Are electric cars a truly sustainable solution?

The car is the most widely used mode of transport in France, accounting for around two-thirds of all mobility1, in terms of the number of journeys, transport time and kilometres travelled. It is also a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for just over half of domestic transport emissions (excluding international transport), or 16% of emissions in France2. The automobile is therefore a key sector in the fight against global warming.

The electric car is seen as a solution for reducing the environmental impact of transport, being supported by public authorities, developed by manufacturers, and increasingly adopted by users.

Even if electric car sales have increased significantly since 2020, representing 10% of sales3 in 2021, they only represent a little over 1% of the number of cars currently on French roads. Nevertheless, political decisions support this growth, which is expected to continue. In France, the target date for the end of sales of combustion engine cars is currently 2040, while the EU is expected to bring this target forward to 20354.

To judge whether this electrification is good news and leads us towards sustainable mobility, we need to look at its advantages and disadvantages on several environmental, social, and economic impacts of mobility.

Mục Lục

Electrification is essential for climate objectives

Unlike internal combustion vehicles, the emissions from electric vehicles are zero when in use and are instead concentrated on the production of the vehicle and the power supply. The production of an electric car battery requires mineral resources. The extraction of which has an undeniable environmental impact, and their refining, like the production of batteries, also consumes energy. In the production phase of the vehicle, electric cars emit more greenhouse gases (in addition to other environmental impacts) than combustion cars, because of the addition of the battery.

It is in the use of the vehicle that the climate impact will be offset, especially for countries with a highly decarbonised electricity mix. In France, which is one of the countries with the best record in this respect, the electric car can already reduce greenhouse gas emissions by a factor of 3 compared with a combustion engine car (depending on the studies, the starting hypotheses and the type of vehicle studied, emissions are reduced by a factor of 2 to 5).

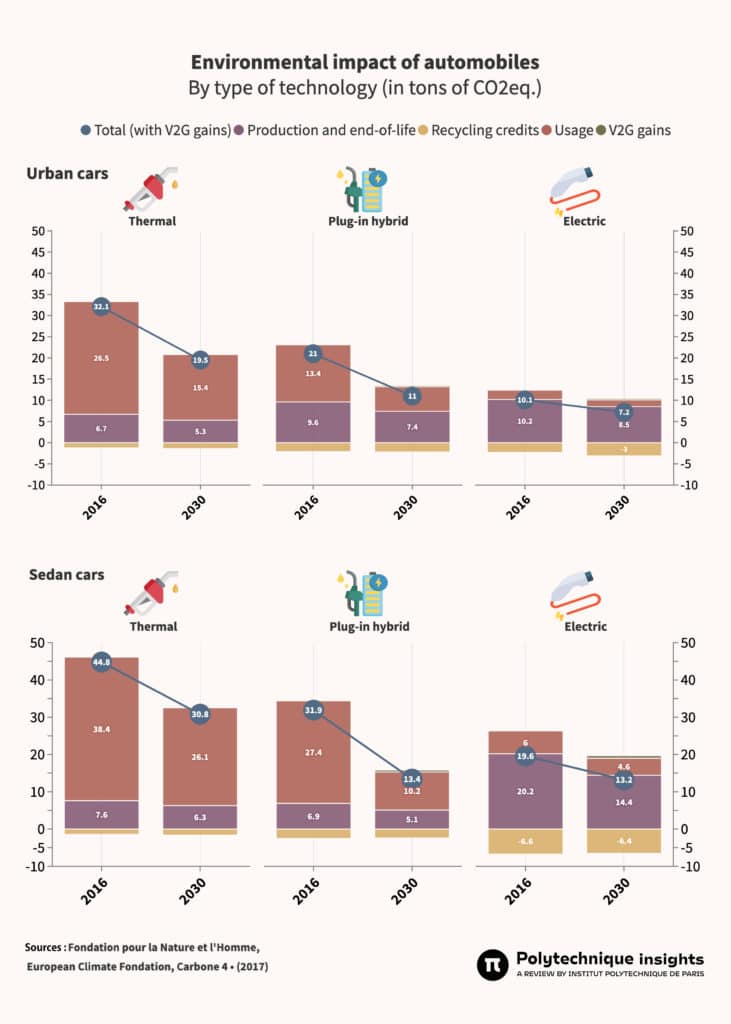

Carbon balance in life cycle analysis in tCO2e of thermal, plug-in hybrid and electric sedans in France, in 2016 and 2030 (FNH 20175). V2G: vehicle-to-grid is a technology that allows the redistribution of energy stored in the battery to the electronic grid6.

Carbon balance in life cycle analysis in tCO2e of thermal, plug-in hybrid and electric sedans in France, in 2016 and 2030 (FNH 20175). V2G: vehicle-to-grid is a technology that allows the redistribution of energy stored in the battery to the electronic grid6.

While other alternative to fossil fuels (hydrogen, biogas, agrofuels, or synthetic fuels) are not as suitable for light vehicles, electric power is a preferred and even essential solution for achieving our climate objectives in transport. The IPCC report7 states in its summary for policy makers that “electric vehicles powered by low-carbon electricity offer the greatest potential for decarbonisation of land transport in life cycle analysis”8. However, even a factor of 3 on emissions is not enough and would need to be improved by moving to much more fuel-efficient vehicles, as we shall see.

Putting air pollution gains into perspective

In addition to climate change, another important issue is air pollution, which affects health. The consequences for public health in France9 are mainly due to emissions of fine particles (PM), followed by nitrogen oxides (NOx) and ozone (O3). Depending on the pollutant, the transport sector has a more or less significant impact10: more than 60% for NOx and 17.5% for PM2.5 (particles with a diameter of less than 2.5 µm), although these proportions increase in the most densely populated areas, particularly along roadsides, where road transport accounts for more than half of the particles11, where population exposure can be significant.

Until now, tailpipe emissions have been the main source of air pollution from road transport. Significant progress has already been made on these issues for new vehicles, and electric vehicles will completely solve this problem for both fine particles and NOx.

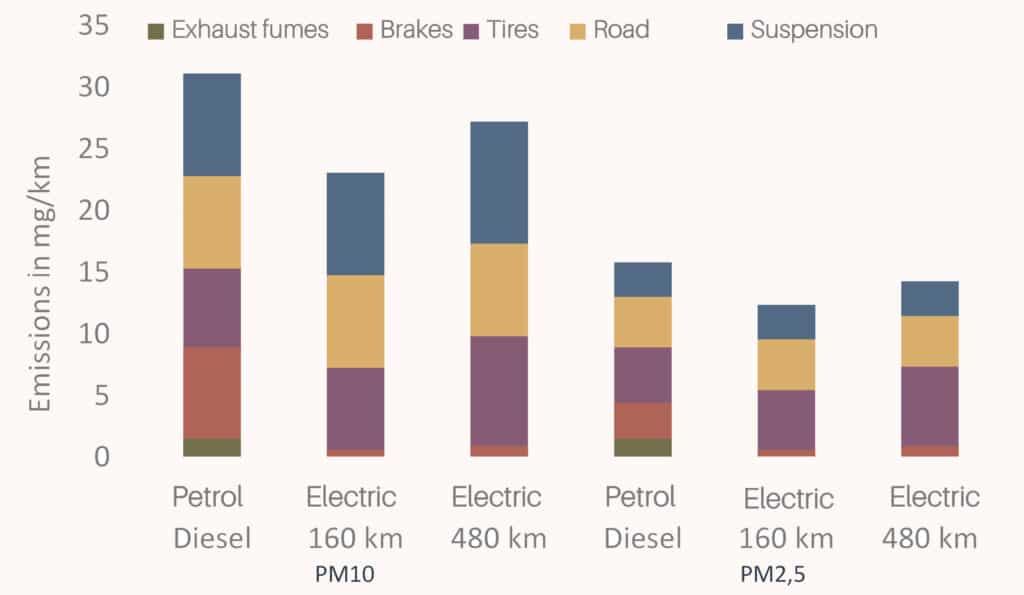

On the other hand, as a result of the progress made on fine particles from exhaust, the share of non-exhaust particles is becoming increasingly significant, representing 59% of PM10 and 45% of PM2.5 emissions12 in 2019 in France. These emissions correspond to the abrasion of brakes, tyres, and the road surface, as well as the resuspension of fine particles already present on the roads. Electric vehicles reduce emissions of particles from brakes through regenerative braking, but emissions are higher for particles from tyres and pavement because of their greater weight. Overall, emissions are somewhat lower for electric vehicles, especially given that the driving range, and therefore the weight, of the vehicle is limited.

Fine particle emissions from thermal and electric cars (ADEME 202213)

Fine particle emissions from thermal and electric cars (ADEME 202213)

Many impacts are too often forgotten

In terms of both greenhouse gas emissions and atmospheric pollutants, the electric car therefore appears to be a better choice than the internal combustion engine. But the amounts are still insufficient and should not overshadow the fact that emission levels are still high, particularly when compared with other modes of transport or forms of mobility that are more economical and more environmentally friendly. This is also the case for other impacts or externalities of transport, where the electric car does not solve the problems identified.

As with air pollution, noise pollution, an important factor in the quality of life, is reduced by electric vehicles without disappearing entirely. In fact, the noise of combustion engine vehicles comes not only from the engine, but also from tyre friction and aerodynamic noise, which is even more important at higher speeds, and these types of noises will not be significantly altered by electric cars.

Other car-related issues remain unchanged with the switch to electric cars. These include the space taken up by cars, which is often summarised as congestion, but which also concerns parking space (on roads, in buildings and car parks) and, more broadly, transport infrastructure, leading to soil artificialisation and impacts on biodiversity. The problems of accidentology also remain unchanged with the switch to electric vehicles. The car is also an inactive mode, and physical inactivity and sedentariness are a major public health issue, although too often forgotten since they concern no less than 95% of the population14.

The problem of unequal access to mobility, for social or geographical reasons, can be reinforced or reduced by switching to electric vehicles, depending on the circumstances. With a higher purchase price, at least for the time being, the distribution of the car to the most financially fragile populations is complicated, but the costs of use are then much lower, for an overall cost of ownership that remains high in comparison with the use of public transport, car sharing or even more active mobility, even if the lack of motorisation can sometimes require the use of car sharing.

Finally, regarding the consumption of resources, and in particular certain metals (lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, etc.), the electric vehicle may lead to new tensions compared to the internal combustion engine car, in terms of supply difficulties and price volatility, the limitation of certain resources or pollution linked to their exploitation.

Rethinking vehicles and mobility

Responding to these different issues together will therefore require going beyond a simple switch to electric cars – assuming it is possible to do so without major constraints, especially as the world’s car fleet is expected to grow in the coming decades.

The first step is to review the size of the cars or, more broadly, the vehicles used, which are not adapted today to everyday use, i.e., to the vast majority of uses. A car generally has five seats, can go up to 180 km/h, and weighs around 1.3 tonnes, whereas the most frequent uses are for one person, on roads limited to 80 or 90 km/h maximum (more rarely up to 130 km/h), for distances of a few kilometres to a few dozen kilometres.

Here again, the risk is that the race for greater driving range for electric vehicles will continue, when driving ranges of several hundred kilometres are only useful for a few rare journeys per year, at a financial cost to the buyer and with very significant environmental impacts. In the future, therefore, we need to develop much more fuel-efficient vehicles, i.e., smaller, lighter, less powerful, and less fast, more aerodynamic, with a limited driving range… which is the opposite of current trends, marked by heavy electric vehicles (such as SUVs) that do not meet any of the virtuous criteria mentioned above.

More broadly, the aim is to develop intermediate vehicles between the bicycle and the car, ranging from electrically assisted bicycles (EABs) to mini-cars (such as the Renault Twizy or Citroën Ami), as well as folding bicycles, cargo bikes, speed-pedelecs (electric bicycles which can achieve speeds of up to 45km/h) and velomobiles (recumbent bicycles with a fairing). These vehicles extend the possibilities of the traditional bicycle to replace the car, while making electric mobility much more accessible and much less impactful in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, pollutants, and consumption of resources and space.

Intermediate vehicles, adapted from15.

Intermediate vehicles, adapted from15.

More generally, we also need to review the place and uses of the car in mobility, by acting on the five levers of decarbonisation of mobility, cited by the national low-carbon strategy16, namely moderation of transport demand, by getting closer to people on a daily basis and reducing the longest journeys; modal shift, by favouring walking, cycling, trains, buses and coaches as much as possible (and in this order), well ahead of cars and planes, whose use must be reduced; by improving vehicle occupancy, in particular through carpooling; energy efficiency, which also concerns the reduction of speed on the roads, in addition to the levers of more environmentally friendly and electric vehicles already mentioned; and finally the decarbonisation of energy, in particular through electrification for the lightest vehicles, and also hydrogen, biogas, agrofuels, or synthetic fuels as a complement or for the other modes that are more difficult to electrify

If technology, and in particular this last lever, are major and indispensable, they must be placed in their rightful place in the transition, as the last levers of decarbonisation, after the previous levers which better enable the impacts of mobility to be tackled at the root and thus respond positively to more sustainability issues. As far as the car is concerned, the electric car must be encouraged, because it is the best alternative to get rid of oil, but it cannot be seen as a miracle cure… because it is not.

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)