How Healthy Is Your Business Ecosystem?

Paying attention to the right metrics and red flags will help leaders sidestep the most common pitfalls in the four phases of ecosystem development.

Image courtesy of Harry Campbell/theispot.com

Mục Lục

The Research

- The authors built a database of more than 100 failed ecosystems, including B2C, C2C, and B2B platforms; social networks; marketplaces; software solutions; and payment, mobility, entertainment, and health care services.

- They compared the failed ecosystems with their successful counterparts by industry using systematic qualitative and quantitative analysis.

- They studied the development of all the ecosystems and identified key success metrics and red flags that are early indicators of emerging challenges in each of the four life cycle phases.

Companies that start or join successful business ecosystems — dynamic groups of largely independent economic players that work together to create and deliver coherent solutions to customers — can reap tremendous benefits. In the startup phase, ecosystems can provide fast access to external capabilities that may be too expensive or time-consuming to build within a single company. Once launched, ecosystems can scale quickly because their modular structure makes it easy to add partners. Moreover, ecosystems are very flexible and resilient — the model enables high variety, as well as a high capacity to evolve. There is, however, a hidden and inconvenient truth about business ecosystems: Our past research found that less than 15% are sustainable in the long run.1

The seeds of ecosystem failure are planted early. Our new analysis of more than 100 failed ecosystems found that strategic blunders in their design accounted for 6 out of 7 failures. But we also found that it can take years before these design failures become apparent — with all the cumulative investment losses in time, effort, and money that failure implies.2

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Privacy Policy

Witness Google, which made several unsuccessful attempts to establish social networks. It invested eight years in Google+ before shutting down the service in 2019. One reason for the Google+ failure was its asymmetric follow model, similar to Twitter’s, in which users can unilaterally follow others. This created strong initial growth but did not build relationships, which might have fostered greater engagement on the platform. The downfall of another Google social network, Orkut, was built into its unusually open design, which let users know when their profiles were accessed by others. It turned out that users were uncomfortable with this lack of privacy, and the network went offline in 2014, 10 years after its launch.

Typically, ecosystems are assessed using two kinds of metrics: conventional financial metrics, such as revenue, cash burn rate, profitability, and return on investment; and vanity metrics, such as market size and ecosystem activity (number of subscribers, clicks, or social media mentions). The former are not very useful for assessing the prospects of ecosystems because they are backward-looking. The latter can be misleading because they are not necessarily linked to value creation or extraction. They indicate the current interest in the ecosystem, and presumably its potential, but may also reflect an ecosystem’s ability to spend investors’ money on marketing and other growth tactics more than its ability to generate value.

To improve the odds of success and mitigate the high costs of failure, leaders must be able to assess the health of a business ecosystem throughout its life cycle. They need metrics that indicate performance and potential at the system level and at the level of the individual companies or partners participating in the ecosystem, as well as the ecosystem leader or orchestrator. They need to be able to gauge growth in terms of scale not only in ecosystem participation but also in the underlying operating model. And most critically, they need metrics that reflect the success factors unique to each of the distinct phases of ecosystem development.

This article lays out a set of metrics and early warning indicators that can help you determine whether your ecosystem is on track for success and worthy of continued investment in each development phase. They can also help you identify emerging issues and decide if and when you may need to cut your losses in an ecosystem and/or reorient it.

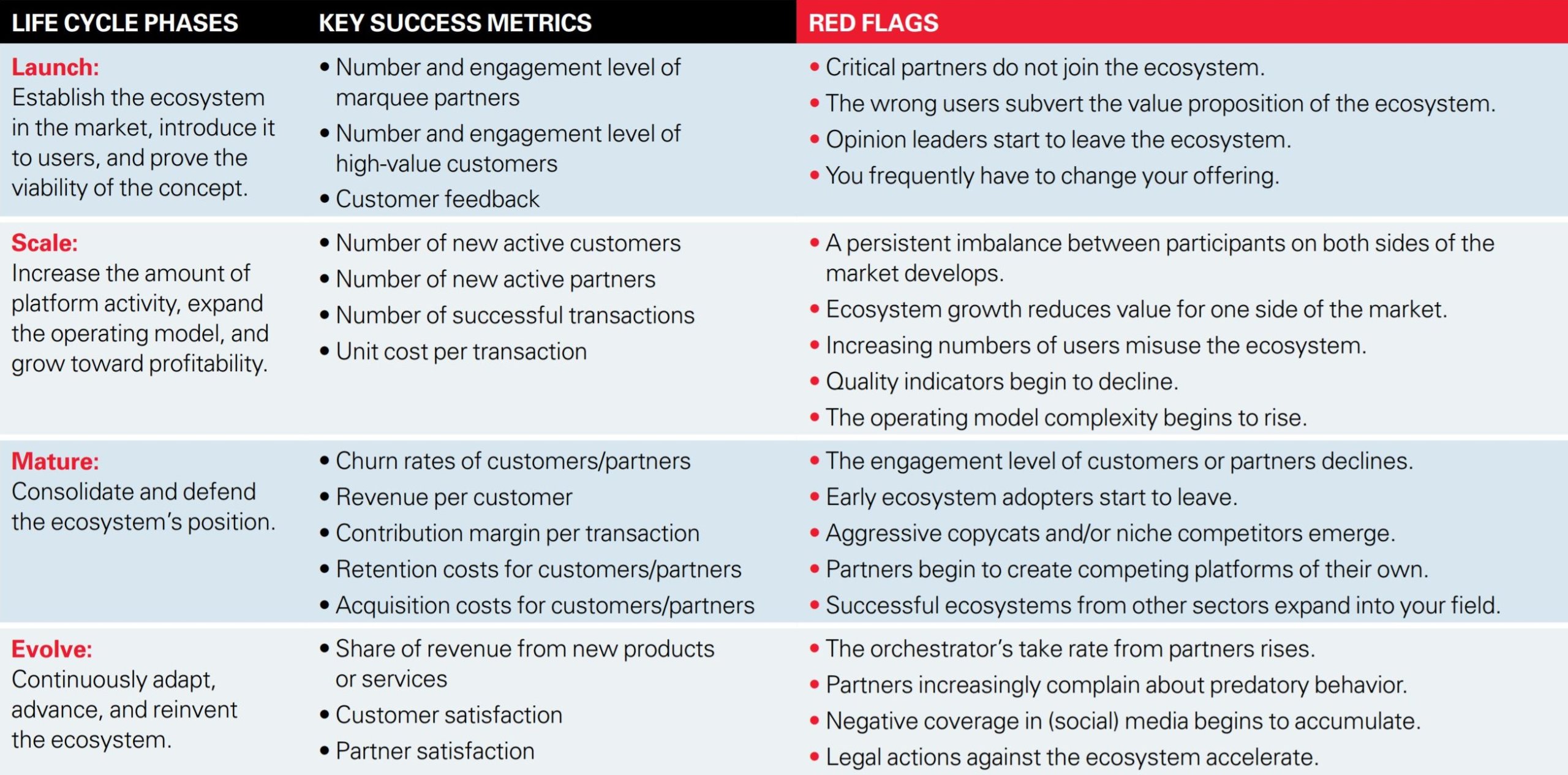

Four Phases in the Business Ecosystem Life Cycle

Our current research revealed that the growth of business ecosystems typically occurs in four phases. Each encompasses unique jobs to be done with corresponding success factors and thus also requires specific indicators and metrics for assessing ecosystem health.

In the launch phase, the focus should be on developing a strong value proposition for all ecosystem participants (the orchestrator, partners, and customers) and on finding the right initial design. After the ecosystem is established, it enters the scale phase, in which the key focus is to increase the number and intensity of interactions in the ecosystem and to decrease the unit cost of each interaction. An ecosystem that has successfully scaled enters the maturity phase, in which growth slows and focus turns to bolstering customer and partner loyalty, and on erecting barriers to entry by competitors. Once a defensible position is attained, the ecosystem enters the evolution phase, in which the focus shifts to expanding the offering and innovating continuously.

To assess ecosystem health in each of these phases, leaders need to ask and answer the following questions:

- What is the definition of success? What are the primary milestones that you need to achieve to master the current life cycle phase and enter into the next phase?

- What do you need to get right? What are the key factors that make the difference between success and failure in this phase?

- What are key success metrics? Which numbers should you track to assess the performance of your ecosystem in this phase?

- What are red flags? What are early warning indicators that signal that your ecosystem may not be on the path to success, that you may have to change your initial design, or that you should shut it down?

How to Track Ecosystem Health Through Its Life Cycle

Life Cycle Phases

Key Success Metrics

Red Flags

Launch:Establish the ecosystem in the market, introduce it to users, and prove the viability of the concept.

• Number and engagement level of marquee partners

• Number and engagement level of high-value customers

• Customer feedback

• Critical partners do not join the ecosystem.

• The wrong users subvert the value proposition of the ecosystem.

• Opinion leaders start to leave the ecosystem.

• You frequently have to change your offering.

Scale: Increase the amount of platform activity, expand the operating model, and grow toward profitability.

• Number of new active customers

• Number of new active partners

• Number of successful transactions

• Unit cost per transaction

• A persistent imbalance between participants on both sides of the market develops.

• Ecosystem growth reduces value for one side of the market.

• Increasing numbers of users misuse the ecosystem.

• Quality indicators begin to decline.

• The operating model complexity begins to rise.

Mature: Consolidate and defend the ecosystem’s position.

• Churn rates of customers/partners

• Revenue per customer

• Contribution margin per transaction

• Retention costs for customers/partners

• Acquisition costs for customers/partners

• The engagement level of customers or partners declines.

• Early ecosystem adopters start to leave.

• Aggressive copycats and/or niche competitors emerge.

• Partners begin to create competing platforms of their own.

• Successful ecosystems from other sectors expand into your field.

Evolve: Continuously adapt, advance, and reinvent the ecosystem.

• Share of revenue from new products or services

• Customer satisfaction

• Partner satisfaction

• The orchestrator’s take rate from partners rises.

• Partners increasingly complain about predatory behavior.

• Negative coverage in (social) media begins to accumulate.

• Legal actions against the ecosystem accelerate.

Phase 1: Launch

The goal in the launch phase is to establish the ecosystem in the market by introducing it to users and proving the viability of the concept. To this end, the orchestrator needs to formulate the value proposition and delineate the initial structure of the ecosystem. This work includes defining the activities and partners needed to deliver the value proposition, the links among them, the roles and responsibilities of the different participants, and the design of the governance and operating models. We identified four key factors that make the difference between success and failure during the launch phase.

First, the profit potential of the ecosystem must be large enough to justify the investment required to establish it and attract the partners needed to operate it. This ultimately depends on the value that the ecosystem can create for its customers and their willingness to pay for it. To achieve this, the ecosystem must, for example, remove a substantial source of friction for customers or fulfill a sizable unmet or new customer need.

Second, the orchestrator must motivate the required participants to commit and contribute to the ecosystem. This is about not only the sheer number of participants but also the right participants (such as popular developers on a gaming platform) in the right proportions (a balanced number of drivers and riders on a ride-hailing platform, for example).

Third, the orchestrator must determine the proper level of openness for the ecosystem and create the standards, rules, and processes to regulate access and decision rights. Open ecosystems usually experience faster growth, particularly during the launch phase. They enable greater diversity and encourage decentralized innovation. Closed ecosystems allow for a more deliberate design of the ecosystem and for greater control over business partners and the quality of offerings.

Finally, the orchestrator must decide how to charge for the ecosystem’s products and services, and determine how to share the value created in ways that motivate participants to foster ecosystem growth.

Metrics: Many metrics can be tracked during the launch phase of your ecosystem, including marketing expenses, technology costs, revenues, funding, burn rate, total number of users, and media attention. But to assess ecosystem health during this phase and evaluate the odds of success, we suggest focusing on the following three key metrics:

- Number and engagement level of marquee suppliers. For example, a restaurant booking platform would want to track the number of subscriptions and reservations among the leading restaurants in key cities.

- Number and engagement level of high-value customers. For a gaming platform, this might be heavy users who buy add-ons to enhance play; for a B2B marketplace, it might be the largest companies in target sectors; and for a social media platform, it might be prominent opinion leaders.

- Customer feedback. This is measured based on quality ratings of the ecosystem’s products and services in comparison to competing offerings, or Net Promoter Scores in customer surveys. In this case, aggregated metrics should be augmented with qualitative feedback from individual customers to understand the root causes of customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

Red flags: If your scores on these three metrics are strong and trending higher, it is likely that your ecosystem is performing well in the launch phase. If, however, any of the following red flags appear, your ecosystem may be veering off the path to success, and you may have to change your initial design or shut down altogether:

- Critical partners do not join the ecosystem. Better Place was founded in 2007 to provide an infrastructure for the efficient charging or exchange of electric car batteries. In this model, a buyer purchased a vehicle without a battery and paid a mileage-based monthly fee for leasing, charging, and exchanging it. Better Place failed in 2013, after receiving more than $900 million in funding, because it was unable to secure the participation of automakers, an essential group of partners in the ecosystem.3

- The wrong users subvert the value proposition of the ecosystem. YouTube was set up as a platform for people to share personal videos, but in its early years many people used the platform to post illegally copied content. As a result, YouTube was sued by several record labels for billions of dollars, and it had to install a strong copyright identification system and monetization options for copyright holders.4

- Opinion leaders begin to leave the ecosystem. In the DVD player war that started in 2005, the HD DVD platform, developed by Toshiba, Microsoft, and others, initially sold more players than the Blu-ray platform, championed by Sony and Apple. However, the HD DVD camp had to concede defeat after large film studios, including Warner Brothers and Fox Searchlight Pictures, defected to Blu-ray.5

- The ecosystem’s value proposition is changed frequently. Frequent changes to the value proposition suggest that it is not sufficiently compelling or that it appeals to too few customers. Club Nexus, created at Stanford in 2001, was the first college-specific social network. It reached 1,500 members within six weeks of its launch, but growth leveled off just as quickly. The network responded by adding new features, such as chat, email, classified ads, articles, and events. However, the added complexity only made the platform more difficult to use, and the network soon closed down.6

Phase 2: Scale

When ecosystems survive the launch phase, the focus of orchestrators shifts toward increasing the amount of platform activity, scaling the operating model, and growing toward profitability. Two key factors determine the difference between success and failure during this phase.

The first factor is the ability to establish and harness strong positive network effects that provide demand-side economies of scale. Direct network effects occur when the value derived by users on one side of an ecosystem grows as their numbers increase (such as social network users). Indirect network effects manifest when the value derived by participants on one side of an ecosystem grows with the number of participants on another side (for example, drivers on a ride-hailing platform prosper as the number of riders increases).

The second success factor is the ability of the ecosystem’s operating model to keep up with growing demand and realize economies of scale. Successful digital ecosystems benefit from asset-light business models, low-to-zero marginal costs, and increasing returns. However, the economies afforded by supply-side scale can be limited by rising marketing, recruiting, and technology expenses. As networks grow, increased complexity and quality control can drive up costs and diminish economies of scale, too.

Metrics: To assess the extent to which your ecosystem is fulfilling these success factors during the scale phase, we suggest that you focus on the following four key metrics:

- Number of new active customers. Rapidly attracting new active customers to the ecosystem is the key to achieving scale on the demand side.

- Number of new active partners. Increasing the scope, diversity, and scale of the offering is an important precondition for appealing to new customer segments.

- Number of successful transactions. Increasing the number of transactions is crucial because ecosystems create value for customers, partners, and orchestrators through transactions, not through media attention, number of registered users, or click rates.

- Unit cost. Unit cost — that is, the average total ecosystem cost per transaction — must decrease during the scale phase in order for ecosystem growth to provide value for all participants.

Red flags: In addition to these metrics, a number of early warning signs may indicate that your ecosystem is not on track during the scale phase and that you need to adjust its design or governance model:

- A persistent imbalance develops between the number of participants on different sides of the market. U.S. fleet-card companies, such as Comdata (now owned by FleetCor Technologies) and Wex, sought to orchestrate ecosystems that cut maintenance and administrative costs for the owners of truck fleets and drove business to truck stops. But they found it hard to scale initially because they could not convince enough fleet operators to pay for the service. To resolve the imbalance and attain profitable scale, the orchestrators changed their pricing structure from one in which truck fleets paid and truck stops were subsidized to one in which truck stops contributed considerably more to revenues than fleets.7

- Ecosystem growth reduces value for one side of the market. Covisint, an auction marketplace in which automotive suppliers bid for contracts from car manufacturers, quickly attracted $500 million in funding from five major automakers. But as the ecosystem reached the scale phase, it became increasingly unattractive for suppliers: As more of them joined the ecosystem, the competition for contracts led to lower and lower winning bids. Suppliers abandoned the platform, and in 2004 it was sold for just $7 million.8

- Increasing numbers of users misuse the ecosystem. As OpenTable, the restaurant booking platform, scaled, the incidence of no-show reservations grew along with it, alienating its restaurant partners. To mollify them, the platform introduced a policy that banned users who failed to show up or canceled reservations less than 30 minutes in advance four times within a 12-month period.9

- Quality indicators begin to decline. If the quality of an ecosystem’s offerings deteriorates during the scale phase, a downward spiral in both supply and demand can develop. For example, social media platform MySpace did not require users to provide their real identity. As a result, the platform became littered with spam and attracted inappropriate content, which, in turn, made it less attractive for major brands to be associated with the ecosystem and ultimately contributed to its demise.10

- Operating model complexity begins to rise. In the early days of the internet, Yahoo became a leading internet portal and search engine by manually curating and categorizing websites into topic areas. This operating model worked well until the internet started to grow exponentially and the number of websites exploded. It quickly became apparent that Yahoo’s model was not scalable, and it was overtaken by Google and its automatic page-rank algorithm.11

Phase 3: Maturity

In the maturity phase, the growth of the ecosystem begins to slow because its market is increasingly saturated and it has captured a substantial share. Now, management’s primary objective shifts to consolidating and defending the ecosystem’s position. This can be challenging because competitive attacks can target either the demand or the supply side of the ecosystem. Moreover, mature ecosystems must avoid complacency and continue being the technology and innovation leaders in their industries. Two key factors make the difference between success and failure during the maturity phase.

First, the orchestrator needs to find ways to enhance the loyalty of ecosystem participants, because competitors will increasingly try to poach them. This is a particularly dangerous threat when ecosystem participants can simultaneously join multiple competing ecosystems and/or easily switch between ecosystems. For example, restaurants and consumers often use more than one food-delivery platform. To reduce this risk, orchestrators can offer additional services to participants and add user incentives, such as loyalty programs.

Second, orchestrators of mature ecosystems must erect barriers to entry to defend their positions against incursions by competitors and imitators. Digital ecosystems require lower initial investments, and their network effects are weaker and can be more easily reversed than the physical network effects of, say, a railroad or telephone network. To build barriers to entry, orchestrators can harness network, scale, and learning effects (such as using customer data and advanced analytics to continuously improve and personalize offerings) that are difficult for new entrants to match.

Metrics: To assess ecosystem health during the maturity phase, orchestrators and partners should focus on the following five metrics:

- Churn rates of customers and partners. Churn rates, the annual percentage rates at which customers stop using an offering or partners stop contributing to the ecosystem, are the most direct measures of loyalty and performance vis-à-vis competing ecosystems.

- Revenue per customer. This metric quantifies users’ engagement levels and loyalty. Increasing revenue per customer is an important growth lever after a high level of market penetration is achieved.

- Contribution margin per transaction. This metric reflects the value that consumers assign to the transactions within the ecosystem. Declining contribution margins per transaction indicate increasing price pressure and competitive intensity.

- Retention costs for customers and suppliers. Frequently, retention costs are treated as a fixed cost or not explicitly measured at all, but they can undermine the economics of the ecosystem if they continuously escalate.

- Acquisition costs for customers and partners. Similar to retention costs, acquisition costs are frequently not broken out separately, but they are also potentially detrimental to ecosystem economics.

Red flags: A number of early warning signs can help you recognize if your ecosystem is not on track during the maturity phase and when you need to take action:

- The engagement level of customers or partners declines. Declining levels of engagement among ecosystem participants often presage revenue declines. The demise of MySpace was foretold when the frequency of use began falling (with only 3% of users checking the app multiple times daily), while more than 30% of users of emerging competitor Facebook checked that app multiple times per day. This was at least partially caused by design choices: MySpace was profile-based, and most profiles were static; Facebook was feed-based and constantly delivered new content to users.12

- Early ecosystem adopters begin to leave. Early adopters are always in search of the most exciting and advanced offering in a given domain. If they are leaving your ecosystem, there is a good chance that a serious competitor has emerged. At the time of this writing, Twitch is the dominant platform for livestreaming online video games; it had a 73% market share at the end of 2019.13 However, some of its key early adopters are switching to competing platform YouTube. For instance, Activision Blizzard announced a multiyear exclusivity deal with YouTube in January 2020, which means that Twitch has lost what was at one time its second-most-watched gaming channel, Overwatch League. In addition, a few high-profile gamers with millions of followers have switched from Twitch to YouTube.14

- Aggressive copycats and/or niche competitors emerge. Successful business models attract competition from me-too players that offer a similar value proposition at a lower price and from niche competitors that bring specialized offerings to specific segments of the market. For example, Upwork, the leading marketplace for freelance labor, faces competition from hundreds of niche platforms that focus on specific industries, job types, and locations.

- Ecosystem partners begin to create competing platforms of their own. Sometimes partners in successful ecosystems decide to become orchestrators of their own ecosystem. Handset maker Samsung, for example, is a partner in Google’s Android ecosystem but has developed its own app store, the Samsung Galaxy Store, that is in direct competition with the Google Play Store.

- Successful ecosystems from other sectors launch competitive thrusts. Ecosystem carryover — the expansion of a successful business ecosystem into a neighboring domain — is an important route for ecosystem growth and expansion, but it is also a substantial threat for incumbent ecosystems. For example, the credit card ecosystems orchestrated by Visa and Mastercard are under pressure from retail marketplaces that are moving into payment services.

Phase 4: Evolution

When ecosystems master the maturity phase, they shift their focus to continuously adapting, advancing, and reinventing themselves before their competitors do. According to our research, three key factors explain most of the difference between success and failure during the evolution phase.

First, ecosystem success over the long term depends on the ability to both learn and innovate faster than competitors. The exact evolution of a business ecosystem cannot and should not be planned in advance. Instead, a key strength of the model is its responsiveness to customer needs and technological changes. To support this, orchestrators must be open to the creativity of ecosystem participants and build flexibility and adaptability into their platforms.

Second, sustainable ecosystems find ways to expand their value propositions. This expansion can stem from the addition of new products or services to an existing ecosystem (such as LinkedIn’s addition of online recruiting and content publishing services), expanding into adjacent markets (such as the expansion of ride-hailing platforms into food delivery), or full ecosystem carryovers (such as Apple leveraging its strong position in the music player ecosystem to conquer the smartphone ecosystem).

Third, as the ecosystem expands, risk management strategies become increasingly important. Dominant ecosystems may have significant negative impacts on internal and external stakeholders, who will naturally push back. Such pushback can come from incumbents (local taxi companies that fight Uber), partners (who complain about unfair pricing on the Amazon marketplace), users (who criticize Facebook’s data privacy policies), or regulators (the European Union, which fined Google for anticompetitive behavior in the Android ecosystem). Ecosystems that succeed over the long term avoid predatory behavior, ensure fair value distribution among all relevant stakeholders, and proactively manage stakeholder perceptions.

Metrics: In addition to the health metrics for the maturity phase, which continue to be highly relevant, ecosystems should focus on three additional key metrics during the evolution phase:

- Share of revenue from new products or services. The revenue derived from new additions to the ecosystem are a direct measure of ability to innovate and of progress in expanding the offering.

- Customer satisfaction. This is a defensive measure that not only alerts orchestrators if their ecosystem is losing its edge but also reflects the quality of the expanded offering. As in the launch phase, aggregated measures of customer satisfaction should be complemented by one-on-one conversations and qualitative feedback.

- Partner satisfaction. This measures the extent to which partners feel they are treated fairly and are loyal to the ecosystem, and it reflects the new business opportunities provided by the expanding ecosystem. Again, it is important to listen carefully to qualitative feedback from partners and to act on what you hear.

Red flags: A number of early warning signs may indicate that your ecosystem is not on track during the evolution phase and that you need to adjust your development path or behavior:

- The orchestrator’s take rate from partners rises substantially. Rising take rates can significantly alter partner economics and may encourage partners to leave the ecosystem. They can also indicate that the orchestrator is more focused on extracting value from the ecosystem than on growing it and creating attractive new opportunities. For example, Etsy, which offers a marketplace for craftspeople and artists, recently raised its take rate from 3.5% to 5%, forced its partners to use its internal payment platform, and required participation in a program that charges an additional 12% to 15% on sales resulting from Etsy ad click-throughs. While Etsy continues to do well, this alienated many partners, leading some of them to protest and leave the platform.15

- Partners increasingly complain about predatory behavior. Successful orchestrators can be tempted to exploit their dominant position and impose unfair terms and conditions on the ecosystem. Take, for example, EU regulators’ investigation into Amazon’s marketplace practices and its dual position as both retailer and platform. That scrutiny was spurred by critics’ accusations that Amazon used sales data from its third-party merchants to launch its own competing product lines and unfairly promoted its own brands.16 Perceptions of predatory behavior create opportunities for competing ecosystems to attract important partners.

- Negative coverage in (social) media begins to accumulate. Network effects cut both ways. When negative comments accumulate, they can become amplified and lead to a downward spiral that threatens the viability of an ecosystem. This is what happened to MonkeyParking, a platform that enabled drivers to auction vacated public parking spaces to other drivers. After being broadly criticized for privatizing and monetizing a public good, MonkeyParking pivoted into a platform that helps owners of parking spaces rent them.17

- Legal actions against the ecosystem accelerate. Napster, a peer-to-peer file-sharing website, didn’t check the copyright status of files that were shared on its platform, leading many people to use it for illegal music sharing. At its peak, Napster had 80 million registered users, but too many of them illegally shared copyrighted content. As a result, Napster was sued by several record labels and popular musicians, such as Metallica and Dr. Dre. In 2001, it was forced to shut down after losing a major lawsuit. The company tried, but failed, to relaunch with appropriate copyright filters, and eventually its name was sold and used to rebrand an online music store.18

Conducting an Ecosystem Health Assessment

The odds are against ecosystem success, but if you are an orchestrator or a partner, you can improve your odds by using the metrics and red flags described above. To be successful, you should recognize that different phases of ecosystem development require very different managerial focal points and explicitly adopt new metrics as needed.

Related Articles

Incorporate the metrics into your management information system and discuss them and the red flags in your strategy reviews. If you find that your ecosystem is performing weakly on one or more metrics or experiencing the red flags, seek to identify the underlying drivers so that you can address them and prevent future damage.

Be open to failure and have a clear pivot or exit plan. Given the hard reality that 85% of ecosystems fail to achieve long-term sustainability, the ecosystem you initially aim to set up or join will most likely not succeed. This means that it is critical to have clear targets and plans for when and how to change course.

The metrics and red flags described above aren’t the only metrics needed to assess a business, but they can help you track the key drivers of ecosystem health and ensure that your company beats the odds and succeeds.

About the Authors

Ulrich Pidun is a partner and director at Boston Consulting Group and a fellow at the BCG Henderson Institute. Martin Reeves (@martinkreeves) is a senior partner at Boston Consulting Group and chairman of the BCG Henderson Institute. Edzard Wesselink is a principal at Boston Consulting Group and an ambassador at the BCG Henderson Institute.

References

1. M. Reeves, H. Lotan, J. Legrand, et al., “How Business Ecosystems Rise (and Often Fall),” MIT Sloan Management Review, July 30, 2019, https://sloanreview.mit.edu.

2. U. Pidun, M. Reeves, and M. Schüssler, “Why Do Most Business Ecosystems Fail?” Boston Consulting Group, June 22, 2020, www.bcg.com.

3. R. Adner, “The Wide Lens: A New Strategy for Innovation” (New York: Penguin/Portfolio, 2012).

4. B. Popper, “YouTube to the Music Industry: Here’s the Money,” The Verge, July 13, 2016, www.theverge.com.

5. Y. Kageyama, “Toshiba Quits HD DVD Business,” Los Angeles Times, Feb. 19, 2008.

6. D. Kirkpatrick, “The Facebook Effect: The Inside Story of the Company That Is Connecting the World” (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010).

7. D.S. Evans and R. Schmalensee, “Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms” (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2016).

8. “Covisint Price Tag: $7 Million,” aftermarketNews, June 10, 2004, www.aftermarketnews.com.

9. J. Phillips, “OpenTable Launches New Campaign to Combat Reservation No-Shows,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 21, 2017, www.sfchronicle.com.

10. F. Gillette, “The Rise and Inglorious Fall of MySpace,” Bloomberg Businessweek, June 22, 2011, www.bloomberg.com.

11. G. Press, “Why Yahoo Lost and Google Won,” Forbes, July 26, 2016, www.forbes.com.

12. Kirkpatrick, “The Facebook Effect.”

13. A. Yosilewitz, “State of the Stream 2019: Platform Wars, the New King of Streaming, Most Watched Game and More!” StreamElements Blog, Dec. 19, 2019, https://blog.streamelements.com.

14. A. Khalid, “YouTube Is Now the Biggest Threat to Twitch,” Quartz, Jan. 28, 2020, https://qz.com.

15. L. Debter, “Etsy’s Push to Compete With Amazon Leaves Sellers Squeezed by Rising Costs,” Forbes, Feb. 27, 2020, www.forbes.com.

16. K. Cox, “Antitrust 101: Why Everyone Is Probing Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google,” Ars Technica, Nov. 5, 2019, https://arstechnica.com.

17. T.S. Perry, “Drawing the Line Between ‘Peer-to-Peer’ and ‘Jerk’ Technology,” IEEE Spectrum, July 18, 2014, https://spectrum.ieee.org.

18. M. Harris, “The History of Napster: How the Brand Has Changed Over the Years,” Lifewire, Nov. 18, 2019, www.lifewire.com.

Reprint #:

62307

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)