All About the Business Cycle: Where Do Recessions Come From? | St. Louis Fed

![]()

“Expansions don’t die of old age.”

—Macroeconomic adage

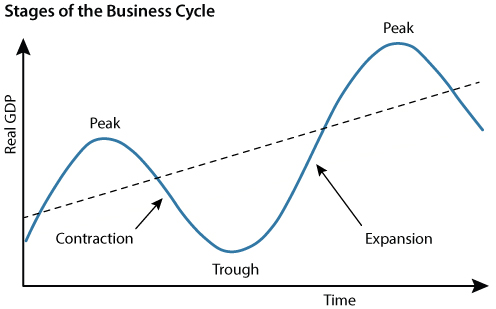

It might be tempting to think the stages of the business cycle are like the cycles on your dishwasher—regular cycles that occur in predictable patterns: The rinse cycle always begins after the wash cycle has completed, and each rinse always lasts the same length of time. In fact, the way business cycles are often illustrated in textbooks and websites often support this thinking (Figure). But there is nothing “regular” about the business cycle.

So, what does a “typical” business cycle look like? Business cycles include the following four stages:

1. The upward slope of the business cycle is called economic expansion. This is a period when economic output increases. That is, more goods and services are being produced in the economy.

2. It would sure be nice if the economy expanded continuously, but all expansions come to an end. In economic terms, each one reaches a peak, which, like a roller coaster ride, is the point just before the downward movement begins.

3. The downward slope of the business cycle is called economic contraction. This is a period when economic output declines; it’s measured as a decrease in real GDP. During this phase, the economy produces fewer goods and services than it did before. When fewer goods and services are produced, fewer resources are used by firms—including labor. As firms decrease their output, they will hire fewer new workers and often lay off some existing workers. As a result, when output falls, employment tends to fall as well.

Economic contractions often become recessions, which result in economic hardship for many people and can have long-lasting effects. For example, losing a job due to recession can lead to high levels of debt or the loss of key assets such as a house or car. In addition, if people are unemployed for long periods of time, they might find it difficult to keep their work skills sharp, and they might find it difficult to find another job.

While an economic contraction is objective—that is, it’s a measured decrease in real GDP—a recession is more subjective: The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) uses a variety of measures of economic activity, not just real GDP, to assess whether the US economy is in recession. We’ll discuss this more later in the essay.

4. Recessions are challenging, but fortunately they don’t last forever. In economic terms, each one reaches a trough, which is the point just before the upward movement begins—like the low point on a roller coaster run, just before the track turns upward.

What Causes Recessions?

If you watch the “talking heads” on financial news networks, you’ll sometimes hear them say that an expansion is getting a little “long in the tooth,” or that we are in the late stages of expansion. While they might have reasons for expecting the expansion to end, the phrasing can make it seem that expansions have a lifespan—that they end simply because they’ve been around for a while (like watching fruit start to go bad in your fridge and knowing you’ve got to throw it out soon).

That’s not how economic expansions work, though. In fact, economic theory suggests there is no reason for economic cycles to occur at all, as the economy’s natural state is expansion—positive growth.1 The economy gets knocked off its natural growth trend only when an economic shock knocks it off track. And, as the word suggests, a shock is an unexpected event.

These shocks can be positive (booms) or negative (recessions), and they come from a variety of sources. Economists suggest that shocks that cause recessions might include financial market disruptions, international disturbances, technology shocks, energy price shocks, and actions taken by monetary policymakers to restrain inflation.2 Of course, we’d like to avoid recessions; they are costly because unemployed workers (and resources) lose income and economic opportunities, and the economy loses output that cannot be regained.

Is Two Quarters of Negative Growth in Real GDP a Recession? It Depends

People often have heated discussions about whether the economy is in recession. How can you tell?

Using the informal “rule of thumb” definition, a recession is two consecutive quarters of economic contraction (negative real GDP growth). However, that is not the definition the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee uses. The NBER is a think tank with a very important role: It plays “referee” and decides when economic recessions occur in the United States.

According to the NBER, a recession is “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.” And the decline must be characterized, at least to some degree, by each of the following characteristics: depth, diffusion, and duration.3 Thus, emphasis is placed on a variety of measures of economic activity rather than on a single measure, such as GDP growth. In assessing the “decline in economic activity,” the NBER includes data about real personal income, nonfarm payroll employment, household employment, consumer spending, wholesale-retail sales, and industrial production in their assessment (Table 1).4

Because the NBER considers several economic indicators, the change in real GDP might be relatively small while other data indicate a significant decline in economic activity, which is characteristic of recession. The NBER also focuses on monthly assessments of the business cycle, while real GDP is reported quarterly. So, while it’s possible that the economy could experience two quarters of negative real GDP growth and not have a recession, history shows there is a lot of overlap. In each of the past 10 times the economy shrank for two consecutive quarters, a recession resulted. However, there have been recessions where the economy did not contract for two quarters; the 2020 COVID-19 recession lasted only two months, and real GDP declined in only one quarter during the 1980, 1991, and 2001 recessions (Table 2).5

How do peaks and troughs line up with contractions and expansions? The first month of a recession is the month following a peak. Table 3 notes that the business cycle peaked in February 2020, which means the COVID-19 recession started in March 2020. That recession ended in April 2020, the date of the trough.6 The next expansion began in May 2020.

You’ll hear people arguing about whether we’re in a recession because the NBER doesn’t often declare a recession until well after it has begun: The NBER uses data that are backward looking, so it takes time for the NBER to analyze all the data and make a judgment. Sometimes it doesn’t make the call until after a recession has already ended. For example, the recessions of 1991 and 2020 were both relatively short and had already ended by the time the NBER announced the beginning date of the recession. Likewise, the economy is often well into the next expansion by the time the NBER calls the end of the last recession. For example, the NBER made the announcement that the COVID-19 recession ended April 2020 on July 19, 2021 (Table 3).

The NBER notes that it has taken between 4 and 21 months after a recession started to declare the recession had started and that “there is no fixed timing rule. We wait long enough so that the existence of a peak or trough is not in doubt, and until we can assign an accurate peak or trough date.”7 Again, in the meantime, you’ll hear lots of discussion about whether the next recession has started.

What Do Recessions Look Like?

While they all start with a shock, every recession is a little different, which makes us think that Mark Twain’s quote that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” also refers to recessions.

So, what does a “typical” recession look like? Recessions usually include the following characteristics:

A. A negative shock such as a financial crisis occurs.

B. Firms reduce investment spending on machinery, equipment, new factories, and new office buildings (physical capital). In fact, typical recessions begin with reduced business investment spending, which is the most volatile component of GDP because businesses can postpone this type of spending.

C. As business investment falls, affecting employment and demand for inputs, consumers reduce spending on new houses and durable goods such as furniture, appliances, and automobiles.

D. As spending declines, firms that produce these products see declining sales and increasing inventories. They decide to cut production levels and lay off some workers.

E. Rising unemployment and falling profits lead to

further declines in spending.

F. Eventually, the declines will end as consumers and businesses reduce debt and increase their ability to spend and as producers lower their prices to reduce inventory.

G. Lower interest rates and resource prices make investment and spending more attractive.

H. Firms take advantage of low interest rates and resource prices by increasing investment spending on capital goods as they anticipate the next expansion.

I. Consumers take advantage of low interest rates by borrowing to spend on new houses and durable goods.

J. The increased demand for products and services increases employment and income, and consumer spending levels rise.

K. As consumer spending increases, businesses increase production and employment.

L. Recession ends, beginning the next expansion.

Conclusion

Like a roller coaster, the business cycle has ups and downs. However, when it comes to the economy, most people prefer a smooth ride with very few dips. It would be much easier to plan and invest for the future if recessions were easy to predict, but they are not. Rather, they are unpredictable and irregular. The NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee acts as the official referee when it comes to business cycles. This group of expert macroeconomists use economic data and their understanding of the economy to determine when recessions start. (See boxed insert, “Which Specific Economic Indicators Does the NBER Use?”) The process takes time, as the stakes are high, so it’s important to get the “call” right.

Notes

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)