Modern C# Hello World – NDepend

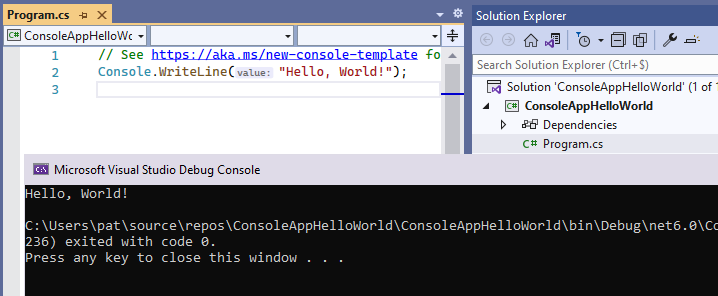

With Visual Studio 2022 when you create a new console project based on .NET 6, the Hello World source code generated is now as simple as that:

1

Console

.

WriteLine

(

“Hello, World!”

)

;

Nice and concise isn’t it? Here is what running this program looks like:

In Visual Studio 2019, the Hello World source code proposed when creating a new console project used to be much more verbose with the definition of a namespace, a class and a Main() method.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

using

System

;

namespace

ConsoleApp10

{

class

Program

{

static

void

Main

(

string

[

]

args

)

{

Console

.

WriteLine

(

“Hello World!”

)

;

}

}

}

Mục Lục

C# Hello World for Beginners

(If you are already experienced with C# just skip this section)

If you are a beginner you might want to know that:

- A class is required because C# is an Object-Oriented language: No code can be specified outside of a class.

- A method

Main()is required to start a C# program. This is why the methodMain()is qualified as an entry-point method. - Namespace are used to group the various classes of a program into logical units. The word logical is important because a namespace doesn’t refer to anything physical like a file, a directory or even a compiled element. When a class

Foois declared in a namespaceBar, the full name of the class isBar.Foo. You can either refer to this class with its full nameBar.Foo, or use the shorter nameFooas long as a clauseusing Bar;is declared prior to the usage ofFooin the source file so the compiler can guess that the code refers to theBar.Fooclass. - C# 9 and C# 10 introduces some new features to automatically generate and take care of the class

Program, the methodMain()and the namespaces stuff. As a result you don’t need to know more about these concepts before writing your code directly in the source fileProgram.cs. For example here is a small program that prints the 20 first Fibonacci numbers:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// Print on console the 20x first Fibonacci numbers

int

length

=

20

;

int

a

=

0

,

b

=

1

,

c

=

0

;

Console

.

Write

(

“{0} {1}”

,

a

,

b

)

;

for

(

int

i

=

2

;

i

<

length

;

i

++

)

{

c

=

a

+

b

;

Console

.

Write

(

” {0}”

,

c

)

;

a

=

b

;

b

=

c

;

}

Now let’s dig into what’s happening behind.

C# Hello World for Experienced C# Programmers

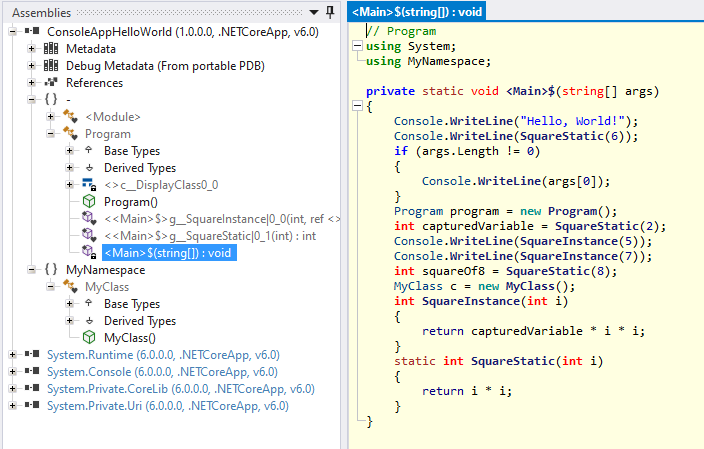

If you are already programming with C# for a while, let’s first decompile the assembly generated with IL Spy and realize that the compiled code is almost identical to the Visual Studio 2019 Hello World program shown in introduction.

Here are the new C# 9 and C# 10 features that makes possible one of the shortest Hello World source code in the industry:

- C# 9 Top-level statements

- C# 10 Implicit using directives

- C# 10 Global using directives

C# 9 Top-level statements

With top-level statements, C# 9 takes care of generating a class named Program with a method named <Main>$() that is de-facto the entry point of the executable assembly.

The top-level statements feature is quite flexible. Here is what you can do with it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

// Using clause can be declared before the first top-level statement

using

MyNamespace

;

Console

.

WriteLine

(

“Hello, World!”

)

;

// More than one top-level statements can be provided

Console

.

WriteLine

(

SquareInstance

(

5

)

)

;

Console

.

WriteLine

(

SquareStatic

(

6

)

)

;

// Per convention the main method is defined with an args parameter: <Main>$(string[] args);

// Thus you can use the parameter args to get console parameters.

if

(

args

.

Length

>

0

)

{

Console

.

WriteLine

(

args

[

0

]

)

;

}

// Program is not a static class thus it can be instantiated.

// However no method nor field can be declared in this generated class!

var

program

=

new

Program

(

)

;

// When declaring some methods after top-level statements,

// they are declared as local function of <Main>$

int

capturedVariable

=

SquareStatic

(

2

)

;

Console

.

WriteLine

(

SquareInstance

(

5

)

)

;

int

SquareInstance

(

int

i

)

=

>

capturedVariable

*

i

*

i

;

static

int

SquareStatic

(

int

i

)

=

>

i

*

i

;

// Top-level statements can be provided after local functions

Console

.

WriteLine

(

SquareInstance

(

7

)

)

;

// squareOf8 is not a field of the class Program but a variable of the method <Main>$()

int

squareOf8

=

SquareStatic

(

8

)

;

// The using MyNamespace; clause is used here to resolve MyClass.

Program

c

=

new

MyClass

(

)

;

// Namespaces and types can be declared after the last top-level statement

namespace

MyNamespace

{

// Program is not sealed and can be used as a base class. Pretty useless isn’it?

class

MyClass

:

Program

{

}

}

Here is the decompiled assembly if you are curious (like me):

However there are a few limitations with C#9 top-level statements:

- Only one source file of a C# project can contain top-level statements. This makes sense since there cannot be more than one entry-point method for an executable assembly.

- The C# project must generate an executable assembly. Obviously a library assembly doesn’t have an entry-point.

- The

<Main>$()

method cannot be called by user code since its identifier is not a valid C# identifier. However

<Main>$

is a valid CLR identifier, hence the runtime can invoke it to start the program.

C# 10 Implicit using directives.

In the minimal Console.WriteLine("Hello, World!"); source code, the class Console is declared in the namespace System. Thus, until now we had to declare a using System; clause for the C# compiler to resolve the class Console in the namespace System. However C# 10 implicit using directives makes this using clause useless.

If we look in the C# .csproj project file generated, we can see the XML element <ImplicitUsings>enable</ImplicitUsings>. The value disable is also possible which is equivalent to removing this XML element.

When the element <ImplicitUsings> has the value enable, a file named YourProjectName.GlobalUsings.g.cs is added in .\obj\Debug\net6.0. This source file is auto-generated at compile-time and must not be edited, else changes are erased at next compilation. For the above Hello World console application the content of this generated file is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// <auto-generated/>

global

using

global

:

:

System

;

global

using

global

:

:

System

.

Collections

.

Generic

;

global

using

global

:

:

System

.

IO

;

global

using

global

:

:

System

.

Linq

;

global

using

global

:

:

System

.

Net

.

Http

;

global

using

global

:

:

System

.

Threading

;

global

using

global

:

:

System

.

Threading

.

Tasks

;

We’ll detail the usage of the keyword global in the next section.

This file let’s you know which namepaces are imported by the compiler. The set of namespaces imported can be changed with some tags <Using> in the .csproj project file. The source file YourProjectName.GlobalUsings.g.cs is then updated to reflect the modified set of namespaces imported.

1

2

3

4

<ItemGroup>

<Using

Remove

=

“System.Linq”

/>

<Using

Include

=

“System.Diagnostics”

/>

</ItemGroup>

Notice that the set of namespaces implicitly imported depends on the kind of project. Those listed above are for a console project. But for an ASP.NET Core application some namespaces like Microsoft.AspNetCore.Http or Microsoft.AspNetCore.Builder are implicitly imported in addition to the ones imported for a console project. When in doubt, just create a blank project of your choice and double check the generated GlobalUsings.g.cs file.

C# 10 Global using directives,

In the YourProjectName.GlobalUsings.g.cs content we saw the new C#10 syntax with the keyword global using. It means that the specified namespace is imported for all C# source files of the current project. There are two way to use this feature:

- Either declare

global using YourNamespaceonce in a source file of the project. - Or specify

<Using Include="YourNamespace">in the .csproj project file. This way works even when no<ImplicitUsings>element is specified.

The global using directive only works at the project level. To make it work at the solution level, several strategies A) B) C) D) can be adopted:

- A) You can just define a source file named

GlobalImports.cswith theglobal usingclauses, and reference this source file from all C# projects of the solution. - B) You might already have an

AssemblyInfo.csfile shared among all projects that can also be used to declareglobal usingclauses. - C) Another option is to declare the

<Using Include="YourNamespace">XML element in a shared Directory.Build.props file located at the root of your repository. This opens a new range of flexibility. For example you might want a global using clause likeusing NUnit.Framework;only for projects which haveTestin name. This can be achieved with a Directory.Build.props file whose content is:

1

2

3

4

5

<Project>

<ItemGroup

Condition

=

“$(MSBuildProjectName.Contains(‘Test’))”

>

<Using

Include

=

“NUnit.Framework”

/>

</ItemGroup>

</Project>

- D) You might prefer to put all you global using clauses for tests in a file

.\Shared\GlobalUsingsTests.csand include this file for all projects which haveTestin name. The Directory.Build.props file content can then be:

1

2

3

4

5

<Project>

<ItemGroup

Condition

=

“$(MSBuildProjectName.Contains(‘Test’))”

>

<Compile

Include

=

“.\Shared\GlobalUsings4Tests.cs”

/>

</ItemGroup>

</Project>

Finally let’s notice that in this using clause below…

1

global

using

global

:

:

System

;

…global:: has noting to do with the global using feature. It’s here to avoid some collisions when several types or namespaces with a same name are declared in various scopes (full explanation here).

Conclusion

This article explained some new C# features that are here to reduce the size of your C# sources. A beginner doesn’t even need to know what a class or a method is to start writing a small working program. On the other hand, the feature implicit and global using directives are flexible enough to discard thousands of using clauses in any real-world application.

Patrick Smacchia

My dad being an early programmer in the 70’s, I have been fortunate to switch from playing with Lego, to program my own micro-games, when I was still a kid. Since then I never stop programming.

I graduated in Mathematics and Software engineering. After a decade of C++ programming and consultancy, I got interested in the brand new .NET platform in 2002. I had the chance to write the best-seller book (in French) on .NET and C#, published by O’Reilly and also did manage some academic and professional courses on the platform and C#.

Over my consulting years I built an expertise about the architecture, the evolution and the maintenance challenges of large & complex real-world applications. It seemed like the spaghetti & entangled monolithic legacy concerned every sufficiently large team. As a consequence, I got interested in static code analysis and started the project NDepend in 2004.

Nowadays NDepend is a full-fledged Independent Software Vendor (ISV). With more than 12.000 client companies, including many of the Fortune 500 ones, NDepend offers deeper insight and full control on their application to a wide range of professional users around the world.

I live with my wife and our twin kids Léna and Paul in the beautiful island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean.

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)