How countries gamed the World Bank’s business rankings

The World Bank announced in September that it would discontinue its ‘Doing Business’ reports after data irregularities were uncovered. André Broome analyses why the reports were discredited and explains how countries have ‘gamed’ the Ease of Doing Business rankings since they were first introduced in 2005.

In August 2020 the World Bank announced that the publication of its flagship Doing Business reports had been suspended. Internal concerns about possible data manipulation were raised by World Bank staff in June 2020 in connection with the calculation of country scores for Azerbaijan, China, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Published annually since 2003 with country rankings introduced in 2005, the Doing Business reports were a high-profile and influential global benchmark aimed at “measuring the regulations that enhance business activity and those that constrain it”.

A subsequent investigation commissioned by the World Bank’s Board of Executive Directors from international law firm WilmerHale revealed a series of problems with the reliability of the methodology and calculations. It strongly criticised actions taken by Simeon Djankov – one of the three founders of the Doing Business project – in the compilation of data for Doing Business 2020.

In September 2021 the management of the World Bank announced the controversial Doing Business reports would be discontinued due to widely publicised “data irregularities” and “ethical concerns” about the behaviour of some officials, with the Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, Kristalina Georgieva, also accused of rigging the data to boost China’s ranking during her tenure as Chief Executive Officer of the World Bank. While Georgieva was subsequently cleared by the IMF Executive Board of playing an “improper role” in the Doing Business reports, questions about the integrity of the World Bank’s data continue to linger.

What is a benchmark?

Benchmarking is a technique of comparative assessment. Global benchmarking has become increasingly popular for evaluating the quality of countries’ policies and outcomes in specific issue areas, with over 250 global benchmarks introduced since 2000. Key to their appeal is the ability to represent a simplified measure of relative national performance expressed as a numerical ranking or rating.

In contrast to direct forms of global governance, such as policy conditionality in International Monetary Fund and World Bank loans, benchmarking is a mechanism of indirect power that operates at a distance to exert pressure on national policymakers. Drawing on their reputation for expertise and impartiality, intergovernmental organisations have increasingly used benchmarks in an effort to ‘depoliticise’ controversial policy issues, but this only conceals the conceptual biases built into indicators of national economic and social performance, it does not remove them. Benchmarks that rank countries in a hierarchy compound the underlying problems that come with using indicators of national performance as tools of global governance.

Gaming the Ease of Doing Business rankings

The complete list of country rankings originally published by the World Bank (not revised to correct for data irregularities) is available in a new Doing Business Rankings Dataset published in the Harvard Dataverse. This reveals the extent to which the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rankings were characterised by high variability from one year to the next. Over the fifteen years in which they were issued, 111 countries received a spread between their highest and lowest rankings of more than 40 places (out of 190 countries included in the rankings) while 35 countries received a spread between their high/low rankings of 75 places or more.

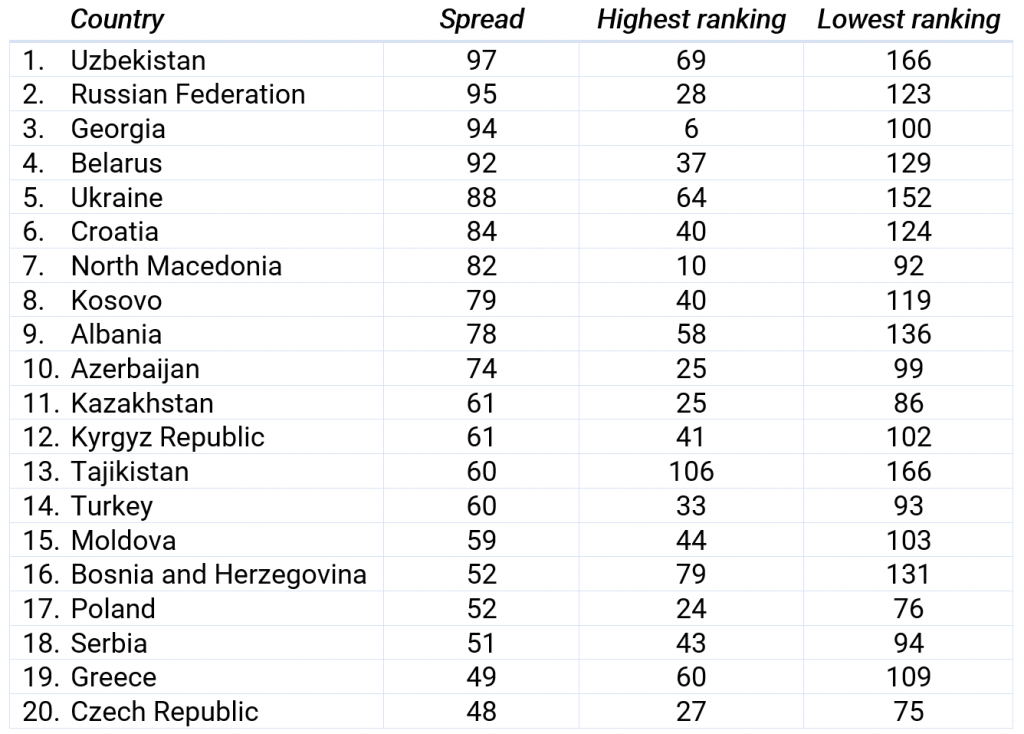

In Europe and Central Asia, many countries experienced significant variability in their rankings over time. Table 1 shows the 20 European and Central Asian countries with the largest spread between their highest (best) and lowest (worst) rankings from the first Ease of Doing Business rankings published in 2005 (Doing Business 2006) to the final rankings published in 2019 (Doing Business 2020).

Table 1: Countries in Europe and Central Asia with the largest spread between highest and lowest rankings in the World Bank’s Doing Business reports

Source: Doing Business Rankings Dataset, available in the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi-org/10.7910/DVN/UVSSNN

There are three main reasons why country rankings in the Doing Business report were subject to high variability over time. First, the World Bank made regular changes to the methodology on which the rankings are based. With the introduction of “distance to frontier” scores in 2015, for example, the methodology was changed for 9 of the 10 indicator categories used to calculate country scores.

Second, the rankings were an attempt to measure evolving systems of regulation and administration, like taking an annual photograph of a moving object. Third, many countries made coordinated attempts to devise and implement policy changes that would improve their future ranking. The World Bank claims that over 70 countries formed regulatory reform committees that were oriented toward the Doing Business indicators.

Consultants as knowledge brokers

While some countries implemented reforms captured by the rankings based on internal government expertise, other countries turned to private consultancies for advice on how regulatory changes could boost their ranking in future Doing Business reports. Aid donors such as the US Agency for International Development (USAID) sponsored numerous multi-year reform programmes, whereby consultancies were contracted by USAID to implement “business enabling environment” projects in developing countries. Such projects often used the Ease of Doing Business rankings to diagnose regulatory problems, construct policy solutions, and evaluate project impact through changes in country rankings.

Much of the media attention on the World Bank’s rankings scandal has focused on two aspects. First, how countries sought to pressure officials to influence the calculation of scores. Second, the conflict of interest highlighted by the WilmerHale report between the World Bank’s Reimbursable Advisory Services contracts (where countries pay for specialised World Bank advice and analysis) and its impartiality as an evaluator of national performance through the Doing Business project.

The knowledge broker role played by private consultancy contractors has not featured in the recent scandal. Yet consultancies have been extensively involved in advising developing countries on business regulation reforms targeted at improving their scores in World Bank rankings. At least 9 of the 20 countries listed in Table 1 above received business enabling environment project funding from USAID between 2005 and 2019, totalling over US$100 million.

Implemented by for-profit consultancy firms, these projects correlated with significant boosts in rankings for Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Serbia, and Ukraine. In Kosovo, for example, consultancy Chemonics International (the third-largest recipient of USAID funding after the World Bank and the United Nations) ran two consecutive USAID projects between 2010 and 2018, which targeted a top-40 position in the Ease of Doing Business rankings as a core objective (achieved in Doing Business 2018).

Replacing the Doing Business reports

The future of global benchmarking by the World Bank to measure the comparative quality of business regulations is now unclear. The World Bank Group’s Chief Economist and new Senior Vice President, Carmen Reinhart, recently announced the organisation intends to replace the Doing Business report within two years. With the focus on “restoring credibility”, Reinhart suggests a replacement business climate benchmark will be more transparent in its methodology and have “less focus on ranking countries”, which she acknowledges incentivised countries to “game the system”.

The problems inherent in the Ease of Doing Business rankings were also part of the secret of their success. It was the simplicity of the country rankings and the stigma attached to a poor position that helped to make the Doing Business reports so influential. Reducing the focus on ranking may well reduce the traction a replacement benchmark is able to achieve. Meanwhile, greater disclosure of the methodology used could prove invaluable to firms in the development consultancy industry, providing new performance measures to stimulate demand among government clients for their advisory services.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: World Bank Photo Collection (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)