Flax – the enduring fibre

Peter Quinn

Society

Flax – the enduring fibre

With lofty flower stalks that stab the sky and leaves as broad as a waka paddle, flax, or harakeke, is one of our most striking native plants—a feature of wetland, coastline and hill country. It has also played a pivotal role in the development of New Zealand’s human landscape.

Written by Gerard Hindmarsh

Photographed by Peter James Quinn

Rock climbers edging up the limestone bluffs at Payne’s Ford Scenic Reserve in Golden Bay get the best view of the flax plantation growing here beside the Takaka River. But I have elected to wander among the bushes at ground level to see what I can learn about one of this country’s most important native flowering plants. There are around 60 varieties in this planting. Some have drooping, floppy leaves; others grow as stiff and upright as spears. To the touch, they vary from a silky fineness to a texture that is waxy and coarse. When their flower stalks are included, the tallest reach to over four metres, although others are only half that size.

At first glance, they seem to be mostly shades of green on green, but a closer look reveals subtle variations. Leaf margins range from orange to deep purple, even black, and the keel running up the centre of each leaf may be yellow, bronze or red. The basic colour of the blades can have the blue tinge of driftwood smoke through to the spring green of pohutukawa. A few plants are strongly variegated, erupting streaks of crimson and sulphur yellow.

The tips of the leaves vary, too. In some plants the leaves taper very gradually to the sharpest of dagger points. In others they are blunt, like a trowel. I notice that the leaves of most types have split back along the midrib for 20 or 30 cm, to give a flat leaf with a gape or open notch at its end, but in a few varieties the two halves hold together, causing the tip to pucker into a shallow skiff.

The plants at Payne’s Ford are all traditional Maori cultivars, selected for propagation on the basis of strength, softness, durability, colour and fibre content. Flax—harakeke—was the fibre of Aotearoa before Europeans arrived with their fancy textiles. When they did, traditional use of harakeke plummeted almost overnight. Flax couldn’t compete with the warmth of wool, the versatility of cotton and the durability of hide.

Perhaps convenience—the fast-food factor—was the main attraction. Pakeha materials came as cloth or finished clothing. Making a garment from scratch out of flax was a lot of work. It could take months for something elaborate. As a result, the mass-produced woollen blanket supplanted the hand-woven fibre cloak in the Maori wardrobe. Harakeke fell from grace, its special cultivars largely neglected.

Today, then, it is indeed a wonder that each clump here before me is labelled with a stout stick inscribed with a traditional name: Matawai, Taniwha, Takaiapu, Makaweroa, Pango, Motu-o-nui, and all the rest. For someone who came thinking one flax is much like any other, it is a revelation.

This particular plot, still tended by local enthusiasts 10 years on from transplanting, is one of half a dozen replications nationwide of what is known as the Orchiston Collection—flax plants originally gathered from the East Coast, Waikato and Taranaki areas of the North Island and planted in a small paddock on a family farm at Hexton, near Gisborne.

The collection is named for Rene Orchiston, who, as a young woman, became fascinated by the flax-working skills shown by local Maori weavers. Now a sprightly octogenarian, she recently left her beloved harakeke bushes behind and moved to a smaller home in Gisborne, but she can still vividly recall how her enthusiasm for flax developed so many years ago.

“It wasn’t so much the process of weaving that used to excite me, rather all the different qualities of flax fibres they produced. The more I delved into it, the more I realised that many fine craftswomen were using inferior materials because of an extreme shortage of specialised cultivars from which to extract good fibre.”

Orchiston was also concerned by the general lack of interest shown in many aspects of Maori culture, including flax weaving, particularly amongst young and middle-aged Maori at that time. “Special flax bushes had been totally neglected—just left to die out in many areas. I could see that in years to come there might be a revival of interest in traditional arts and crafts. Saving as many of those special flaxes as I could became my passion.”

Over the next 30 years, Orchiston crisscrossed the North Island, visiting old settlement sites and marae, gathering information from elderly weavers—especially the original Maori name and use of each flax variety. She willingly swapped plants from a selection which she carried in the boot of her car for this purpose.

“A typical marae had close access to only two or three different types. I’d trade them a flax variety that was, say, much more suited to fine kete [kit] making than the material they were using, and they’d give me one of their local varieties which was ideal for cloak making. In this way I built up my collection, and then I in turn donated thousands of these plants to marae, schools and botanical gardens throughout New Zealand.”

Every one of Orchiston’s flaxes has a personal story: where it grew, who donated it and the story that accompanied it. Sometimes plants were rescued from near-certain oblivion. While searching in the East Coast high country, Orchiston came across an old Maori camp. Nearby were three battered clumps of harakeke, all different—a sure sign of a pa harakeke, or flax plantation. Pig rooting had damaged the plants, so she carefully replanted them after taking a small fan from one, a cultivar she had never seen before. Its straight green blades were unevenly striped with white. The variety was later identified by a Whakatane woman as Motu-o-nui. The other two Orchiston already knew: the short-leafed Oue and the yellow-striped Parekoretawa.

“Harakeke was not indigenous to that particular area, so I knew the flax bushes had to be of high quality, since they must have been carried there on the backs of travellers.”

For many years Rene Orchiston’s work was known only to a small circle of weaving enthusiasts. When the former Department of Scientific and Industrial Research started a small ethnobotany project in 1986, one of its first jobs was to send out husband and wife botanists Geoff Walls and Sue Scheele to identify and rescue as many traditional Maori flaxes as they could find. Imagine their delight when they first drove up the long, winding driveway of the Orchiston farm. There, laid out before their incredulous eyes, were over 50 distinct varieties of harakeke, all carefully catalogued. The job had already been done.

“It was a fantastic find,” says Scheele, “but what gives this collection even greater significance is that it was made available to the public of New Zealand.” This happened in 1987, when Orchiston donated her entire collection to the DSIR to form the basis of a national collection. Landcare Research—Manaaki Whenua took over stewardship of the Orchiston Collection in 1992, when the DSIR was disbanded. Ongoing research into taxonomy, fibre properties and management will ensure we will be even more knowledgeable about flax in years to come.

The collection has now been replicated on sites at Havelock North, Rotorua, Taupo, Gisborne, Golden Bay and Lincoln. Since flax varieties do not necessarily grow true from seed, the plants are propagated vegetatively from suckering fans. These are made freely available to weavers, and thousands of new plants have made their way into the gardens of marae, community groups and schools—a heritage saved.

The ironic thing about New Zealand flax is that it isn’t a true flax at all. It is in a family of its own (related to the lilies), which is endemic to this country and Norfolk Island. Indeed, the Phormiaceae is the nearest thing we have to an endemic plant family. Not even our closest botanical neighbour, Tasmania, possesses anything quite like it.

The common name “flax” was given by early European traders because of the similarity between its fibre and that of the true flax plant, Linum usitatissimum.

Linum flax has been actively cultivated for fibre, linseed oil and its many derivatives (including such materials as linoleum) since Babylonian days. Wallsof burial chambers dated 3000 B.C. depict toil in large flax fields, and the tombs themselves contain intricate examples of early linen textiles. Linen fibre is still used in garment fabric, canvas, twine, fishing nets and even cigarette papers.

Worldwide, there have always been plenty of worthy substitutes to get by on if you couldn’t grow or afford products manufactured from the temperate linum flax. Harder fibres such as sisal and manila supported whole colonial empires, but it was the softer jutes and hemps that rated as linum’s real competitors.

It was a totally different story in our corner of the Pacific, though. New Zealand’s earliest immigrants must have felt at a real disadvantage for the first few years without their usual coconut, pandanus and bark cloth supplies, for back in their tropical homeland products from these plants gave rise to virtually everything they used. In the land of the long white cloud these essential plants were not only absent but unable to grow in the cooler climate.

Captain Cook recorded seeing a small grove of aute, paper mulberry, growing in the Bay of Islands. Used for making tapa cloth, aute grows freely in Tonga and Samoa, but the Maori-introduced plant appears to have died out here, although small groves have recently been re-established in the Far North. It has been seriously postulated that had they not found flax here, Maori settlement of New Zealand might simply not have been successful.

Maori recognised two distinct species of flax The common flax found in lowlands or swamps, Phormium tenax, they called harakeke. An evergreen growing in upright clumps, its flowers are waxy red, yellow or orange, with the seed pods pointing upwards on the scapes—the leafless stalks that arise from a basal clump of leaves. The smaller mountain flax, Phormium cookianum, was called wharariki. Plants rarely exceed 1.6 m high and often have droopy leaves. The flowers are usually yellow-toned, with twisted seedpods hanging down off the scapes. These hanging seedpods are the most consistent point of difference between wharariki and harakeke. Common on rocky outcrops in montane areas throughout the country, wharariki often has a weatherbeaten, scruffy look.

Confusingly, mountain flax also thrives along our coastline as well, growing bravely in the face of wind-driven salt spray. The spectacle of whole hillsides and headlands Mexican-waving in the gusts stops me in my tracks every time I am driving in the vicinity of Cook Strait. Some of my fondest childhood memories of the Wellington south coast are of fighting my way through thick flax to get to the rocky bays.

Botanists today wonder whether there may be more flax species awaiting description. “The two existing species are highly variable,” Landcare’s Peter Heenan tells me in that guarded manner which scientists have perfected. “Until we sort out the extent of natural variation and the extent of hybridisation between the two existing species, we won’t know if there are further species.”

Peter de Lange of the Department of Conservation is less equivocal. “The plant on Norfolk is definitely a new species. There is at least one new species on the northern offshore islands, such as the Three Kings, Mokohinaus and Poor Knights. The Chatham Islands have their own distinct species—one which has very poor fibre. The Taranaki Maori took their own flax with them when they invaded the islands last century, so there are two species there now. And the coastal version of cookianum is not true cookianum, which has a black stripe in the leaf and is only found at higher elevations.”

[Chapter Break]

The importance of flax to early Maori cannot be overstated. It was Maui’s godsend, the most important thing to them after food. When informed that flax did not grow in England, some chiefs are reported to have asked, “How is it possible to live there without it?”

To the first canoe-loads of settlers, the size, shape and strength of flax leaves would have immediately suggested the plaiting of mats and baskets, a skill well represented in all Polynesian cultures.

But that was just for starters. Harakeke would soon became transformed into platters to eat from, buckets to carry soil and sand for cultivating gardens and building fortifications, lines and nets for fishing, mats to sleep on and to cover floors, lashings for canoes and dwellings, snares to trap birds, sails for canoes, sandals to protect the feet of travellers. Maori babies were given rattles made from flax, and every boy knew how to flick a flax dart. Splints for broken bones were made from leaf bases, and flax fibres or strips used for sewing up a wound. You name it, Maori found a way to do it with harakeke.

And flax proved a veritable pharmacopoeia for Maui’s descendants. Murdoch Riley, author of Maori Healing and Herbal, devotes 10 pages to the medicinal uses of flax leaves, gum, rhizomes and stalks. For instance, the twisted, woody rhizomes roasted on hot stones, then macerated, became an effective poultice for abscesses and ulcers. Boiled leaf bases and roots made such a strong purgative that manuka capsules had to be kept handy for chewing as an antidote! Flax root juice was routinely applied to wounds as a disinfectant, and the soothing antiseptic properties of the gum, found at the base of the sheaths, used to be widely appreciated for healing burns and ringworm. Toothache was treated with a few drops of juice from root or leaf base in the cavity of the affected tooth or in the nearer ear.

Flax was also prominent in the Maori augury. If a leaf made a screeching sound as it was pulled from the base of a plant during an appropriate ceremony, a tohunga’s patient would recover. If the sound was produced during a ceremony before a fishing trip, a big catch was certain. A flax leaf was suspended directly over the mouth of a dying person as a path for their last breaths. If the ends of the leaves of a flax clump were found knotted together, it was a sign that the spirits of the departed had passed by.

The abundant nectar from flax flowers was a favourite beverage and food sweetener. The phrase “me he wai korari,” literally “like the nectar of the flax,” might in today’s hip argot be translated “Sweet as!” During a self-sufficiency phase, I once extracted flax syrup by squeezing the flower pods. I saved on sugar, but I couldn’t cope for long with the gritty aftertaste. Maori children usually collected the nectar by tapping flowers they had picked against the inside of a gourd. A big plant might produce up to 250 ml of liquid. Diluted with water, it was used as a drink. It was also mixed with meal from the roots and stems of cabbage tree and bracken fern. These days, tui and bellbirds have less human competition for nectar, though near urban areas they have to compete with introduced species such as waxeyes and starlings.

Resourceful Maori didn’t even let the flower stalks go to waste once they died and dried out. Snapped off and tied into tight bundles, they made a perfect raft to float an intrepid traveller across a lake or flooded river.

Harakeke was the stuff of legend, too. Maui knew he could rely on his specially woven canoe hawser for perhaps his greatest deed: lassoing and reining in the sun.

But plaiting the leaves of unprocessed flax did have its limitations. Garments made from it never fitted properly and felt rough to the skin. Perhaps spurred on by the demands of a harsher climate, as much as by comfort considerations, Maori weavers discovered that by drawing harakeke across a sharp edge such as a mussel shell they could scrape off the tough backing layer of the leaf and be left with soft, silky strands of inner fibre known as muka. This dressing of the flax, a process called haro, was the first stage in the laborious manufacture of the warm, beautiful crafted garments that so impressed early Europeans.

In the Marlborough Sounds, Captain Cook called the flax garments he saw there “the most curiously worked . . . made from a plant that serves the inhabitants instead of hemp and linum, which excels all that are put to the same purposes in other countries. Indeed, their uses for harakeke just seem endless.” No doubt this observation inspired him to introduce the plant to England upon his return. Unwittingly, maybe, he took Phormium cookianum varieties, the descendants of which can still be viewed in London’s Kew Gardens. It was Cook’s father-and-son botany team of George and Johann Forster who gave flax its scientific name: Phormium after the Greek for basket, and tenax, Latin for strong. The Maori “hara” in harakeke is derived from Polynesian names for pandanus (eg. ‘ara in Cook Island Maori) and “keke” meaning strong or stubborn.

The Russian expedition of Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen to the Marlborough Sounds in 1820 bartered not only for samples of finished Maori garments, but unfinished ones as well—to illustrate their complex construction. The Russians also took flax seed, exchanged for seed of turnips, swedes, carrots, pumpkins, broad beans and peas. Bellingshausen thought southern Crimea shared similar soils and climate to the Sounds, and planted his seeds there. Thriving patches of Phormium tenax still exist around the Black Sea.

[Chapter Break]

Maori had a flax for every purpose. Heavy-duty, long-fibred Tihore types were ideal for ropes and netssalt-resistant, even. The short, finer Takirikau flaxes, stripped easily even by a thumbnail, were ideal for making piupiu (a waist garment with a free swinging fringe).Very long, bendy varieties such as Atewhiki were used for making wharaki (mats) and kete (baskets). Blackedged, slightly droopy blue-green flaxes could be relied on to produce long ribbons of soft, silky muka which might be further processed by soaking, beating and rubbing, all depending on its final use. Processing the flax was laborious work, carried out mostly, but not always, by women. Jerningham Wakefield, in Adventures in New Zealand (1845), described men making flax cloaks for sale to Pakeha. The bindings for weapons were also men’s work, and when a marae needed a new fishing net, everyone pitched in.

Hauraki Maori believed that the techniques of weaving and plaiting were acquired from a patupaiarehe, or fairy, named Hine-rehia. This textile expert married a mortal, but carried on weaving only at night in proper fairy fashion. At dawn she would put away her unfinished work, because the sun was capable of undoing not only her work, but also her skills.

Anxious to learn the fairy’s secrets in the light of day, the women of Motuihe used a tohunga to confuse her senses so that she would carry on weaving after the sun rose. Learn her skills they did, but it was not long before Hine-rehia realised that she had been tricked. She sang a sad farewell to her husband and children before a cloud bore her away to the Moehau Range. Sometimes, in deep fog, her lament can still be heard.

However they acquired the skills, the making of garments was the pinnacle of Maori flax technology, and a whole haute couture evolved around it. The style of cloak indicated an individual’s rank The first Europeans to arrive here in the late 18th century were greeted by chiefs wearing dogskin cloaks (kahu kuri). Such a garment, which bestowed much mana on its wearer, was made by attaching narrow strips of the skin of the highly prized Polynesian dog to a woven flax foundation (kaupapa). Other cloaks were decorated with feathers or dog hair.

Kaitaka were more restrained, but more elegant. Made of finest muka, the focus of decoration on these cloaks is an exquisite border of taniko, an almost forgotten type of weaving. An expert weaver could easily spend a year making one of these. No tools or looms were used, just superlatively deft hands with the strip of work suspended between two weaving pegs stuck in the ground like a miniature volleyball net.

No wonder, then, that for Maori these beautiful garments became taongatreasures. They embodied great spiritual power and prestige, derived not only from the revered artist who created them and the ancestors evoked in the decoration, but also from those who actually owned and handled them. An exalted cloak would be honoured with a personal name. Such a cloak, if cast by the wearer over a condemned man, would save his life. Auckland Museum’s intricately carved war canoe Te Told a Tapiri, built in the 1840s by the Ngati Matawhaiti, was handed over to chief Te Waaka Perohuka of Rongowhakaata in exchange for his famous cloak Karamaene.

The art world has yet to wake up to the quality of Maori weaving. In his book Te Aho Tapu, The Sacred Thread, ethnologist Mick Pendergrast makes the point that, compared to other aspects of Maori artistry, the manufacture of fine kakahu (cloaks) has not received recognition.

“It’s difficult to understand why . . . because whenever they are displayed they are universally admired and recognised as equal in skill and beauty to the finest costumes of other lands,” he writes.

One problem with exhibiting fine woven work is the fragility of the objects and the difficulty of handling them. Some of the finest examples of kakahu cannot be displayed for fear of damage.

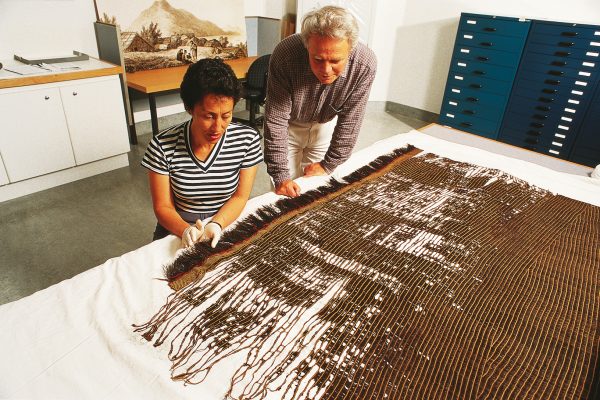

Rangi Te Kanawa, grand-daughter of the late Dame Rangimarie Hetet, one of the last great muka weavers, is one of five textile conservators in this country. Deep within the Museum of New Zealand, Te Papa Tongarewa, I join her and Industrial Research chemist Gerald Smith as they explain their collaborative project: the search for a method to overcome the single biggest problem faced by conservators of Maori fibres—paru-induced degradation.

“Maori routinely dyed their garments black with paru, a smooth greyish mud containing iron and tannin,” Te Kanawa explains. “Flax is relatively stable by itself, but once it’s dyed with paru, it seems to have a limited life. We have to come up with a way of stabilising these paru-dyed textiles before they disintegrate.”

We all put on the surgical gloves used for handling delicate fibrous material. Gingerly I assist with unravelling an oversize roll of soft foam, to reveal within a magnificent kaitaka—a finely woven style of cloak with a characteristic silky sheen. But this one is in deplorable condition. Whole areas of once-fine black weave have just rotted out, as if motheaten.

Smith explains the challenge they face: “We know that degradation of the fibre is caused by increasing acidity due to oxidation of the paru. Now we are concentrating on finding out exactly what conditions we should be storing these dyed fibres in. Light and relative humidity play a big part, and we’re still doing experiments under nitrogen, oxygen and carbon dioxide. It’s looking very much like a case of having to keep our best weavings in the dark under controlled humidity if we want them to survive.”

I admire the intricate wefts of the garment. Te Kanawa tells me the backbone strands were made by double pair twining, a process involving the twining of four threads instead of a single pair. It is a very advanced weaving technique, she says, largely lost worldwide. “When I demonstrated it to some French textile historians at a conference recently, they were just blown away. They thought it had died out, like many of the finer aspects of the weaver’s craft which have been lost here.”

As part of the Maori cultural renaissance, harakeke work is staging a comeback at the hands of a dedicated band of flax weavers nationwide. In 1983, Aotearoa Moana a Kiwa Weavers was formed under the direction of the late Ngoi Pewhairangi, whose exhortation: “Ka raranga tonu tatou i a tatou”—Let us weave ourselves together—stressed the need to pool skills and resources for the survival of the craft.

Another group, Te Roopu Raranga/Whatu o Aotearoa (Maori weavers of New Zealand), seeks to nurture and preserve the techniques of raranga, whatu, and taniko (the three traditional forms of weaving) by arranging hui and wananga (teaching sessions) and holding exhibitions.

The resurgence in harakeke weaving awareness comes with a large body of tradition and ritual associated with flax. In earlier times, the observance of these customs and rituals was seen as a necessary part of successfully acquiring and retaining the skills. In “The Art of the Whare Pora” (1899), ethnologist Elsdon Best described the induction of young women into the ways and lore of the whare pora, the house of weaving. This was not a physical building, rather a guild of craftswomen. Young women were initiated into it by a tohunga. The novice (tauira) sat behind a pair of turuturu (cloak-weaving pegs), and fine examples of weaving were spread about. Special karakia were uttered by the tohunga, and then the tauira, holding a handful of prepared fibre, bent forward and bit the top of the right-hand weaving peg, which was considered sacred. Using the prepared fibre, she then wove the first line of her garment, the aho tapu or sacred thread, and tapu was lifted from the weaver and her work.

Rituals were involved at every step of the weaving process, designed to protect the vital qualities of the plant and the work of the weaver. Flax, for instance, was never cut in the rain or at night. There was no eating while working—today even the use of culinary knives for cutting flax is frowned upon. Children were discouraged from touching or stepping over even unused materials, perhaps to imbue them with an appropriate respect for the craft. Some protocols applied to harakeke horticulture. For example, when transplanting a flax fan “put his puku to the sun”—that is, the concave side, so it collects maximum light.

Some of the old traditions, however, have had to be altered. In a world out of kilter, the practice of depositing bundles of leftover leaves under the plant to rot into compost is not advisable. The dry rolled-up leaf tubes make perfect homes for the larvae and pupae of flax pests which once used to be better controlled by seasonal flooding and marauding weka.

[Chapter Break]

Flax played a huge part in the making of our nation, but not just for Maori. European settlers were quick to recognise the export value of the fibre. The first major shipment to London, a sizeable 60 tons valued at £2600, left these shores prior to 1818. By 1830, a regular export flax trade had been established, with £50,000-worth of the New Zealand fibre being auctioned in Sydney alone between 1828 and 1832. Flax was this country’s biggest export by far until wool and frozen mutton kicked in late in the 19th century.

Entrepreneurial flax traders employed Maori workers to hand-strip the flax in exchange for blankets, trinkets and, most importantly, muskets. The price for a musket quickly became set at one ton of dressed flax, with still more required for powder and ammunition. Inland tribes, desperate for the muskets their coastal brethren and enemies possessed, exchanged slaves for muskets—three to five slaves for a musket. Slaves were useful as human flax-stripping machines.

Maori even abandoned their hilltop pa to settle nearer to the swamps in which flax grew—and often suffered poor health as a consequence. Muskets and flax changed their whole way of living—and dying. And for what? In 1831, one ton of New Zealand flax fibre was fetching between £18 and £25 on the English market, most of it destined to end up as cheap rope.

Today it is impossible to imagine how laborious the hand dressing of flax was. Colonel Theodore Haultain, one of the flax commissioners appointed by the colonial government in 1870 to investigate the full potential of the industry, wrote: “It is difficult to get any accurate estimate of what quantity a Native woman can prepare in a day, but it is not much. At a large meeting [near Waikanae] I asked the question . . . some could do 1 lb, some 2 lb, and others as much as 4 lb, according as they were fortunate or otherwise in quickly finding the proper leaves.”

It was menial work for menial wages. Haultain would soon be reporting: “The Natives of Otaki are not preparing any of the fine flax, they think the price insufficient. I tried to induce T Rauparaha to take it in hand . . . but he seemed to think the attempt was useless.”

Haultain travelled the country tirelessly, canvassing various tribes in his feasibility study. The answer seemed always the same. “The Natives at Opunake, after some consideration, declined to prepare any fibre . . . They said that the work was too much, and the price too little.”

“If Europeans won’t do it for a pittance, why should we Maori?” went the cry. This not unreasonable position hardened during the New Zealand Wars. Between 1860 and 1866, the average annual value of flax fibre exported plummeted to a mere £150.

It took a conflict on the other side of the world to stimulate a flagging industry. The American Civil War created an unprecedented demand for manila rope, produced almost entirely by dirt-cheap manual labour in the Philippines. The price of the product skyrocketed from its customary £21 pounds a ton to a peak of £76 pounds during the height of the conflict. Such high prices stimulated attempts to introduce New Zealand flax fibre as a direct competitor to manila.

Happily, by 1868 the problem of how to separate fibre from flax leaf rapidly and cheaply was solved by the invention of the flax stripper. This machine used a rapidly rotating drum to scrape and beat the leaves into yielding up their fibres. Within just two years, export receipts for our flax had skyrocketed to £132,578 per annum. By 1906, there were 240 flax mills dotted throughout the country, employing over 4000 “flaxies,” who collectively produced fibre for export that brought in over half a million pounds a year. Most mills were sited near swamps and could be recognised from a distance by the high-pitched scream emitted by the strippers. Outside, acres of drying fibre could be seen hanging on fences.

The country’s largest flax mill by far was called Miranui and was built in 1907 in an area known as the Makerua Swamp, or simply the “great swamp.” This area of 5800 hectares stretched from three kilometres north of Shannon along the Manawatu River up to Linton, and once supported a huge crop of vigorously growing flax. During the height of the flax industry in 1916-17 there were 19 mills in this swamp, operating 42 flax-stripping machines and employing over 700 workers. Many older people in the district still remember the convoys of 50 or more “flaxies” riding their bicycles every morning out from Shannon to work in the swamp.

Miranui was capable of producing 2500 tons of fibre from 22,000 tons of flax leaf annually, and it exported over one million pounds’ worth of fibre during its 26-year operation, marketed under the brand “Nui.”

To say you worked at Miranui, or just “the big mill,” was to be envied by other flax workers. Not only did it have a big dining room and bunkhouses, but it was the ultimate in flaxmill design, operating seven strippers in the main building, which was a massive 62 metres long by 23 metres wide. Two more strippers operated in a smaller building alongside.

Workers had to manually feed the ever-hungry strippers. No Occupational Safety and Health regulations back then! These deafening mechanical monsters beat the cut flax leaves between a revolving drum and a stationary bar, raised projections tearing off the outer skin of the plant and exposing the fibre.

Before mechanical methods of collecting the newly stripped fibre were developed, a teenage boy or old man sat beneath the stripper to catch the fibre as it dropped out of the machine. In this position—nicknamed the glory hole—the occupant was plastered with a constant rain of slimy leaf material, and emerged bearing more resemblance to a frog than a human.

After stripping, the hanks of fibre were washed and laid out in paddocks for drying and bleaching in the sun. There were more than 100 hectares of bleaching paddocks at Miranui. Once dry, the fibre was scutched in another revolving drum machine—one which featured wooden beaters to clean and polish the fibre.

No machine-stripped fibre could ever match the fine, long silky strands drawn out by a pair of Maori hands. Mechanical beaters flogged the fibre dreadfully, sapping its strength and making it suitable only for the manufacture of ropes, twines, bags, sacks and coarse matting. From time to time, flax enthusiasts such as Miranui’s owner, Alfred Seifert, experimented with alternative processes (chemical and mechanical) that would produce either stronger fibre suitable for heavy industrial use, or softer fibre capable of being woven into textiles. Unfortunately, these experiments were never commercially successful.

A unique feature of Miranui was a narrow-gauge tramway which ran from the mill six kilometres into the swamp. But even the small five-tonne steam locomotive proved too heavy on the swampy ground, and it was later sold to work the bush tramways in Auckland’s Waitakere Ranges. From 1910, teams of half-draught horses were called in to haul wagons on Miranui’s flax tramway. Three horses were required to haul a train of nine trams, which, fully laden, weighed a tonne each. “Trammies” not only drove the horses, but also laid the rails into the blocks of flax. Over 200 metres of tramline had to be pulled up and relaid every day.

The First World War saw New Zealand’s flax exports peak at over 30,000 tons a year and prices rise to £50 a ton, but a surreptitious foe was already infiltrating our flax fields. Flax yellow leaf disease was first reported in 1908, and by 1920 it had devastated large areas of the big swamp. This disease is caused by a phytoplasma—an unusual type of bacterium—spread by a hopper insect, and is believed to be similar to the organism causing “sudden decline” in cabbage trees. In affected plants nutrients no longer reach the leaves, causing them to turn yellow and stunting their growth.

Smaller mills were forced to close due to a shortage of healthy leaf. Worried mill owners hired eminent government botanist Leonard Cockayne to investigate. But no cure could be found, and popular opinion ran that the gradual draining of the swamp to farmland had precipitated the problem. Around half the flax crop was eventually destroyed.

In a desperate attempt to save the foundering industry, a new method of cutting the flax was tried. Flaxies used to slash down the whole clump with a sharp hook, and it would be another four or five years before the plant would have recovered enough to be cut again. Side-leafing—nothing new to the Maori—involves only the mature leaves of the flax plant being cut, leaving the centre shoot (rito) and two supporting leaves to begin the growing process again. Results were dramatic. Production costs increased by around 8s 6d a ton, but the new practice increased yields by up to 90 per cent, because each plant could be cut yearly.

[sidebar-1]

Unfortunately, the success of side-leafing was short lived. After a became obvious that continuous cutting was adversely affecting Successively harvested flax was always smaller than the yield the year before. Faced with falling prices in a world recession, Miranui owners called it quits in 1933, and the staff of 50 (a far cry from 300 at peak production) all sought government relief work. Only remnants of the scutching shed can be found today.

While the Manawatu was the largest producer of flax fibre, flaxmills also played a part in the economic development of other parts of the country, including Southland, Westland, Northland, the Bay of Plenty and Marlborough.

Ian Matheson, head of Palmerston North Library’s archives and currently writing a book on flax, points out that many individuals were boosted up the ladder of success by the proceeds of flax. “Lord Rutherford’s father was a flaxmiller in Nelson and Taranaki during the 1880s and 1890s,” he says. “Profits from his business helped give young Ernest a start in life. Just think, the humble flax plant indirectly contributed to the splitting of the atom!”

[Chapter Break]

Delph Halidone of Foxton is 82, his face weatherbeaten and etched from a life of outdoor toil. He left school at the age of 14 to join his father, brothers and uncles—all of whom worked the flax. He almost made World War II, but a day before he was due to be called up, he got five of his fingers ripped off by the flax stripper that he was operating. “Don’t know which was more dangerous, going to war or working in a flax mill! I learnt to cope with less fingers—you carried on working in those days.”

It is impossible to tell the story of flax without mention of Foxton, the small town on the Manawatu River that t ecame the centre of the nation’s flaxmilling industry. The prosperity of the town rose and fell with the fortunes of the flax plant. When overseas prices were high, Foxton was a boomtown where the whine of the stripping machines assailed the ear night and day, six days a week. When prices were down, Foxton slumped and the flaxies left town to search for work elsewhere. Two-thirds of Foxton’s labour force depended on the flax plant for their livelihoods, and some families worked in the flax industry for three or four generations. These families often intermarried, creating a working-class solidarity similar to that experienced in the coal-mining communities of Westland.

Foxton obtained its flax supply from the Moutoa Swamp, a 2000-hectare wetland on the north bank of the Manawatu River, stretching eastward towards Shannon. This swamp was considerably smaller than the great Makerua Swamp, but had a much longer history of flax production, supplying green leaf to flaxmills for over 100 years (1869 to 1985). In the early days, bundles of cut flax were transported down the Manawatu River on wooden punts towed by steam launches. After the 1920s, lorries carted the flax by road.

The Moutoa Swamp was purchased by the government in 1939. Over the next 30 years the Department of Agriculture gradually transformed the area from a wetland supporting natural varieties of flax to a dryland growing selected cultivars of the plant. Its official name was the Moutoa Estate Phormium

Development Area, but the residents of Foxton continued to call it “the swamp.”

Tens of thousands of flax fans (divided from the rootstock of parent plants) were planted by hand in rows and harvested by hand every four or five years. Experiments with machines for planting and cutting all proved unsuccessful.

During the 1970s and ’80s the land was converted into pasture, and is now used for dairy farming. Only one patch of flax remains, a small reserve of 50 hectares controlled by the Department of Conservation. Largely forgotten, access is by a rough gravel track alongside a flood protection bank of the Manawatu River.

The place has a desolate windswept feel to it these days, reminiscent of the isolation that must have been experienced by conscientious objectors exiled here in World War II. About 100 of these men were sent to camps in the Moutoa Swamp, where they assisted the war effort and the phormium development programme by clearing noxious weeds, digging drains and planting flax. It was lonely, backbreaking work.

The onset of the Depression in 1929 saw flax exports collapse from 20,000 tons in 1928 to less than 4000 tons two years later. Prices fell too. After 1940, the country never exported more than 1000 tons of flax fibre a year, and generally the amount was less than 100 tons.

But the flax business was by no means dead. During and after the war, the government provided subsidies on flax production as an insurance, lest political instability elsewhere in the world should sever our access to other fibres. Meeting this internal demand kept 15-20 smaller flaxmills busy until about 1970, producing 5000-6000 tons of fibre each year. The main product was flax woolpacks—restrictions having been placed on the import of rival packs made from Indian jute. This policy protected the jobs of 200 workers in Foxton, where a large factory spun and wove the fibre into woolpack cloth. The government also spent money on studying the quality of different varieties of flax. Breeding and selection work resulted in a cultivar named S.S. (Seifert Superior) being planted in the Moutoa Estate, and it provided much of the raw material for the woolpack factory.

The last commercial flax stripper in use, at Bonded Felts in Foxton, fell silent in 1985, when fire gutted the building. This operation was capable of handling 16 tonnes of green flax leaf a day.

Yet flax is not forgotten. What fanner cannot recall with nostalgia the old straw-coloured baling twine made from flax? Strong, yet biodegradable, it was made until the early 1970s. You didn’t feel quite the same need for heroics as you watched the end of it disappear into the mouth of a prize bull as you do with the indestructible synthetic stuff. The natural twine still available is made from imported sisal—a plant related to the cabbage tree, native to Mexico.

Flax fibre made a third of our woolpacks, and turned up in underfelt, floor coverings, plasterboard, lagging and upholstery. Remember those coarse brown tumble mats in the school gym? Imported overseas fibres were never the same. If it had to be thrashed, it got made from flax.

[Chapter Break]

The decline in the flax fibre industry was perhaps inevitable, given the advent of cheap synthetics and modern technology. Yet today, with the pendulum swinging towards more natural products, it is easy to envisage a future for flax. Grant Cavaney, 66, owns Opunake’s chemist shop, continuing a tradition in his family of dispensing medicines that goes back nonstop for over 150 years. As a child in Taranaki just before World War II, he spent much time tailing behind a remarkable Maori woman who was also the area’s district nurse.

“She would always be explaining to me traditional Maori remedies and medicines, including how to prepare them,” he recalls. “The curative, antifungal and antiseptic properties of flax were never lost on me.”

Much later, in 1982, he began making soap out of flax, extracting it just as his Maori mentor had taught him. Nowadays his small-scale manufacturing operation, Brevis Pharmaceuticals (named after a rare Mt Egmont daisy), is set up just across the road from his shop. It employs up to four staff, and turns out a steady 1.5 tonnes of vegetable oil soaps a month. Not to mention a line of flax hand creme and shampoo, his latest products.

“We’ve found a niche market,” he tells me. “Farmers like the soap because it has gained a reputation to quickly heal cuts and scratches. The best remedies and medicines are sourced locally. Why should we be using imported products when it’s all here?”

There are other possibilities for flax, too. Experiments carried out in the USA during the 1930s tested Phormium fibre for papermaking. The quality was high, provided the fibre was properly cleaned. New Zealand Forest Products did trials in the 1980s with a view to using Phormium for banknotes. Certainly, flax makes lovely handmade paper, but the economics of mass production don’t stack up yet.

While we’re at it, what about flax plonk? Experiments done by the former DSIR on fresh flax refuse yielded 50 to 60 per cent juice, which fermented readily to produce between two and five per cent alcohol. Who knows: in the future, flax in a bottle!

Further chemical investigations during the 1960s showed that Phormium tenax has a high proportion of essential fatty acids. The seed oil contains linoleic acid in amounts that surpass those found in sunflower and safflower seed oils. Linoleic acid is used industrially, and is essential for human nutrition. Experiments showed P. tenax could produce 150 kg of the acid per hectare. One American researcher has even isolated two new cucurbitacins from the plant—compounds with possible potential as tumour inhibitors.

[Chapter Break]

Perhaps the only person today who is making a living solely from the growing of New Zealand flax is Margaret Jones, who lives just out of Tauranga. As New Zealand Flax Hybridisers, she has been responsible for the selective breeding and release of 18 new Phormium cultivars, among them Crimson Devil, Dark Delight, Cream Delight, Duet, Sunset and Evening Glow. Many cultivars have been grown for their merits as cut foliage. Brightly coloured and with extraordinary vase life, the leaves can also be split for interesting effects.

Jones explains how it all began, nearly 30 years ago: “We discovered a P. cookianum ‘Tricolor’ in our garden that had produced a most unusual sport. It was lifted, divided and nurtured and, even though others reckoned it would not be stable enough because it did not have enough green pigment in its leaves, we began marketing it in 1978 as Cream Delight. After 21 years and many thousands of plants, Cream Delight has disproved all those early doubters. Only once has it reverted back to its parent plant.”

When it comes to creating new cultivars, Jones relies on intuition: “I see two flaxes that I like and just plant them together and hope.”

Her only cheap labour are the tui that so diligently carry out the task of pollination. Seed pods are gathered when dry and sown under compost.

“The end results can be something quite ordinary, or there might be a single treasure. Out of 3000 seedlings—`pups,’ I call them—perhaps only one is special enough to keep.”

Getting large numbers of plants to sell from that one special plant is tedious work. Seeds don’t breed true, and micropropagation techniques fail with flax. So new shoots just have to be teased off the parent plant and planted out—at a rate of two or three a year per plant.

Anything seems possible with flax. From floristry to fine fabrics, paper to medicines, even alcohol. With the application of a little modern technology, a New Zealand flax industry could once again become a thriving concern. Do we really need hemp—heavily promoted today as a fibre plant and saviour for agriculture—when we have flax already?

The linen years

At the start of World War II, the call went out from Britain to many of her former colonies: “We need flax!”

What Britain wanted was linen flax—”true” flax—until then supplied by the Netherlands and Belgium, which had fallen to the German Reich. New Zealand, along with Ireland, Australia, Canada, the USA, Kenya, Egypt and a number of South American republics, was prevailed upon to make good the shortage.

Linen was urgently needed as fuselage and wing fabric for aircraft such as Mosquito fighters and Wellington bombers (both had largely wooden airframes), and for a variety of other items, including fire hoses, heavy-duty canvas and parachute webbing.

Linen flax is obtained from a single-stalked, small-leafed annual called Linum usitatissimum. Stems grow to a height of 60-100 cm and branch near the top, bearing either blue or white flowers. For many South Islanders, the paddocks of blue flowers that became a feature of the landscape in the 1940s were to be a lasting wartime memory.

In 1939, the British government offered to finance a linen flax industry in New Zealand if 6070 ha were grown and processed. Before the first harvest, however, a request came to increase the area “to the uttermost limit.”

The challenges were considerable. Farmers had to be persuaded to grow the crop, while machinery had to be manufactured and factories built. Time, naturally, was of the essence.

Seventeen factories were constructed in total, all in the South Island. There were eight in Canterbury (Waikuku, Oxford, Leeston, Methven, Geraldine, Fairlie, Washdyke and Makikihi), four in Southland (Gore, Woodlands, Winton and Otautau), three in Otago (Balclutha, Clydevale and Tapanui) and two in Marlborough (Blenheim and Seddon).

The factories were designated Protected Places under wartime regulations, with guards mounted round the clock. Strict fire precautions were also required, owing to the flammable nature of flax fibre. The workforce was a mixture of retired men, school-leavers, unemployed men and women. Many were seconded to the work under the Industrial Man-Power Act.

Seed for the first planting was brought over from Britain, but thereafter locally grown seed was used. When the crop was ready, tractor-drawn pullers uprooted and sheaved the plants. At the factory, the sheaves were weighed and stacked, then fed into a deseeding machine where they were cut open and the seedheads, or bols, removed. These were crushed to release the seed, which was either kept for replanting or sent off for pressing to obtain linseed oil, used in paints and varnishes.

After deseeding, the flax was resheaved and placed in retting tanks, where it was soaked in hot water to rot the outside of the stems. When the tanks were drained several days later, the by-now stinking sheaves were removed and arranged in paddocks in long rows to dry.

The final processing step was scutching, in which the sheaves were beaten by a machine to remove remnants of outer stem and other detritus. The remaining fibre was then baled and exported to Britain for manufacture, although secrecy was such that no one knew precisely where. Damaged fibre was processed locally into tow, used to make string and rope.

Processing the flax was hard, physically punishing work. In the deseeding and scutching sheds, the air was filled with choking dust, and women’s hands were chafed and cut as they patted down the flax on the scutchers or combed the finished fibre with their fingers. Clearing the retting tanks was like working in a sauna, the heat and stench necessitating a daily bath and change of clothes. Many a finger was lost to the “wicked Irish Wheel”—the tow-processing machine.

While for some farmers the guaranteed price for linen fibre enabled them to pay off their farms, for others growing flax was not an economic enterprise. But at stake were issues far greater than mere finance. If Britain needed linen, then out in the Commonwealth all were expected to give of their best.

And New Zealanders rallied to the cause. On one occasion, when the harvest was ready but no machines were available, 500 volunteers in Gore—men, women and children—pulled 100 acres (40 ha) of flax by hand. For 10 days they worked from dawn till dusk, anxious to complete the job before the snow came.

One helper recalled: “To keep some of the old Scottish farming families happy about working on the Sabbath, we had to carry out the Salvation Army Band, who played hymns while the mob rooted up the farmer’s flax… Owners of stills in the Hokonui Hills turned out in force, with numerous bottles of their clandestine product—and that helped a lot!”

In the four seasons from 1940 to 1944, almost 104,000 tonnes of flax were harvested, but thereafter the demand from Britain waned.

With the war won, most of the factories closed in 1945 or soon afterwards. Only Geraldine, Fairlie and Winton continued with regular peacetime production into the 1950s, the last of these (Geraldine) closing in 1977.

+ Read sidebar

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)