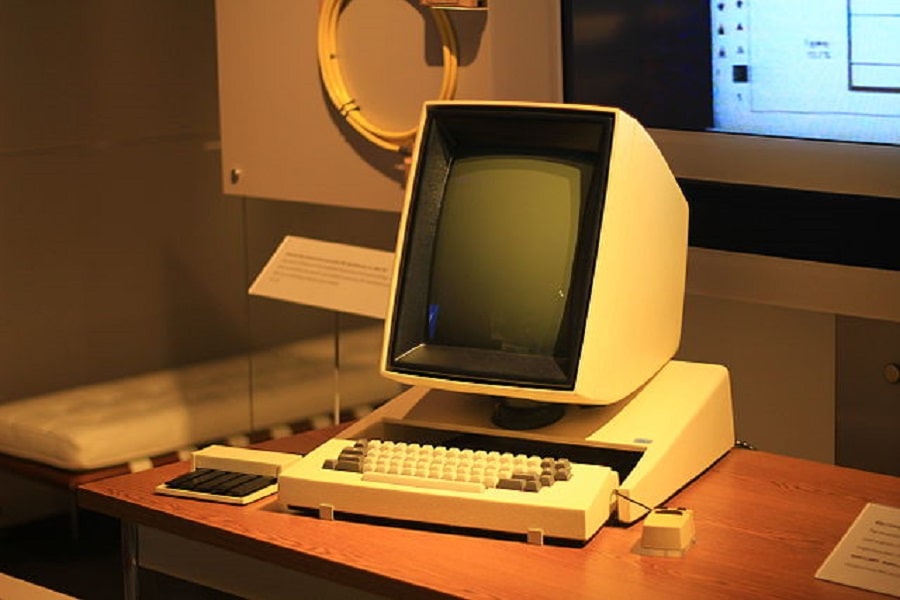

Xerox Alto

Xerox PARC Alto with mouse and chorded keyset

Xerox PARC Alto with mouse and chorded keyset

Running on the Alto Executive operating system, the Xerox Alto was the first computer to feature an interface based on graphics instead of text. Replete with windows for separate programs, this monochrome marvel was one of the first computers to ship with a mouse and was essentially the first desktop computer when it was released in 1973. Despite this breakthrough, however, the cost and relatively low work rate of the machine gave it much less utility, with just over 2,000 of its two direct variants ever being produced.

Household Names: The First Commercially Successful Personal Computers

Until the mid-70s, computers had largely been for businesses, government offices, and scientific and industrial research. However, all that changed in 1974 with the advent of the Altair 8800, and later the product that would put an Apple computer at the top of everyone’s wish lists. Although several competitor products — such as the Commodore PET and the Tandy TRS-80 — made their own mark in the industry, they didn’t reach the iconic status shared by the aforementioned duo.

Altair 8800

Altair 8800

Altair 8800

Built heavily on the Intel 8080 CPU by Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems — or MITS — the machine went largely unnoticed until it found a place on the cover of Popular Electronics magazine in January 1975. In the months that followed, the Altair would single-handedly set off the microcomputer boom that led to the world as we know it today. Sold as a computer kit, it took over the market in the mid-70s.

Like the Kenbak-1, the 8800 lacked a display, relying instead on printed outputs. However, its relative affordability and excellent utility gave it an edge over other computers of the day, which led to its increased popularity.

Apple II

Apple II

Apple II

If the Altar 8800 laid the seeds of the microcomputer revolution, the Apple II was the plant that truly bloomed. With roughly 4.8 million units sold, it changed the way people looked at computers. Suddenly, every large-scale business of any repute had to have them for their executives.

First introduced at the West Coast Computer Faire in April 1977, the product caught the attention of tech experts and enthusiasts alike. The Apple was available with anywhere between 4 to 64 Kilobytes of memory and could come with either 16-color low-resolution or 6-color high-resolution graphics. It also had a 1-bit speaker and cassette input/output built-in, and a year after its release, a floppy disk drive called the Disk ][ was made available for an additional cost.

Although it was discontinued just two years later, it kept selling for well over a decade, and Apple even distributed them in schools to give the newer generation a glimpse into the world of computers, which until then had been very much adult territory. Thus, variants and successors of this seminal device continued to shape the world of computing for decades afterward.

A New Generation: Computing Breakthroughs in the 80s

There were so many advancements in the world of computing in the 80s that it’s hard to single out firsts. The 80s saw progress in both the home and office computer markets. While the personal computer boom was in full flow, most computers in the late 70s were still found only in offices and schools, with home the home computer market mostly belonging to hobbyists or people with technical backgrounds. With a personal computer’s high cost and complexity of use deterring untrained, amateur home users from making such a sizable commitment, newer products were introduced which got home users to embrace computers.

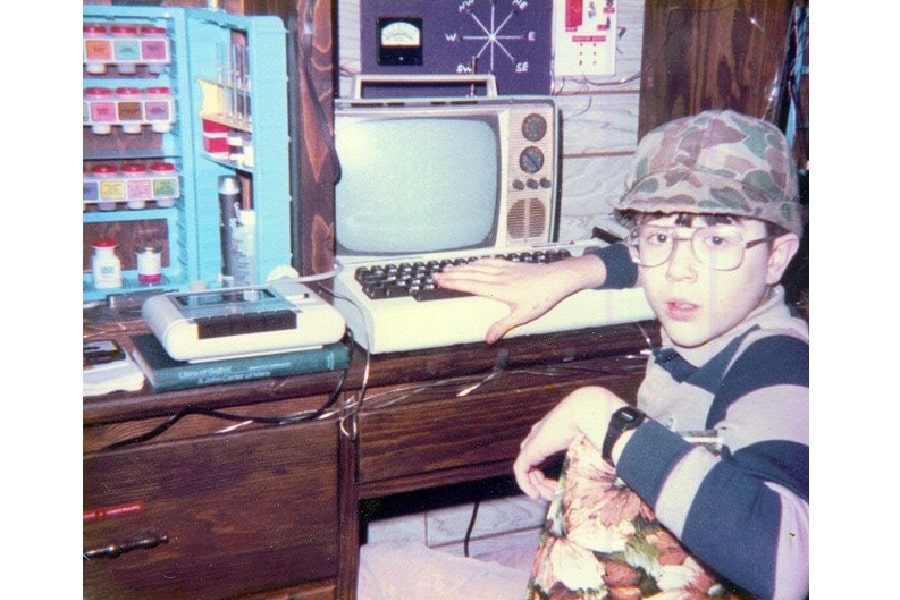

Commodore VIC-20/C64

A boy with Commodore VIC-20

A boy with Commodore VIC-20

Following the success of the PET, Commodore came up with the VIC-20 in 1981. While the device lacked an output device, it could be hooked up to a CRT screen. It soon became popular for both its work utility and for the sheer number of video games available on it.

The VIC-20 boasted a processor that ran at just over 1 MHz, with the exact maximum frequency depending on the kind of video signal being used. While its 5KB (upgradeable to 32) RAM was less than the Apple II’s 64KB cap, it was nevertheless a great entry-level machine.

The VIC-20 also came with optional tape input, floppy disk drive, and cartridge port, and featured a resolution of 176×184 with 3 bits per pixel.

Its 1982 successor, the Commodore 64, was one of the first machines to incorporate 16-color capabilities, which made it extremely popular in the home gaming market. As far as raw specs went, it was very similar to its predecessor, with improvements coming mostly in the form of sound and graphics. The 64 was the biggest hit Amiga ever had, and it was produced and sold well into the 90s.

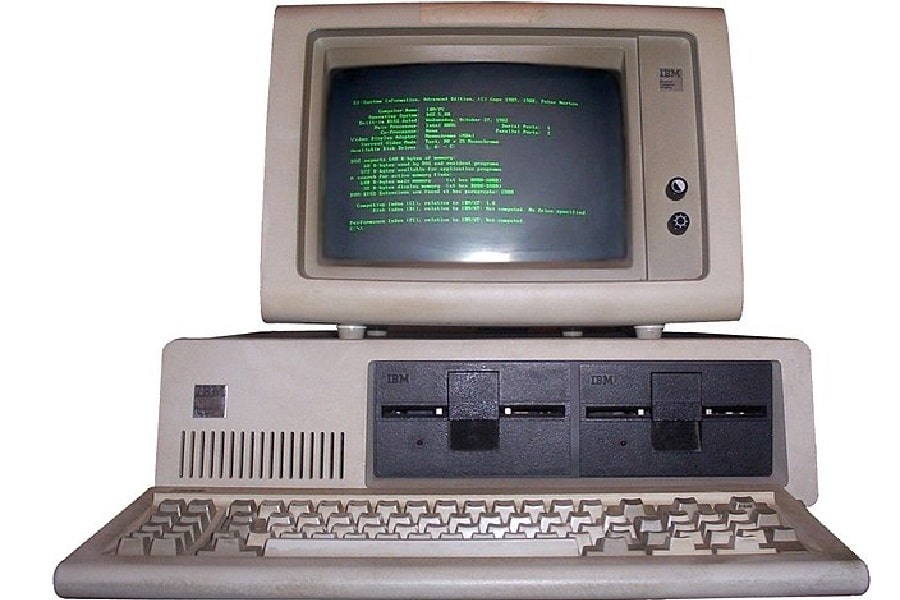

IBM PC

IBM PC

IBM PC

With the Apple II’s edge waning and the 1980s Apple III failing to capture the market like its predecessor, IBM stepped in to fill the market share with the aptly-nick-named PC.

The Model 5150 — as it was known to the tech circle — came out in 1981 and ran the first version of Microsoft’s groundbreaking Disk Operating System (or MS-DOS), and with a 4.77 MHz Intel 8088 at its core and possible RAM expansions going up to 256KB, the PC was a beast of a machine. It also featured both monochrome and color graphics options to please those who needed either.

Although far more expensive than the VIC-20, it was the be-all-end-all of microcomputers at the time of its release.

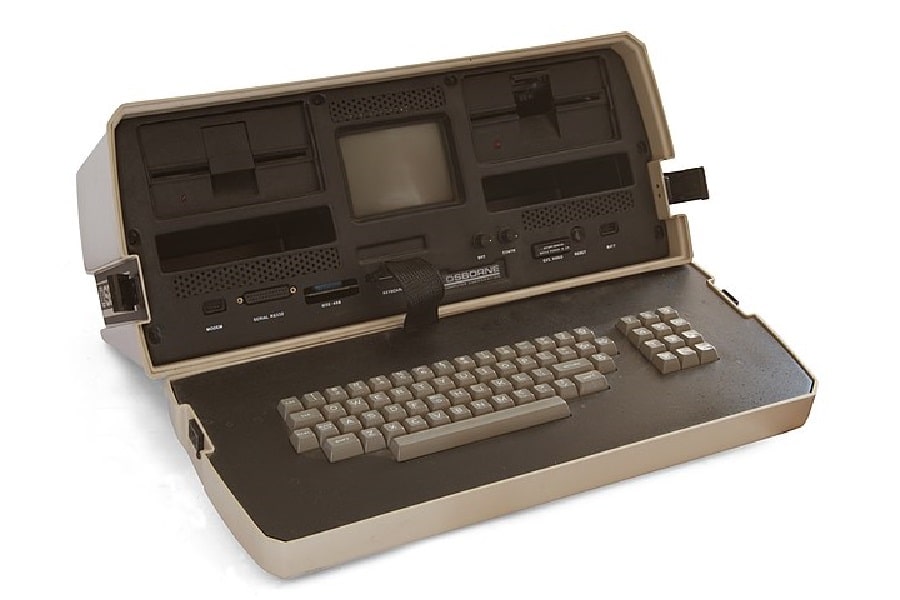

Osborne 1

Osborne 1

Osborne 1

While giants such as Apple, Commodore, and IBM were duking it out in the personal computer field, a lesser-known firm called Osborne Computer Corporation was hard at work with something even more futuristic — the first portable computer to attain commercial success.

Released shortly before the IBM PC, the Osborne 1 packed quite a punch for its size in terms of computational power. With 64KB RAM and a 4 MHz processor, it easily stood up to just about any personal computer in 1981, when it was released.

However, its monochrome display was a mere 5 inches wide, and it weighed a staggering 24.5 pounds, making it unfeasible for anyone to carry it around for too long. More importantly, Compaq would come in soon with their own take on the portable computer, which eventually drove the Osborne 1 out of the market.

Apple Lisa

Apple Lisa

Apple Lisa

The Xerox Alto may have made the GUI a reality, but the Apple Lisa brought it to the mainstream in 1983. The acronym of Local Integrated Software Architecture, the original Lisa came with a beastly 1MB of RAM, which was four times the maximum offered by the IBM PC, albeit with only a slight increase in processor speed. It also had a much larger monochrome screen.

However, its price was far too high for a modern computer of the time, and like the Apple III before it, it was soon deemed a failure. The Lisa’s story didn’t end there, however, as a lower-end iteration soon entered the market, only to eventually be rebranded into the high-end version of our next entry.

Macintosh 128K/512K/Plus

Macintosh 128K

Macintosh 128K

The Macintosh 128K was the popular lower-end machine that Apple needed to compete with other microcomputers. With a compact structure, relatively lightweight, and decent specs (6 MHz processor with 128K RAM), the Macintosh was a huge hit with those looking to avail Apple quality on a lower scale.

It wasn’t just the hardware that made the Macintosh stand out, though, as it was the first computer to use Apple’s revolutionary Mac OS. For 1984, it was a massive step forward.

The Macintosh name was also given to the less-powerful variant of the Lisa when it was rebranded, with the moniker 512K distinguishing its improved abilities. This would eventually give way to the even more powerful, legendary Macintosh Plus.

Compaq Deskpro

Compaq Deskpro

Compaq Deskpro

Although originally released in 1984 with a 286 processor, it was the Deskpro’s 1986 iteration that made the biggest splash as the first-ever 32-bit machine with a 386 processor.

This was a massive boost at the time, and the fact the much less popular Compaq beat tech giants IBM to the first 386-powered PC (IBM’s came out a few months later).

IBM PS/2

IBM Personal System2, Model 25

IBM Personal System2, Model 25

IBM’s PS/2 or Personal System/2 was released in April 1987 to great acclaim. It was not only better than IBM’s previous offers but also broke technological ground by being the first computer to come with a VGA adapter.

On the other hand, IBM’s proprietary attitude towards the new technologies introduced via the PS/2 as a result of the massive cloning of its earlier PC left other companies unhappy.

The PS/2 was also the last great technological leap of the 80s, and the decade closed with the device still being the norm.

Frequently Asked Questions About the History of Computers

With many important milestones having been touched, in this section, we will answer common questions regarding the history of computers and computing.

What was the first programming language?

The first true programming language ever developed was called Plankalkül. It was created in the early 40s by Konrad Zuse.

What was the first silicon chip made?

The very first silicon computer chip was created in 1961 by engineers Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce.

What was the first computer to implement the integrated circuit?

The IBM 360 — otherwise known as the IBM System — was the first computer to include integrated circuits in its construction.

What is a Universal Turing Machine?

Otherwise known as Universal Computing Machines, these are computers that are capable of simulating any other Turing machine (named after Alan Turing, considered one of the fathers of modern computing) when given an arbitrary input.

What was the ‘Mother of All Demos?’

Although this wasn’t its original name, the demonstration event itself was a landmark moment in the history of computing. Taking place on December 9, 1968, it showcased futuristic technologies such as a GUI with windows, a mouse, word processing, real-time remote text editing, and even video conferencing.

When was the mouse invented?

While the mouse was initially developed by Douglas Engelbart, whom you may remember from the Mother of All Demos, it was Bill English who created the very first prototype of the peripheral.

When was the first email sent?

The very first email was launched back in 1971 by Ray Tomlinson. Putting two computers right next to each other and connecting them using a system called ARPANET, a technology built for the military some 2 decades before this, Tomlinson was able to relay a message between the two machines.

When was the first version of Windows released?

The first ever version of Windows, Windows 1, was released by Microsoft in November 1985.

Want to learn more about technology in ancient times? Read 15 Examples of Fascinating and Advanced Ancient Technology You Need To Check Out.

Past, Present, and Future

Computers have slowly become a part of not only our daily lives, but a part of our society, culture, and even identity as a species. We have moved far beyond the slow improvements of the mid-20th century, with operating systems, computer language, and hardware evolving rapidly.

While it is impossible to think of a world without these essential devices, perhaps one day computers will become as obsolete to humans as their former alternatives feel now. Until then, however, computers are here to stay.

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)