Vietnam’s vibrant social enterprise sector has more to give

The social enterprise sector in Vietnam is diverse, vibrant and growing – and optimistic about the future. But a new report, Social Enterprise in Vietnam, published in March by the British Council highlights that five years after the term ‘social enterprise’ gained legal recognition in the country, the development of the sector hasn’t been as rapid as many had hoped and big challenges remain.

Writing in the Foreword to the report, Dr Nguyen Dinh Cung, president of enterprise support body the Central Institute for Economic Management, said: “Before 2012, the term social enterprise attracted little attention in Vietnam. It was not until 2014 that the term social enterprise was officially recognised as a distinct type of organisation in Vietnam’s Enterprise Law, thereby paving the way for a more developed ecosystem of social enterprise support.

Writing in the Foreword to the report, Dr Nguyen Dinh Cung, president of enterprise support body the Central Institute for Economic Management, said: “Before 2012, the term social enterprise attracted little attention in Vietnam. It was not until 2014 that the term social enterprise was officially recognised as a distinct type of organisation in Vietnam’s Enterprise Law, thereby paving the way for a more developed ecosystem of social enterprise support.

“However, five years on, the development of the social enterprise sector has been more modest than some would have hoped. Social enterprises can face many challenges and difficulties, such as lack of funds, skills, technology, land and information. In addition, the government’s policies need further improvement.”

The report was launched on 22 March in Hanoi, alongside a BuySocial Fair which showcased local social enterprises.

Stuffed toys on display at the BuySocial Fair from Morning Star (Sao Mai) Center , a social enterprise which provides support for children with learning disabilities and autism

The Enterprise Law, which came into practice in 2015, recognised a social enterprise as “an enterprise that is registered and operates to resolve a or a number of social and environmental issues for a social purpose; and reinvests at least 51 percent of total profits to resolve the registered social and environmental issues.”

This, the report says, was an important milestone and followed work to develop social enterprise in Vietnam, initially through universities, by the British Council and other international organisations.

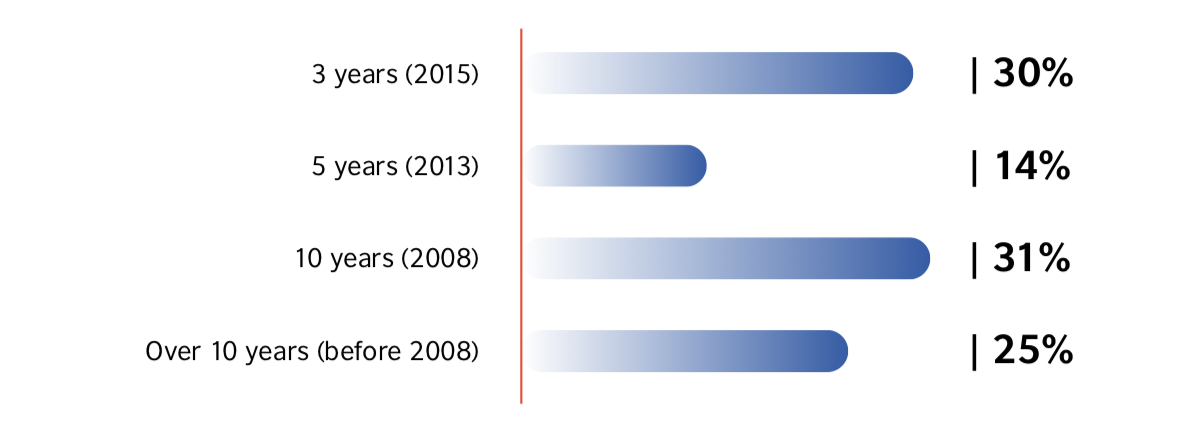

Since the law was passed, 30% of Vietnam’s 19,000 social enterprises have been formed, the report found. This “new wave” of social enterprises, as the report calls them, have young, educated leaders and are focused on helping particular communities and creating employment.

Vietnam’s new wave of social enterprises began to develop in 2015

Following the passing of the law, two further landmark events helped the development of social enterprise in the country, according to both the report and Pham Kieu Oanh, founder of the Centre for Social Initiatives Promotion (CSIP), a longstanding supporter.

“In 2015, when the UN launched the SDGs, there was movement to engage the business sector to address social challenges. The concept of impact enterprise or social business got a lot more attention in Vietnam,” says Oanh, speaking on the phone from Hanoi.

The Vietnamese government then declared a ‘Start-up Nation’ campaign in 2016. Looking to encourage their number, the government offered lower taxes to SMEs and encouraged banks to lend to them by offering credit guarantees. Carrots were also dangled to larger companies with 80% of SMEs in their supply chain in the shape of reduced land rents and reduced corporate income tax.

Additionally, social enterprises were promised investment incentives and allowed to receive foreign non-governmental aid to resolve social and environmental issues. But if an organisation registers with the government as a social enterprise, grants can be liable for corporate tax.

Vietnam’s development

Vietnam is a rapidly developing south-east Asian country – one of the most dynamic in the region. The World Bank’s view is that economic and political reforms since 1986 have transformed the country from one of the world’s poorest nations to a lower-middle income country. Increased prosperity has coincided with an increase in numbers, with the population enlarging by 50% in the same period to about 95 million in 2017.

However, Vietnam continues to face social challenges such as poverty, unequal access to public health and education, and the need for environmental sustainability.

Improving a particular community was a popular objective for the social enterprises surveyed, with local people and ethnic minorities being a particular focus. Those with physical or learning disabilities, the long term unemployed and older people also figured highly amongst beneficiaries identified by those surveyed.

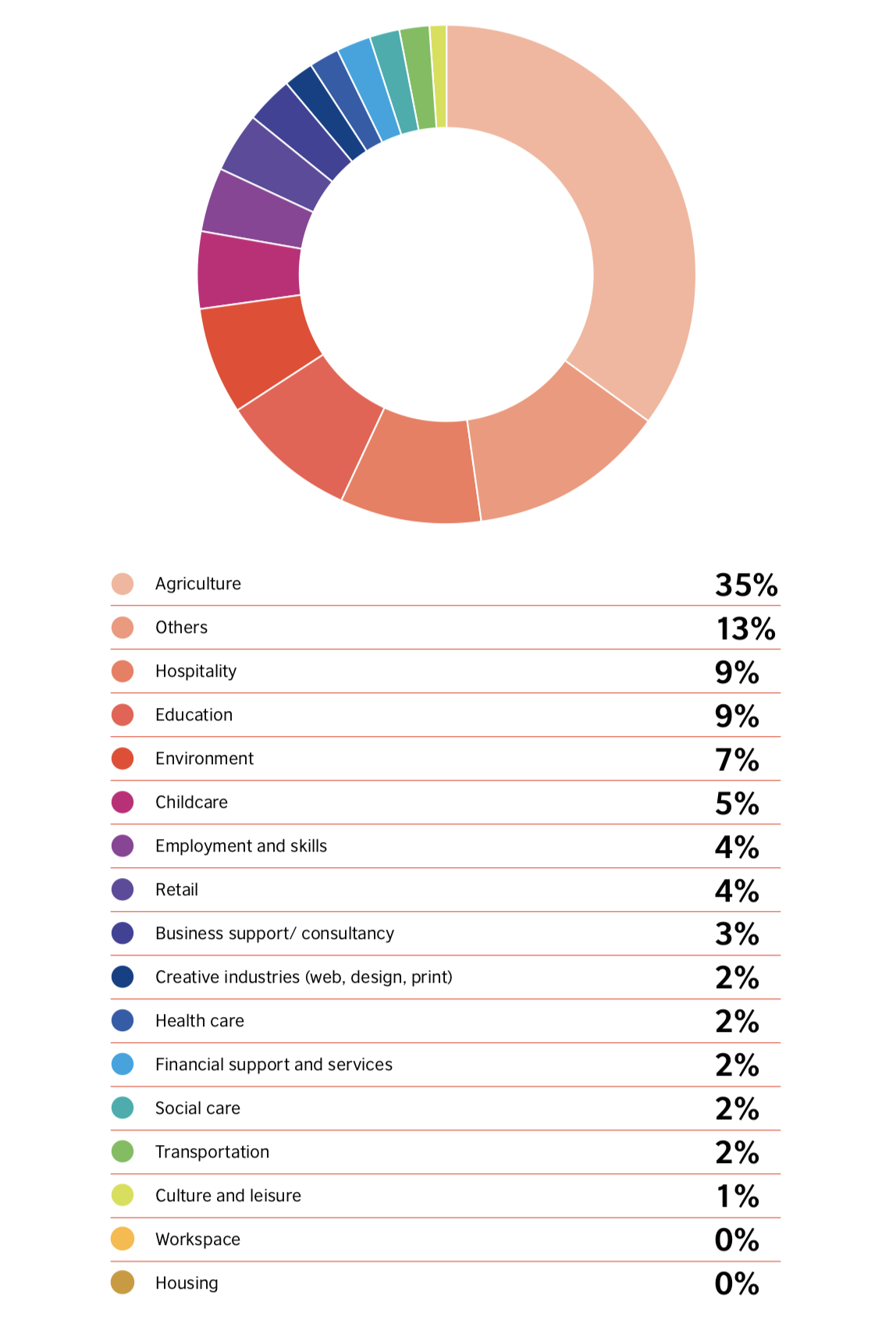

In surveying 142 of them, agriculture is the sector that a majority of social enterprises are working in, accounting for 35% of respondents. This is perhaps no surprise given that agriculture contributes a quarter of the country’s GDP, employs over 70% of the population and 90% of the poor living in rural areas, according to the Overseas Development Institute.

Agriculture is the most prevalent sector for social enterprises’ work in Vietnam

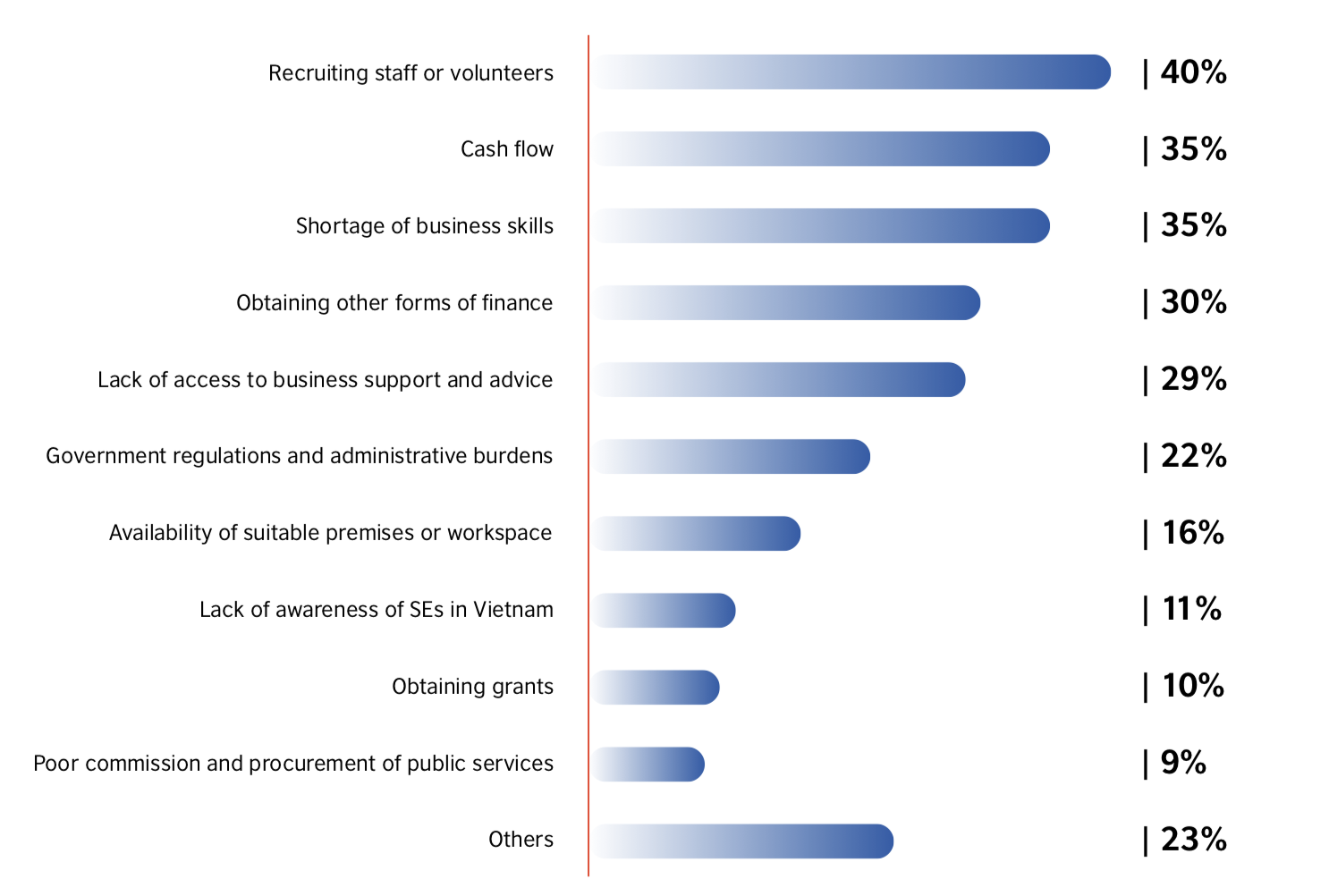

Donations remain the most common form of funding for social enterprises and a reluctance to access finance is perhaps indicative of the business skills that organisations reported being short of. A lack of measurement of their social impact was also hindering them when trying to access investment, the report found.

Alongside a shortage of business skills, cashflow and recruitment of staff topped the list of reasons reported by survey respondents as barriers to growth. It suggests the social enterprises themselves are aware they might be missing out on opportunities due to an inability to secure the right talent for their organisations.

Barriers to growth in Vietnam include finding the right talent

The ‘start up nation’ gives job seekers plenty of options, thinks Oanh, with social enterprise not perceived to offer the stability, salary or benefits that mainstream, purely commercial business offers.

Of the organisations surveyed, 38% saw themselves as social enterprises, with others opting to see themselves as commercial businesses, co-operatives or something else: 20% chose the ‘Other’ option.

The report concludes that social enterprises should be supported to make better use of the existing support available to them. It highlights that stakeholders should do more to spread understanding of social enterprise. And it suggests the government should consider how social enterprises could be given more preferential treatment in procurement and commissioning. Finally, it calls for the government to improve some aspects of how the Enterprise Law is implemented.

Above: Ms Ha Nguyen from Oxfam Vietnam explores cinnamon and star anise products from social enterprise Vina Samex at the BuySocial Fair

Oanh says she wants to see collaboration between the sector and the government to achieve a clear direction for the continuing development of social enterprise in the country.

“I don’t think only government should lead it. It should be co-creation with the participation of different stakeholders to agree on the concrete agenda on social enterprise for the next five years.”

Header photo: HAPI Vegan staff show off their products – dried fruits, ground peanuts and mushroom floss – at the BuySocial Fair in Hanoi in March

• Interested in global social enterprise research? Check out our coverage of the British Council’s extensive collection of reports here.

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)