How to Increase Self-Motivation

The present article reviews effective self-motivation techniques, based on findings cited in a paper by Fishbach, published in the December 2021 issue of Motivation Science.

Self-motivation means being driven by a personal desire to set valued goals and to focus on, commit to, and move toward these goals despite obstacles. Self-motivation is necessary for many situations, especially when what we desire immediately (e.g., eating pizza) is not what we should do (e.g., eating healthy). For instance, we motivate ourselves to do chores, engage in self-care, and better ourselves (e.g., become more conscientious).

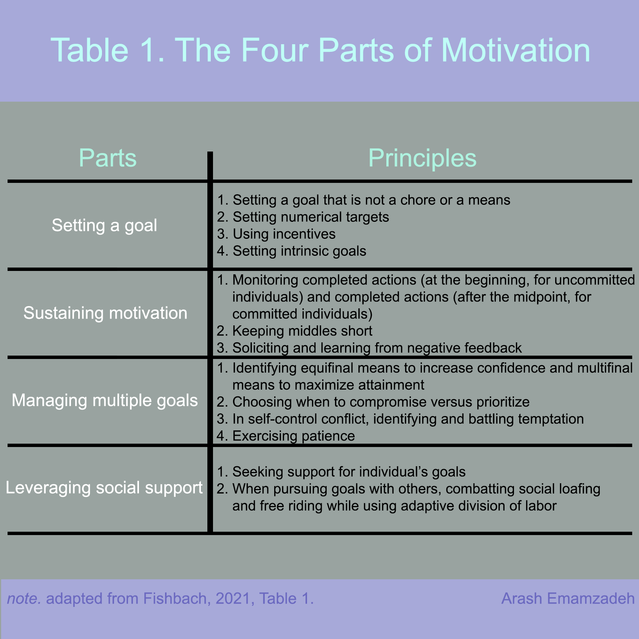

But how do you motivate yourself, exactly? Below, I review effective motivational strategies related to four elements of motivation: goal setting, goal striving, goal juggling, and leveraging social support. See Table 1.

Source: Arash Emamzadeh (adapted from Fishbach et al., 2021)

Mục Lục

Goal Setting

We begin with strategies for successful goal setting.

- Set a goal, not a means to a goal: If goal pursuit does not excite you, you are probably pursuing a means to a goal (e.g., finding a parking spot in a crowded area), not the goal (e.g., buying a special gift for a loved one). So, keep in mind your ultimate destination.

- Set SMART goals: Smart stands for specific, measurable, attainable (i.e. neither too easy nor too difficult), relevant, and time-bound. Instead of saying, “I want to lose weight,” specify how many pounds and in how many months; and how you plan to accomplish your goal. Also, goals should be self-set, not imposed; otherwise, you might rebel against them.

- Set incentives: Incentives are like “mini-goals” and increase motivation. However, they sometimes undermine the original goal (e.g., you study just for the incentive of eating chocolate). Furthermore, uncertain incentives (e.g., 20 or 40 minutes to play video games, randomly chosen) are potentially more motivating than certain ones (always 30 minutes).

- Use intrinsic motivation: To motivate yourself, pursue intrinsically motivating goals—i.e. inherently beneficial and enjoyable activities (e.g., a job you love; an exercise you enjoy) and not a means to another goal (e.g., to lose weight, you jog, but you hate jogging).

Sustaining Motivation

To sustain motivation, monitor your progress.

- Dynamics of goal motivation: To motivate yourself, reflect on your achievements (e.g., good grades; work success). Why? Because they demonstrate commitment to your goal, thus promoting consistency. Alternatively, reflect on things you have not accomplished yet. Why? Because they indicate a lack of progress (e.g., not having completed any extra-credit assignments), thus enhancing motivation to make progress.

- The middle problem: Motivation is usually high initially and toward the end, but not in the middle. The solution? Keep the middles very short (e.g., instead of monthly goals, set weekly goals).

- Learning from negative feedback: People are less likely to learn from negative than positive feedback, perhaps because they take it too personally. The solution? To protect your ego, focus on the lessons learned; sharing these lessons with others, in the form of giving advice, may also protect your ego. Additional techniques include developing a growth mindset, intentionally making minor mistakes (to practice learning from errors), and learning from others’ failures.

Goal Juggling

Rarely do we pursue a single goal, so we must learn to juggle goals.

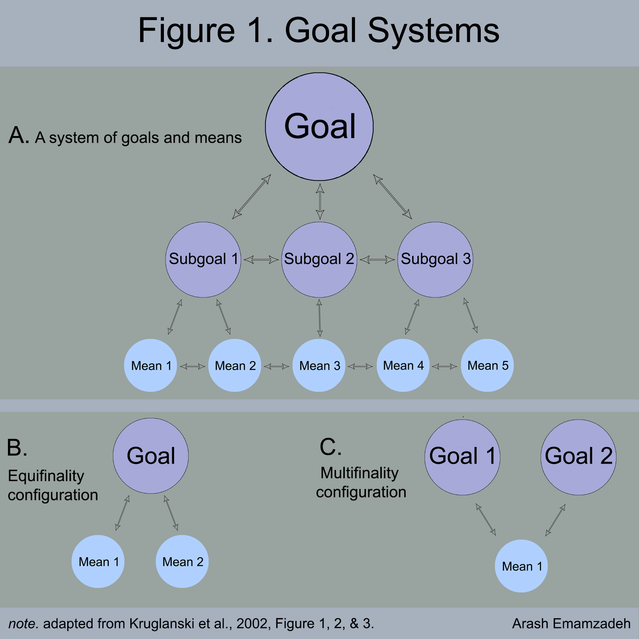

- Complementing goals: To increase goal commitment, select multiple means serving a single goal (e.g., eating healthy and dancing both help you lose weight; Figure 1B). To attain more goals, use means serving multiple goals (e.g., dancing for both weight loss and increased flexibility; Figure 1C). If you lose motivation, go back to performing activities that each serve mainly one goal.

- Compromising vs. prioritizing: To resolve goal conflicts, we prioritize (choose A over B) or compromise (choose the middle ground or a third goal C). Framing an activity as progress encourages compromise but framing it as commitment encourages prioritization (see Point 1 in the section on sustaining motivation). So, be careful how you frame activities.

- Self-control: Successful self-control requires first identifying a conflict. This necessitates examining behavioral patterns. For example, eating two slices of cake in one sitting is not a problem unless done regularly. Second, it requires us to exercise self-control. How? One, by changing the environment (e.g., filling the fridge with healthy food). Two, by changing our perception of a goal’s value (e.g., “I will feel proud of myself if I control my weight”) and reducing the value of the temptation (e.g., “I will feel guilty if I overeat” or “Looking at it closely, this doesn’t look appetizing”).

- Patience: Goal conflicts often involve having to choose between something good soon and something great later (e.g., a yearly vacation vs. buying a house in five years). How to motivate yourself to remain patient? Use distractors, remind yourself of the value of your goal, and trust the process (i.e. “good things happen to those who wait”).

Source: Arash Emamzadeh (adapted from Kruglanski et al. 2002)

Social Support

Social support can increase motivation.

- Leverage social support: The mere presence of people increases motivation, magnifying what you do. Additionally, others may set expectations for performance—though in rare cases, too high of an expectation, which lowers motivation—provide resources, join you (e.g., study groups), and serve as role models.

- Pursuing group goals: When pursuing goals as a group (e.g., be it a husband and wife, a class, or a community), in order to make sure all members are doing their fair share (i.e. to prevent free-riding and social loafing), make contributions public, increase members’ identification with the group, and inspire group members with your contributions. In addition, remember that in many groups, as far as resources are concerned, the goal is not an equal partnership but maximizing benefits for the group as a unit. Naturally, this can be motivating only if the resources you expect to obtain as a group justifies ignoring your personal desires or ambitions (e.g., relocating because of your spouse’s financially rewarding career).

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)