How to Identify New Business Models

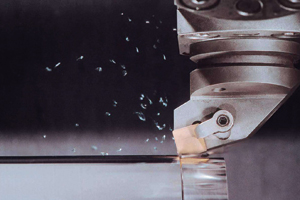

By systematically examining alternative business models, the tool manufacturer Kennametal was able to develop new service-based offerings.

By systematically examining alternative business models, the tool manufacturer Kennametal was able to develop new service-based offerings.

Image courtesy of Kennametal.

Organizations traditionally pursue growth via one or more of three broad paths:

- They invest heavily in product development so they can produce new and better offerings.

- They develop deep consumer insights in order to offer new and better ways to satisfy customers’ needs.

- They concentrate on strategy formulation to grow by acquisition or by moving into new or adjacent markets.

Each of these paths usually involves devoting considerable time and resources to developing a corresponding organizational competency. For example, to build product capability, companies typically invest in in-house research and development departments and/or technology-sourcing expertise. Establishing customer insight capability often requires creating in-house market research units and implementing robust feedback links between the sales force and the developers of product or service lines. And creating a strategy capability generally involves setting up dedicated corporate strategy units and merger and acquisition groups or engaging consultants.

Recently, a fourth path has emerged, one that we might label “business model experimentation”: the pursuit of growth through the methodical examination of alternative business models. At its heart, business model experimentation is a means to explore alternative value creation approaches quickly, inexpensively and, to the extent possible, through “thought experiments.” The process sheds new light on potential competitors and lowers the risk of taking the wrong or a lesser-potential road — all for an initial investment that is typically quite small relative to what can be gained.

Research conducted in the last 10 years has established a link between business model innovation and value creation.1 To our minds, this research points to the need for organizations to build a competency in business model innovation — that is, in the process of exploring possible business model alternatives that can be pursued to commercialize any given idea prior to going out into the market and expending resources. However, few organizations have successfully conceived and executed a business model different from their current one, fewer still have done it more than once and only a handful have put in place a methodical approach to business model innovation.

About the Authors

Joseph V. Sinfield is an associate professor of civil engineering at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, and a senior partner at the innovation and strategy consulting firm Innosight. Edward Calder, a principal at Innosight, is based in the firm’s Lexington, Massachusetts, headquarters. Bernard McCon-nell is vice president of WIDIA Products Group at Kennametal, based in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Steve Colson is a company coach at Open Water Development Ltd. and a former general manager of growth initiatives at petroleum-additive maker Infineum in the United Kingdom.

References

1. See T.W. Malone, P. Weill, R.K. Lai, V.T. D’Ursio, G. Herman, T.G. Apel and S.L. Woerner, “Do Some Business Models Perform Better Than Others? “Working paper 4615-06, MIT Sloan School of Management, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2006) May 16; S.M. Shafer, H.J. Smith and J.C. Linder, “The Power of Business Models,” Business Horizons 48, no. 3, (2005): 199-207; E. Giesen, S.J. Berman, R. Bell and A. Blitz, “Three Ways to Successfully Innovate Your Business Model,” Strategy & Leadership 35, no. 6 (2007): 27-33; and M.W. Johnson, C.M. Christensen and H. Kagermann, “Reinventing Your Business Model,” Harvard Business Review, 86, no. 12 December 2008: 51-59. In a study of 1,000 of the largest U.S. firms, for example, Malone et al. called attention to the link and mapped out a comprehensive classification system that can be employed both to categorize and to develop business models. Shafer et al. described the benefits General Motors gained by employing business model innovation in the development of OnStar, and contrasted this success story with the narrow and less innovative approach employed to define the business model for eToys in the late 1990s. Giesen et al. examined 35 financially successful enterprises and outlined three distinct paths to business model innovation — industry, revenue and enterprise model innovation — that were at the core of their success. Further, Johnson et al. explored the stories of P&G, Tata, Hilti and Dow Corning to emphasize the financial and long-term competitive differentiation benefits that companies can achieve through business model innovation.

2. Johnson et al., “Reinventing Your Business Model.”

3. Shafer et al., “The Power of Business Models”; and M. Morris, M. Schindehutte and J. Allen, “The Entrepreneur’s Business Model: Toward a Unified Perspective,” Journal of Business Research 58, no. 6 (June 2005): 726-735.

4. J.V. Sinfield and S.D. Anthony, “Constraining Innovation: How Developing and Continually Refining Your Organization’s Goals and Bounds Can Help Guide Growth,” Strategy & Innovation 4, no. 6 (November-December 2006): 1, 6-9.

5. For more on conducting research into discovering such needs see, for example, C.M. Christensen and M.E. Raynor, “The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press, 2003); and S.D. Anthony and J.V. Sinfield, “Product for Hire: Master the Innovation Life Cycle With a Jobs-to-be-done Perspective of Markets,” Marketing Management 16, no. 2 (March-April, 2007): 18-24.

Reprint #:

53214

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)