All 21 Different Types of Whales: Guide, Pictures And Classification – Outforia

Of all the world’s marine mammals, few are as majestic and powerful as the large cetaceans that we call whales. These incredible creatures can grow to exceptional lengths, dive to the depths of the ocean, and swim for thousands of miles.

But how much do you really know about the different types of whales in our oceans?

In this article, we’re going to introduce you to 21 of the most wonderful types of whales. From the massive blue whale to the elusive Omura’s whale, here’s everything you’ve ever wanted to know about these amazing seafaring animals.

Get ready—it’s going to be a whale of a time!

Mục Lục

How Are Whales Classified?

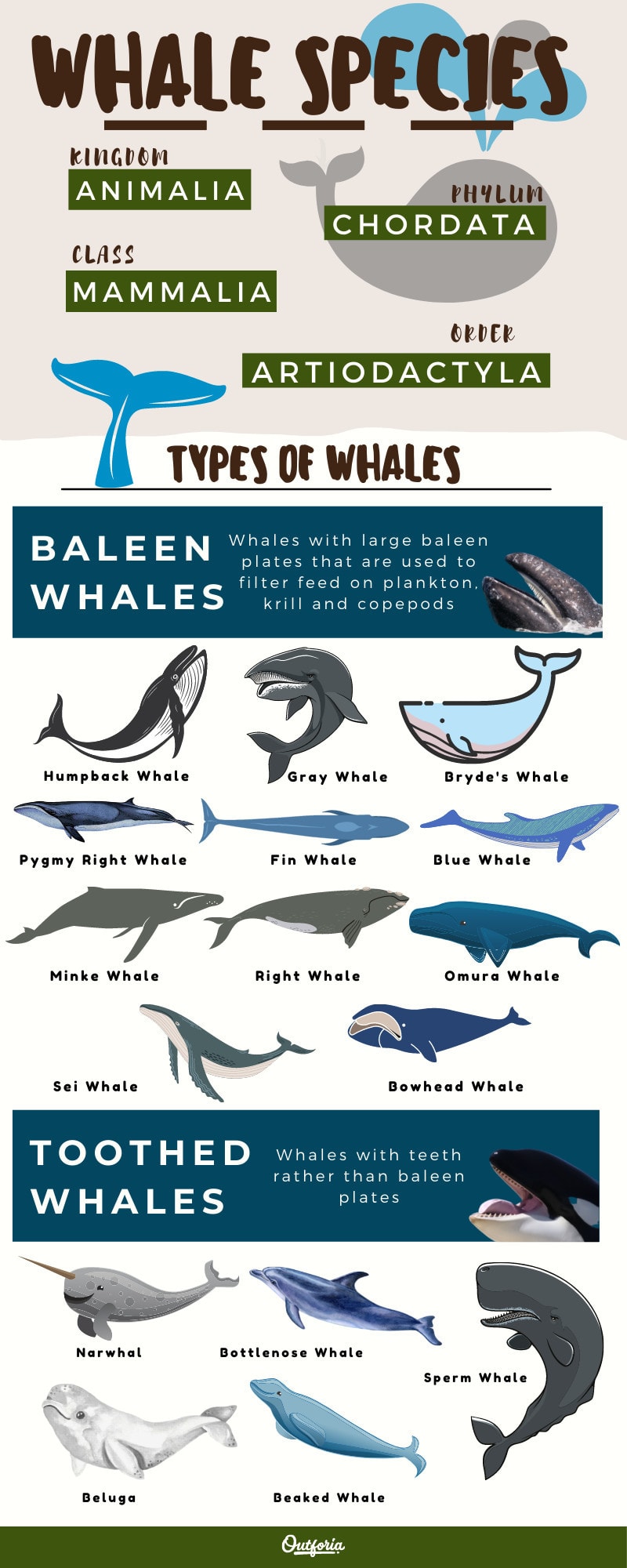

Share This Image On Your Site

<a href="https://outforia.com/types-of-whales"><img style="width:100%;" src="https://outforia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Infographic-Outforia-Types-of-whales-1121.jpg"></a><br> Types of Whales Infographic by <a href="https://outforia.com">Outforia</a>Whales may be some of the most easily recognizable animals on the planet. But they’re notorious among taxonomists for being difficult to classify due to the wide diversity of whales that swim through the Earth’s seas.

All whales are currently classified in the kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, and class Mammalia, which means that whales are mammals. Below the class Mammalia, whales are part of the order Artiodactyla, which includes all the even-toed ungulates.

Wait a minute… ungulates? Aren’t ungulates hoofed animals? How could a whale be an ungulate?

If these thoughts just raced through your brain, we understand. It’s definitely a bit odd to think of whales as ungulates when they don’t have hooves—or feet, for that matter.

But taxonomists have found through genetic analyses that whales evolved from even-toed ungulates (which include animals like antelopes, giraffes, and goats) to be the wonderful marine mammals that we know of today. That means that your average whale has more in common genetically with an alpaca than with a shark. Who knew?

Below the order Artiodactyla, all whales are part of the clade Cetancodonta. This clade includes all the animals that are called cetaceans (this includes whales!) and hippopotamuses. Apparently, hippopotamuses and whales evolved from a common ancestor, so they’re all lumped together into one clade.

Furthermore, within the clade Cetancodonta, all whales are part of the infraorder Cetacea, which includes all the cetaceans. The cetaceans are aquatic mammals that include whales, dolphins, and porpoises.

This is where things start to get a little tricky.

Below the infraorder Cetacea, there are two parvorders: Odontoceti (the toothed whales) and Mysticeti (the baleen whales).

All of the species in the parvorder Mysticeti are considered whales. These include the blue whale, humpback, and other similar large cetaceans with baleen plates for filter feeding. Simple enough, right?

We wish.

The problem is that not all of the species in the parvorder Odontoceti are considered whales in the common use of the term. That’s because Odontoceti also includes the dolphins and porpoises as well as the toothed whales.

Things get even messier when you realize that all dolphins and porpoises are technically whales but that not all whales are dolphins and porpoises. But we’ll leave that taxonomic issue to the scientists to debate.

The thing to remember with whale classification is that the animals that we traditionally call “whales” in the parvorder Odontoceti are primarily found in 3 families/superfamilies:

- Monodontidae – This family is often called the “Arctic whales” and it includes the beluga and narwhal.

- Physeteroidea – The family Physeteroidea includes 3 living whale species: the sperm whale, the pygmy sperm whale, and the dwarf sperm whale.

- Ziphioidea – More commonly known as the beaked whales, many of the species in this superfamily look like larger dolphins with an exceptional ability to dive to deep depths.

If you’ve managed to stay with us to this point—congrats. You’ve made it pretty darn far. But we want to wrap up this quick look at whale classification to remind you that some animals that look like whales are actually better classified as dolphins.

For example, the orca (sometimes called the killer whale) is a dolphin. It’s a large dolphin, to be fair, but a dolphin nonetheless. Other species that are normally referred to as whales, like the pilot whale, are also dolphins. Alas. Such is the life of a whale taxonomist!

You may also like: Discover all the 33 Adorable Seals with Photos, FAQs and Infographics!

Types of Whales FAQs

Here are our answers to some of your most commonly asked questions about the different types of whales:

What are the two main types of whales?

The two main types of whales are the baleen whales and the toothed whales. Baleen whales, like the humpback whale, feature large baleen plates in their mouths that allow them to filter feed for krill and plankton. Meanwhile, toothed whales, such as the sperm whale, have teeth that they use for hunting fish and other larger sea creatures.

How many types of whales are there?

There are approximately 40 types of whales in the ocean. But classifying whales is difficult as some animals that are traditionally called whales might better be classified as dolphins (a subset of whales).

Is a whale shark a whale or a shark?

Despite its confusing name, a whale shark is a type of shark. It is a fish, like all sharks, not a mammal, like a whale. However, whale sharks are similar to baleen whales because they’re filter feeders that primarily eat krill, plankton, and other copepods.

How old do whales live?

All whale species have different lifespans, but most can live for about 50 to 100 years. The oldest-living whale, however, is likely the bowhead whale. Researchers believe that the bowhead whale can live for more than 200 years!

Can a whale swallow a human?

Most whales aren’t capable of fully swallowing a human because their esophagus isn’t wide enough for a human body. But baleen whales have scooped up humans in their mouths before, only to spit them out a few minutes later. That certainly wouldn’t be a pleasant experience, but it’s not exactly the same as getting swallowed by a whale.

21 Different Types of Whales: List and Pictures

There are dozens of different types of whales swimming through our planet’s oceans, so we couldn’t possibly list them all here. But, here’s a quick look at 21 of the most incredible types of whales on Earth!

1. Baleen Whales

Baleen whales are a grouping of whales that all boast large baleen plates that they use to filter feed on plankton, krill, and copepods. These whales are among the largest animals on the planet and they’re a true wonder to behold if you ever get to see them in the wild. Here’s what you need to know.

1.1 Bowhead Whale

Found only in the Arctic and subarctic, the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) is a mid-sized cetacean with one of the world’s longest lifespans. Although the bowhead whale has long been hunted by humans, when allowed to live out the course of its natural lifespan, this species can live to be more than 200 years old!

Bowhead whales have a distinctive shape and build that makes them easy to identify in their home range. While many whale species have large mouths, the bowhead has the largest mouth of any animal. In fact, its mouth can be around 16 feet (5 m) long and its tongue normally weighs around 1 ton (900 kg).

Despite the fact that the bowhead was nearly hunted to extinction during the height of the global whaling industry, a moratorium on hunting the bowhead in the 1960s has allowed the species to make a remarkable recovery. Globally, the species is now listed as being of least concern by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

1.2 Southern Right Whale

One of the three species of right whale, the southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) is a cetacean that’s found only in waters between 20ºS and 60ºS. It is nearly identical to the other right whales, but it is easily identifiable from other whales in its range thanks to its black body and the large gray callosities on its head.

Although they aren’t particularly common, southern right whales tend to be quite active near the surface of the water. They’re also fairly curious around vessels, so they are likely to interact with ships and boats during sightings.

Southern right whales were heavily hunted in the nineteenth century after the depletion of the North Atlantic right whale population during the eighteenth century. However, the harpooning of southern right whales was banned by the mid-twentieth century and it’s now protected in many areas. The species’ population has stabilized and it’s now listed as a species of least concern.

1.3 North Atlantic Right Whale

The northern cousin of the southern right whale, the North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) is a cetacean that lives only in the temperate and sub-Arctic waters of the northern Atlantic Ocean.

Like other right whales, the North Atlantic right whale is a slow-moving, docile cetacean that spends a lot of time near the surface. It’s often spotted near the coast, and many individual North Atlantic right whales get tangled up in fishing gear each year.

During the eighteenth century, the North Atlantic right whale was nearly driven to extinction by commercial whalers. It is now protected in many jurisdictions, but researchers believe it may be functionally extinct in the eastern North Atlantic. Throughout its range, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the North Atlantic right whale as critically endangered.

1.4 North Pacific Right Whale

The North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) is the last of the three right whale species. It lives only in the northern Pacific, mostly in the near-coastal areas around Alaska, western Russia, and Japan.

Due to the remoteness of its range and its relatively small population numbers, the North Pacific right whale is rarely spotted by vessels. This makes tracking and observing North Pacific right whales very challenging for researchers.

Commercial whaling of the North Pacific right whale began in the 1830s and nearly caused the extinction of the species before it was protected in the 1960s. Nowadays, its main threats are oil spills, fishing gear entanglement, illegal whaling, and hybridization with bowhead whales. The species is listed as endangered by the IUCN.

1.5 Pygmy Right Whale

Lycaon.cl / CC BY 3.0 / Wikimedia commons

Lycaon.cl / CC BY 3.0 / Wikimedia commons

Although it shares a similar name to the other right whales, the pygmy right whale (Caperea marginata) is a distinct species that’s the only member of the family Neobalaenidae. It was actually thought to be extinct until 2012 due to a lack of confirmed sightings.

The pygmy right whale lives primarily in the Southern Ocean. It was first described in scientific

Literature after James Clark Ross’ nineteenth-century voyages on the HMS Erebus and Terror. However, it is among the least studied cetaceans in the world with fewer than 25 confirmed sightings.

With an estimated length of about 20 feet (6.1 m), the pygmy right whale is the smallest of the known baleen whales. The IUCN currently lists it as a species of least concern, but this may be due to a lack of data than anything else.

1.5 Common Minke Whale

Sometimes called the northern minke whale, the common minke (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) is a small baleen whale that lives in nearly all the world’s oceans. Technically, there are multiple common minke subspecies and only the dwarf subspecies is commonly sighted in the Southern Ocean.

The common minke is one of the smallest baleen whale species. It’s relatively easy to identify throughout its range due to its small curved dorsal fin. Additionally, the species has a unique surfacing sequence where it first brings its pointed rostrum to the surface and then arches its back before diving. Most minkes breathe multiple times in rapid succession before a deep dive.

Globally, the common minke is listed as a species of least concern by the IUCN. It is protected in many regions after being heavily hunted during the height of the commercial whaling industry in the eighteenth through twentieth centuries.

1.6 Southern Minke Whale

More commonly known as the Antarctic minke whale, the southern minke (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) is slightly larger than the common minke. Although its range overlaps with the dwarf subspecies of common minke, the Antarctic minke is generally only found in the southern hemisphere and it is much more abundant in its range.

Unlike many other baleen whales, the southern minke wasn’t heavily hunted by commercial whalers. It has a smaller size and a relatively low oil yield, so it wasn’t as economically attractive as other species. As a result, it is now much more prevalent than its northern counterpart.

Nevertheless, the IUCN lists the southern minke as near threatened. The organization states that the species’ primary threats are overfishing of krill in its range and climate change.

1.7 Gray Whale

Found only in small near-coastal areas around the world, the gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) is a large cetacean that can reach a weight of upwards of 45 tons (40,820 kg). The gray whale used to be much more widely distributed, but it was extirpated around Europe sometime during the sixth century and around the eastern Atlantic around the eighteenth century.

One of the more unique aspects of the gray whale is its long seasonal migratory route. Each population of gray whales travels to different areas, but the eastern Pacific population travels approximately 5,000 miles (8,000 mi) from the Bering and Chukchi seas to the Gulf of California each winter season. This is believed to be the longest annual migration of any mammal.

Although orcas are known to hunt gray whales, commercial whaling by humans is arguably the species’ biggest threat. Now that the species is no longer commercially hunted on a large scale, it’s now listed as being of least concern by the IUCN.

1.8 Humpback Whale

Arguably the most iconic whale species in the world, the humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae) is one of few large cetaceans that’s found in nearly all of Earth’s oceans. It’s found everywhere from tropical areas to the frigid waters of the polar regions.

Humpback whales are perhaps best known for their acrobatic surfacing behaviors and amazing communication skills. Male humpbacks produce complex songs that can last for around 20 minutes at a time. Female humpbacks vocalize, too, but they don’t produce noises of the same complexity. Researchers believe these songs are unique to different populations of humpbacks.

Like other baleen whales, humpbacks were targeted by commercial whalers for centuries until the 1960s. During the commercial whaling period, humpbacks were nearly driven to extinction. Researchers estimate that over 90% of the global population of humpbacks was killed. However, the species has made an exceptional recovery and is now of least concern.

1.9 Blue Whale

The largest known animal to have ever existed on this Earth, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is a truly magnificent cetacean. It can reach lengths of about 98 feet (29.9 m) and weigh upwards of 165 tons (150,000 kg).

Despite being the biggest animal in the world, blue whales feed on some of the smallest animals—krill. In fact, blue whales eat upward of about 8,000 lbs (3,600 kg) of krill in a single day!

Blue whales are believed to live in nearly all of the world’s oceans. They were once very abundant but the species was hunted to near extinction during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It remains one of the least-studied baleen whales and the IUCN currently lists the blue whale as endangered.

1.10 Fin Whale

Aqqa Rosing-Asvid / CC BY 2.0 / Wikimedia commons

Aqqa Rosing-Asvid / CC BY 2.0 / Wikimedia commons

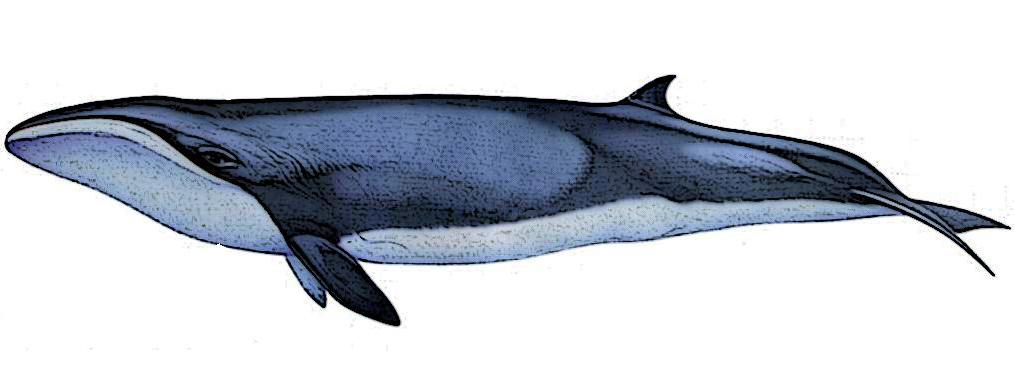

Often called the finback whale, the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) is the second-longest cetacean on the planet. It can be upward of 90 feet (27 m) long but it usually weighs around 80 tons (72,500 kg) or less.

Fin whales are found in nearly all of the world’s oceans. However, they are fairly easy to identify when compared to other large whales due to their tall spout and prominent dorsal fin. That said, it’s sometimes easy to confuse with blue and sei whales from afar.

Like blue whales, fin whales were heavily hunted by whalers, particularly after the invention of the explosive harpoon. During the height of the commercial whaling industry, approximately 50% of all fin whales were hunted for their blubber, baleen, and oil. The species is now listed as vulnerable with an increasing population.

1.11 Omura’s Whale

Salvatore Cerchio et al. / Royal Society Open Science / CC BY 4.0 / wikimedia commons

Salvatore Cerchio et al. / Royal Society Open Science / CC BY 4.0 / wikimedia commons

The Omura’s whale (Balaenoptera omurai) is one of the least-studied species of large baleen whales. It’s also known as the dwarf fin whale, but it was long believed to be a smaller or pygmy form of the Bryde’s whale.

Researchers believe that Omura’s whales are found in the Indo-Pacific Ocean but that there may also be a population in the Atlantic. There have been a number of confirmed Omura’s whale sightings in the past, but not enough to get a good idea of the species’ true range.

It’s very likely that the Omura’s whale was hunted throughout Oceania for sustenance purposes during the last few millennia, but it’s never been the target of widespread commercial whaling. The IUCN currently lists the species as data deficient due to a lack of research on its population trends.

1.12 Eden’s Whale

Eden’s whales (Balaenoptera edeni) are a debated baleen whale species that’s part of the Bryde’s whale complex. The three species in the Bryde’s whale complex (Rice’s, Eden’s, and Bryde’s whales) share similar physical characteristics but more research is needed to understand how they’re all related.

Researchers believe that Eden’s whales live primarily in the western Pacific around the Bay of Bengal, the Gulf of Martaban, and the East China Sea. The Eden’s whale, which is sometimes called the Sittang whale, is believed to be the smallest of the species in the Bryde’s whale complex.

Little is known about the global population of the Eden’s whale, but the IUCN lists it as a species of least concern. The species’ main threats include collisions with ships, pollution, and the depletion of its food source by commercial krill fishing.

1.13 Rice’s Whale

The Rice’s whale (Balaenoptera ricei) is one of the better-studied members of the Bryde’s whale complex. It was previously thought to be a subpopulation of Bryde’s whale, but recent genetic analyses show that it is likely a distinct species.

Unlike most other Bryde’s whales, the Rice’s whale lives almost exclusively in the Gulf of Mexico. It lives primarily around the continental slope of the northern part of the Gulf near Florida.

The Rice’s whale isn’t currently listed by the IUCN (likely due to the fact that it was designated as a unique species in 2021). But it is listed as endangered under the US Endangered Species Act and it is protected in its range. The species’ primary threats include vessel collisions, pollution, and acoustic disturbances from shipping and oil exploration.

1.14 Sei Whale

Christin Khan / Public Domain / wikimedia commons

Christin Khan / Public Domain / wikimedia commons

Found primarily offshore in areas of deep water, the sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) is the planet’s third-largest cetacean. It generally avoids both polar and tropical waters, preferring to spend its time in temperate and subtropical areas. However, researchers believe that the sei whale can live nearly anywhere on Earth.

Sei whales are considered to be one of the fastest cetaceans. They can reach swimming speeds of over 31 mph (50 km/h) when traveling short distances. The sei whale is also a truly massive marine mammal with an average weight of up to 50 tons (45,400 kg).

The sei whale’s large size made it a popular choice for hunting during the heyday of commercial whaling. As a result, the species’ population is believed to be only one-third of what it was in the sixteenth century. It’s currently listed as endangered with an increasing population.

1.15 Common Bryde’s Whale

The common Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera brydei) is the largest cetacean in the Bryde’s whale species complex. There’s some debate among taxonomists over whether the common Bryde’s whale is its own species or if it’s a subspecies that’s closely related to the Eden’s whale.

These whales are primarily found in the warmer temperate and tropical waters of the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. The common Bryde’s whale is pelagic, which means that it prefers to live primarily in the open ocean.

Relatively little is known about the population trends of the common Bryde’s whale. This is partly a result of the fact that taxonomists don’t know how to classify this species. However, the Bryde’s whale is known to be sensitive to disturbances and its major threats include vessel strikes on the open ocean.

2. Toothed Whales

Aptly named, the toothed whales are a distinct grouping of whales, all of which feature teeth, rather than baleen plates. Toothed whales, which are also known as odontocetes, are part of a parvorder of cetaceans that also includes porpoises and dolphins

There are more than 70 species within the parvorder Odontoceti, most of which are different types of dolphins and porpoises. Many of the animals in this parvorder that we normally think of as whales, such as orcas, are better classified as dolphins.

In the interest of keeping things fresh and exciting, we’ll focus on 6 of the toothed whales that are generally classified by taxonomists as being true whales. Without further ado, here’s a quick look at some of the coolest toothed whales in our oceans.

2.1 Sperm Whale

Easily the largest of the toothed whales, the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) is a truly massive cetacean. It’s the only living member of its genus and it’s considered to be the largest toothed predator on the planet.

Sperm whales became famous in popular culture thanks to Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick. In the novel, a giant white sperm whale named Moby Dick bit off Captain Ahab’s leg while he sailed on the whaling ship Pequod.

The name “sperm whale” might seem a little odd, but it’s actually an abbreviated version of the proper name “spermaceti whale.” Spermaceti is a waxy, semi-liquid substance that’s found in the melon (forehead) of a sperm whale’s head. This substance is believed to help generate clicking sounds for communication and echolocation.

This spermaceti was actually the primary target of commercial whalers in the eighteenth through twentieth centuries. It was used to create candles and other similar products. Whalers also sought out the sperm whale’s teeth, which have an ivory-like quality. However, hunting of the sperm whale decimated its population and the species is now listed as vulnerable.

2.2 Narwhal

Also known as the unicorn of the sea, the narwhal (Monodon monoceros) is one of the most easily identifiable cetaceans in the world. Male narwhals (and a select few female narwhals) boast a single large tusk-like protrusion from the front of their heads that can grow to be around 10 feet (3.1 m) long. In rare instances, narwhals can grow two tusks.

This tusk is actually the narwhal’s canine tooth—not a horn. It projects outward from the left side of the narwhal’s upper jaw and grows in a helical spiral throughout the whale’s life. In fact, new research shows that narwhal tusks are filled with millions of nerve endings that provide narwhals with sensory information about their environment.

Narwhals are found only in Arctic waters where they have been hunted for sustenance for thousands of years by the Inuit and other Indigenous peoples. The Inuit are allowed to legally hunt narwhal for cultural and subsistence purposes. The IUCN lists the species as being of least concern, though climate change and changing sea ice conditions are major threats.

2.3 Southern Bottlenose Whale

Vacanze in USA, Florida

Vacanze in USA, Florida

The southern bottlenose whale (Hyperoodon planifrons) is a poorly researched cetacean that lives in the Antarctic. Scientists believe that it primarily inhabits deep ocean waters in the coldest parts of the Southern Ocean. The species is also believed to be able to dive for up to 40 minutes at a time, which is a long time for a cetacean.

Southern bottlenose whales are a type of beaked whale and they feature a small “beak” that’s similar to what we see on many dolphins. Researchers think that the southern bottlenose is primarily white and gray in color, but more information is needed to understand the spectrum of the species coloration and appearance variations.

Currently, the IUCN lists the southern bottlenose whale as a species of least concern. However, there aren’t any good estimates of the species’ population and little is known about the threats that it faces.

2.4 Beluga

Also called the white whale, the beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) is one of the most easily identifiable cetaceans on the planet. It has an all-white body and a large, melon-shaped head. This makes it easy to distinguish from every other cetacean of its size, including the narwhal, which is the beluga’s closest living relative.

The beluga is also known as the sea canary because it makes distinctive high-pitched sounds. These sounds are used for echolocation and communication in dark waters. A beluga’s melon is actually an essential part of its communication abilities because the melon acts as an acoustic lens that can help project its calls over longer distances.

Belugas are currently listed as being of least concern by the IUCN. However, they face a number of threats including climate change, which negatively affects the species’ Arctic habitat. Belugas also appear to be very sensitive to human noise and to ocean pollution.

2.5 Baird’s Beaked Whale

The Baird’s beaked whale (Berardius bairdii) is a relatively well-studied beaked whale species. It primarily lives in the northern Pacific, particularly in deep water environments.

However, there is some debate over whether Baird’s beaked whales and Arnoux’s beaked whales are the same species due to their similar characteristics. If they are the same species, then the Baird’s whale’s range would include much of the Southern Ocean.

Baird’s beaked whales are known for their large size and their shyness around boats. They tend to have darker colorations than other beaked whales, but more research is needed to understand the species’ true range of appearances. The species is protected in the United States but it is currently listed as a species of least concern by the IUCN.

2.6 Cuvier’s Beaked Whale

Last but not least, we have the Cuvier’s beaked whale (Ziphius cavirostris). The Cuvier’s beaked whale is believed to be the most widely distributed beak whale on the planet. It lives in nearly all the world’s oceans except in the extreme polar regions.

Cuvier’s beaked whales have a dark coloration, small beak, and a cigar-shaped body. Males sometimes develop two small tusks in the corners of their lower jaw, but these tusks don’t seem to serve any purpose.

Like most beaked whales, Cuvier’s beaked whales are expert divers and they can dive for hours at a time. In fact, researchers once tagged a whale that made a recorded dive of over 9,800 feet (2,900 m), which is one of the deepest dives ever recorded by a mammal!

Cuvier’s beaked whales were hunted in modest numbers by commercial whalers, but the species’ biggest threat is likely human disturbance. The species seems to be very sensitive to sonar, which may be the reason why they’re often found stranded on beaches in noisy areas like the Mediterranean and around naval bases.

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)