The Hard Truth About Business Model Innovation

Surveying the landscape of recent attempts at business model innovation, one could be forgiven for believing that success is essentially random. For example, conventional wisdom would suggest that Google Inc., with its Midas touch for innovation, might be more likely to succeed in its business model innovation efforts than a traditional, older, industrial company like the automaker Daimler AG. But that’s not always the case. Google+, which Google launched in 2011, has failed to gain traction as a social network, while at this writing Daimler is building a promising new venture, car2go, which has become one of the world’s leading car-sharing businesses. Are those surprising outcomes simply anomalies, or could they have been predicted?

To our eyes, the landscape of failed attempts at business model innovation is crowded — and becoming more so — as management teams at established companies mount both offensive and defensive initiatives involving new business models. A venture capitalist who advises large financial services companies on strategy shared his observation about the anxiety his investors feel about the changes underway in their industry: “They look at the fintech [financial technology] startups and see their business models being unbundled and attacked at every point in the value chain.” And financial services companies are not alone. A PwC survey published in 2015 revealed that 54% of CEOs worldwide were concerned about new competitors entering their market, and an equal percentage said they had either begun to compete in nontraditional markets themselves or considered doing so.1 For its part, the Boston Consulting Group reports that in a 2014 survey of 1,500 senior executives, 94% stated that their companies had attempted some degree of business model innovation.2

We’ve decided to wade in at this juncture because business model innovation is too important to be left to random chance and guesswork. Executed correctly, it has the ability to make companies resilient in the face of change and to create growth unbounded by the limits of existing businesses. Further, we have seen businesses overcome other management problems that resulted in high failure rates. For example, if you bought a car in the United States in the 1970s, there was a very real possibility that you would get a “lemon.” Some cars were inexplicably afflicted by problem after problem, to the point that it was accepted that such lemons were a natural consequence of inherent randomness in manufacturing. But management expert W. Edwards Deming demonstrated that manufacturing doesn’t have to be random, and, having incorporated his insights in the 1980s, the major automotive companies have made lemons a memory of a bygone era. To our eyes, there are currently a lot of lemons being produced by the business model innovation process — but it doesn’t have to be that way.

In our experience, when the business world encounters an intractable management problem, it’s a sign that business executives and scholars are getting something wrong — that there isn’t yet a satisfactory theory for what’s causing the problem, and under what circumstances it can be overcome. This is what has resulted in so much wasted time and effort in attempts at corporate renewal. And this confusion has spawned a welter of well-meaning but ultimately misguided advice, ranging from prescriptions to innovate only close to the core business to assertions about the type of leader who is able to pull off business model transformations, or the capabilities a business requires to achieve successful business model innovation.

The hard truth about business model innovation is that it is not the attributes of the innovator that principally drive success or failure, but rather the nature of the innovation being attempted. Business models develop through predictable stages over time — and executives need to understand the priorities associated with each business model stage. Business leaders then need to evaluate whether or not a business model innovation they are considering is consistent with the current priorities of their existing business model. This analysis matters greatly, as it drives a whole host of decisions about where the new initiative should be housed, how its performance should be measured, and how the resources and processes at work in the company will either support it or extinguish it.

Mục Lục

About the Research

This article assembles knowledge that the primary author has developed over the course of two decades studying what causes good businesses to fail, complemented by a two-year intensive research project to uncover where current managers and leadership teams stumble in executing business model innovation. Over the course of the past two years of in-depth study, we evaluated 26 business model innovations in the historical record that had run a course from idea to development to success, or failure. The study identified 10 failures and 16 successes and coded each across 20 dimensions to identify patterns associated with success and failure.

To further develop our understanding of the causality behind the relationships we observed, we also assembled a cohort of nine market-leading companies from industries as diverse as information technology, consumer products, travel and leisure, fashion, publishing, and financial services. Each of these companies is attempting to execute some degree of business model innovation. We observed these companies as they undertook their business model innovation efforts and conducted interviews with more than 60 C-level executives across the nine companies. In addition to our interviews, we convened two working sessions at Harvard Business School that brought executives from each company together to discuss the challenges, opportunities, and realities of business model innovation from the perspective of the manager.

This truth has revealed itself to us gradually over time, but our thinking has crystallized over the past two years in an intensive study effort we have led at the Harvard Business School. As part of that research effort, we have analyzed 26 cases of both successful and failed business model innovation; in addition, we have selected a set of nine industry-leading companies whose senior leaders are currently struggling with the issue of conceiving and sustaining success in business model innovation. (See “About the Research.”) We have profiled these nine companies’ efforts extensively, documented their successes and failures, and convened their executives on campus periodically to enable them to share insights and frustrations with each other. Stepping back, we’ve made a number of observations that we hope will prove generally helpful, and we also have a sense of the work that remains to be done.

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Privacy Policy

There are a number of lessons that managers can learn from past successes and failures, but all depend on understanding the rules that govern business model formation and development — how new models are created and how they evolve across time, the kinds of changes that are possible to those models at various stages of development, and what that means for organizational renewal and growth.

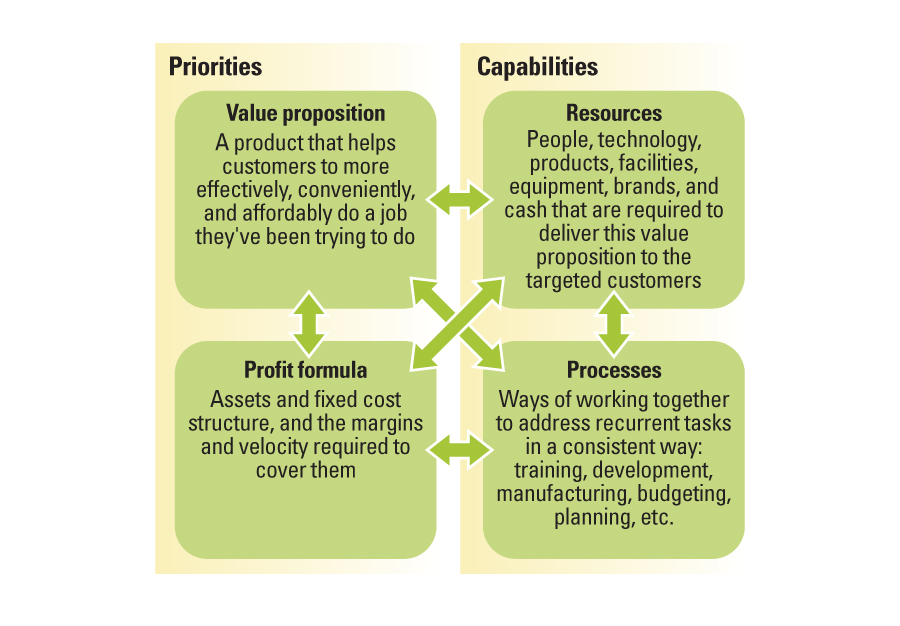

The Business Model’s Journey

The confusion surrounding business model innovation begins, appropriately enough, with confusion about the term “business model.” In our course at the Harvard Business School, we teach students to use a four-box business model framework that we developed with colleagues from the consulting firm Innosight LLC. This framework consists of the value proposition for customers (which we will refer to as the “job to be done”); the organization’s resources, such as people, cash, and technology; the processes3 that it uses to convert inputs to finished products or services; and the profit formula that dictates the margins, asset velocity, and scale required to achieve an attractive return.4 (See “The Elements of a Business Model.”) Collectively, the organization’s resources and processes define its capabilities — how it does things — while its customer value proposition and profit formula characterize its priorities — what it does, and why.5

The Elements of a Business Model

This way of viewing business models is useful for two reasons. First, it supplies a common language and framework to understand the capabilities of a business. Second, it highlights the interdependencies among elements and illuminates what a business is incapable of doing. Interdependencies describe the integration required between individual elements of the business model — each component of the model must be congruent with the others. They explain why, for example, Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Ltd. is unable to sell cheap bespoke cars and why Wal-Mart Stores Inc. is unable to combine low prices with fancy stores.

Understanding the interdependencies in a business model is important because those interdependencies grow and harden across time, creating another fundamental truth that is critical for leaders to understand: Business models by their very nature are designed not to change, and they become less flexible and more resistant to change as they develop over time. Leaders of the world’s best businesses should take special note, because the better your business model performs at its assigned task, the more interdependent and less capable of change it likely is. The strengthening of these interdependencies is not an intentional act by managers; rather, it comes from the emergence of processes that arise as the natural, collective response to recurrent activities. The longer a business unit exists, the more often it will confront similar problems and the more ingrained its approaches to solving those problems will become. We often refer to these ingrained approaches as a business’s “culture.”6

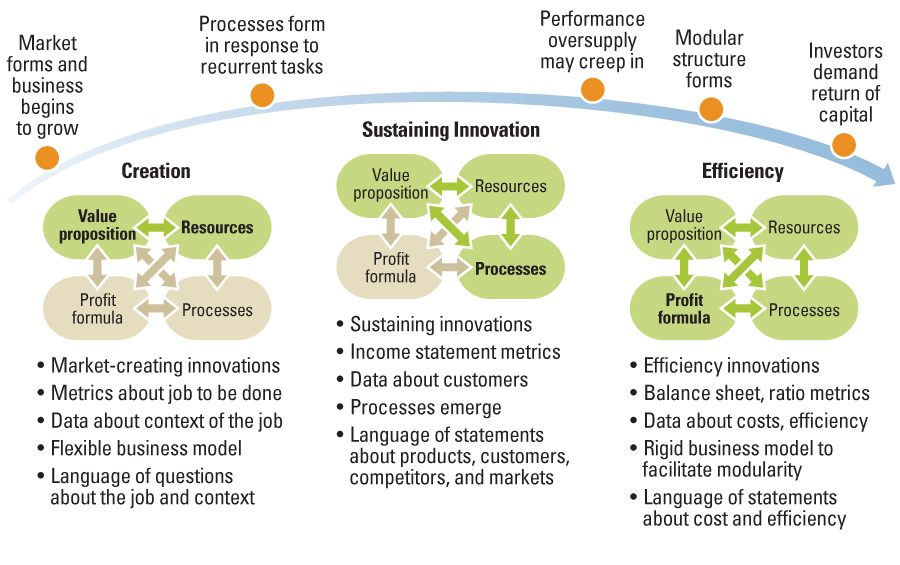

In fact, this pattern is so consistent and important that we’ve begun to think of the development of a business model across time as resembling a journey whose progress and route are predictable — although the time that it takes a business model to follow this journey will differ by industry and circumstance. (See “The Three Stages of a Business Model’s Journey.”) As the diagram depicts, a business model, which in an established company is typically embodied in a business unit,7 travels a one-way journey, beginning with the creation of the new business unit and its business model, then shifting to sustaining and growing the business unit, and ultimately moving to wringing efficiency from it. Each stage of the journey supports a specific type of innovation, builds a particular set of interdependencies into the model, and is responsive to a particular set of performance metrics. This is the arc of the journey of virtually every business model — if it is lucky and successful enough to travel the entire length of the route. Unsuccessful business units will falter before concluding the journey and be absorbed or shuttered. Now, let’s explore each of the three stages and how the business model evolves through them.

The Three Stages of a Business Model’s Journey

1. Creation

Peter Drucker once said that the purpose of a business is to create a customer.8 That goal characterizes the first stage of the journey, when the business searches for a meaningful value proposition, which it can design initial product and service offerings to fulfill. This is the stage at which a relatively small band of resources (a founding team armed with an idea, some funding and ambition, and sometimes a technology) is entirely focused on developing a compelling value proposition — fulfilling a significant unmet need, or “job.”9 It’s useful to think of the members of the founding team as completely immersed in this search. The information swirling around them at this point in the journey — the information they pay the most attention to — consists of insights they are able to glean into the unfulfilled jobs of prospective customers.

We emphasize the primacy of the job at this point of the journey because it is very difficult for a business to remain focused on a customer’s job as the operation scales. Understanding the progress a customer is trying to make — and providing the experiences in purchase and use that will fulfill that job perfectly — requires patient, bottom-up inquiry. The language that is characteristic of this stage is the language of questions, not of answers. The link between value proposition and resources is already forming, but the rest of the model is still unformed: The new organization has yet to face the types of recurrent tasks that create processes, and its profit formula is nascent and exploratory. This gives the business an incredible flexibility that will disappear as it evolves along the journey and its language shifts from questions to answers.

Authors Clayton M. Christensen and Derek van Bever discuss how executives can improve their odds of success at business model innovation in this webinar video. Watch now »

Authors Clayton M. Christensen and Derek van Bever discuss how executives can improve their odds of success at business model innovation in this webinar video. Watch now »

2. Sustaining Innovation

Business units lucky and skilled enough to discover an unfulfilled job and develop a product or service that addresses it enter the sustaining innovation phase of the business model journey. At this stage, customer demand reaches the point where the greatest challenge the business faces is no longer determining whether the product fulfills a job, but rather scaling operations to meet growing demand. Whereas in the creation phase the business unit created customers, in the sustaining innovation phase it is building these customers into a reliable, loyal base and building the organization into a well-oiled machine that delivers the product or service flawlessly and repeatedly. The innovations characteristic of this phase of the business model journey are what we call sustaining innovations — in other words, better products that can be sold for higher prices to the current target market.

A curious change sets in at this stage of the journey, however: As the business unit racks up sales, the voice of the customer gets louder, drowning out to some extent the voice of the job. Why does this happen? It’s not that managers intend to lose touch with the job, but while the voice of the job is faint and requires interrogation to hear, the voice of the customer is transmitted into the business with each sale and gets louder with every additional transaction. The voice of the job emerges only in one-to-one, in-depth conversations that reveal the job’s context in a customer’s life, but listening to the voice of the customer allows the business to scale its understanding. Customers can be surveyed and polled to learn their preferences, and those preferences are then channeled into efforts to improve existing products.

The business unit is now no longer in the business of identifying new unmet needs but rather in the business of building processes — locking down the current model. The data that surrounds managers is now about revenues, products, customers, and competition. While in the creation phase, the founding team had to dig to discover data, data now floods the business’s offices, with more arriving with each new transaction. Data begs to be analyzed — it is the way the game is scored — so the influx of data precipitates the adoption of metrics to evaluate the business’s performance and direct future activity to improving the metrics. The performance metrics in this phase focus on the income statement, leading managers to direct investments toward growing the top line and maximizing the bottom line.

3. Efficiency

At some point, however, these investments in product performance no longer generate adequate additional profitability. At this point, the business unit begins to prioritize the activities of efficiency innovation, which reduce cost by eliminating labor or by redesigning products to eliminate components or replace them with cheaper alternatives. (There is, however, always some amount of both types of innovation — sustaining and efficiency — occurring at any point of a business’s evolution.) Broadly, the activities of efficiency innovation include outsourcing, adding financial leverage, optimizing processes, and consolidating industries to gain economies of scale. While many factors can cause businesses to transition into the efficiency innovation phase of their evolution, one we have often observed is the result of performance “overshoot,” in which the business delivers more performance than the market can utilize and consumers become unwilling to pay for additional performance improvement or to upgrade to improved versions. Managers should not bemoan the shift to efficiency innovation. It needs to happen; over time, business units must become more efficient to remain competitive, and the shift to efficiency innovations as the predominant form of innovation activity is a natural outcome of that process.

To managers, the efficiency innovation phase marks the point where the voice of the shareholders drowns out the voice of the customer. Gleaning new understanding of that initial job to be done is now the long-lost ambition of a bygone era, and managers become inundated with data about costs and efficiency. The business unit frequently achieves efficiency by shifting to a modular structure, standardizing the interdependencies between each of the components of its business model so that they may be outsourced to third parties. In hardening these interdependencies, the business unit reaps the efficiency rewards of modularization but leaves flexibility behind, firmly cementing the structure of its business model in place. Deviations from the existing structure undermine the modularity of the components and reduce efficiency, so when evaluating such changes, the business will often choose to forsake them in pursuit of greater efficiency.

Now, when the business unit generates increasing amounts of free cash flow from its efficiency innovations, it is likely to sideline the capital, to diversify the company, or to invest it in industry consolidation. This is one of the major drivers of merger and acquisition (M&A) activity. Whereas the sustaining innovation phase was exciting to managers, customers, and shareholders, the efficiency innovation phase reduces degrees of managerial freedom. Efficiency innovations lure managers with their promises of low risk, high returns, and quick paybacks from cost reduction, but the end result is often a race to the bottom that sees the business’s ability to serve the job and customers atrophy as it improves its service to shareholders.

The natural evolution of business units occurs all around us. Consider the case of The Boeing Co. and its wildly successful 737 business unit. The 737 business was announced in 1965 and launched its first version, the 737-100, in 1967, with Lufthansa as its first customer. With orders from several additional major airlines, the new business unit demonstrated that its medium-haul plane fulfilled an important job to be done. Before even delivering the first -100, Boeing began improving the 737 and launched a stretched version, the -200, with a longer fuselage to meet demands from airlines requiring greater seating capacity. Boeing entered the sustaining innovation phase and continued to improve its product by developing several generations of new 737s, stretching the fuselage like an accordion while nearly doubling the plane’s range and more than doubling its revenue per available seat mile. The business continued to improve how it served customers with the Next Generation series in the 1990s, which offered even bigger aircraft and better avionics systems.

Facing increased competition and demands for improved financial performance, the 737 business shifted its focus to efficiency innovation in the early 2000s. To free resources and liberate capital, Boeing began to outsource aspects of 737 production. Most notably, Boeing sold a facility in Wichita, Kansas, that manufactured the main fuselage platform for the 737 to the Toronto-based investment company Onex Corp. in 2005. Outsourcing subsystem production allowed the business to improve its capital efficiency and deliver improved returns on capital.10

Given that road map, what is the hope for companies that seek to develop new business models or to create new businesses? Thus far in this article we’ve explored the journey that business units take over time. And while we’re not sure that a business unit can break off from this race, we know that its parent companies can — by developing new businesses. Although the processes of an individual business unit’s business model propel it along this journey, the opportunity exists to develop a process of business creation at the corporate level. But doing so successfully requires paying careful attention to the implications of the business model road map.

Implications For Business Model Innovation

It’s worth internalizing the road map view of business model evolution because it helps explain why most attempts to alter the course of existing business units fail. Unaware of the interdependencies and rigidities that constrain business units to pursuing their existing journey, managers attempt to compel existing business units to pursue new priorities or attempt to create a new business inside an existing unit. Using the road map as a guiding principle allows leaders to correctly categorize the innovation opportunities that appear before them in terms of their fit with their existing business model’s priorities. Several recommendations for managers emerge from this insight.

Determine how consistent the opportunity is with the priorities of the existing business model. The only types of innovation you can perform naturally within an existing business model are those that build on and improve the existing model and accelerate its progress along the journey — in other words, those innovations that are consistent with its current priorities — by sharpening its focus on fulfilling the existing job or improving its financial performance. Therefore, a crucial question for leaders to ask when evaluating an innovation opportunity is: To what degree does it align with the existing priorities of the business model?

Many failed business model innovations involve the pursuit of opportunities that appear to be consistent with a unit’s current business model but that in fact are likely to be rejected by the existing business or its customers. (See “Evaluating the Fit Between an Opportunity and an Existing Business.”) To determine how consistent an opportunity is with the priorities of the existing business model, leaders should ask: Is the new job to be done for the customer similar to the existing job? (The greater the similarity, the more appropriate it is for the existing business to pursue the opportunity.) How does pursuit of the opportunity affect the existing profit formula? Are the margins better, transaction sizes larger, and addressable markets bigger? If so, it is likely to fit well with the existing profit formula. If not, managers should tread with caution in asking an existing business to take it on — and should instead consider creating a separate unit to pursue the new business model.

Evaluating the Fit Between an Opportunity and an Existing Business

Determining whether an opportunity aligns to a business’s existing priorities is not an exact science, but there are questions that managers should ask to gauge how closely an opportunity aligns to the existing priorities. The greater the degree of alignment, the better it is to pursue the opportunity through the existing business; conversely, the greater the difference, the more necessary it will be to pursue the opportunity through a separate, dedicated business unit that has the autonomy to develop a unique business model to fulfill those objectives.

In the Creation Stage

In this phase, the entirety of the business unit’s focus should be dedicated to understanding the primary business, accomplished through discovery of the job to be done and “pivoting” of the business model to effectively fulfill the functional, emotional, and social attributes of that job or a superior unfulfilled job that is discovered.

In the Sustaining Innovation Stage

In this phase, managers should evaluate the fit between the opportunity and the existing business unit on the basis of the consistency with the existing unit’s job to be done and the effect on its income statement. Questions managers should ask include:

Does the innovation opportunity …

- Improve our ability to better serve the existing job to be done, in similar circumstances in customers’ lives?

- Grow our current addressable market or bring new customers into our market?

- Improve our revenue growth, profitability, or margins?

- Help us to make more money in the way we are structured to make money?

In the Efficiency Stage

When the business unit is focused on efficiency, managers should evaluate the fit between innovation opportunities and the existing business by the impact on the balance sheet. Questions managers should ask include:

Does the innovation opportunity …

- Enable us to serve our existing customers with lower costs?

- Allow us to use our capital more efficiently?

- Allow us to liberate capital currently invested in the value chain?

- Enable us to modularize our offering to facilitate outsourcing and other partnerships for non-core elements of the model?

This distinction helps explain the performance of the two innovations with which we opened this article. Google saw Google+ as an extension of its search business and chose to integrate Google+ into its existing products and business. Google+ accounts were integrated into other Google products, and the business saw the incorporation of information from users’ social networks as a way to generate improved, tailored search results. Viewed through the lens of Google’s business model, a social network allowed the business to generate greater revenue and profitability by better targeting advertisements and delivering more advertisements through increased usage of its product platform. However, consumers apparently didn’t see the value from combining search and social networking; to the consumer, the jobs are very different and arise in different circumstances in their lives. So while Google maintains its exceptional search business, its social network failed to gain momentum.

Contrast Google’s experience to that of Daimler, which recognized that car2go was a very different business and established it far afield from the home office and existing business. Daimler started car2go as an experiment tested by its employees working in Ulm, Germany. It housed the business in a corporate incubator that does not report to the existing consumer automotive businesses and designed it from the outset to fulfill Daimler’s core job of providing mobility, but without the need to convince consumers to purchase vehicles. Recognizing that the priorities of a business that rents cars by the minute are very different from those involved in selling luxury vehicles, Daimler has kept car2go separate and allowed it to develop a unique business model capable of fulfilling its job profitably. However, car2go benefits from Daimler’s ownership by using corporate resources where appropriate — for example, car2go rents only vehicles in the Daimler portfolio, principally the Smart Fortwo.

To achieve successful business model innovation, focus on creating new business models, rather than changing existing ones. As business model interdependencies arise, the ability to create new businesses within existing business units is lost. The resources and processes that work so perfectly in their original business model do so because they have been honed and optimized for delivering on the priorities of that model. The classic example of this was the movie rental company Blockbuster, which attempted to develop a new DVD-by-mail business in response to the rise of Netflix Inc. by integrating that offering with its existing store network. This “bricks-and-clicks” combination made perfect sense to Blockbuster’s managers, but what became obvious only in hindsight was that the two models would be at war with each other — the asset velocity required to maintain a profitable store network was incompatible with the DVD-by-mail offering. The paradox that managers must confront is that the specialized capabilities that are highly valuable to their current business model will tend to be unsuitable for, or even run counter to, the new business model.

Building a Business Creation Engine

For some time, we’ve argued that companies should build a business creation engine, capable of turning out a steady stream of innovative new business models, but to date no company we know of has built an enduring capability like that. We think that such an engine of sustained growth would quickly prove to be a company’s most valuable asset, providing growth and creating new markets. But unleashing this growth potential requires very different behaviors than those required to successfully exploit existing markets.

The challenge, as the journey metaphor we’ve developed here should make clear, is that what is necessary is to turn an event — the act of creating a new business and a new business model — into a repeatable process at the corporate level. It must be a process because events are discrete activities with definitive start and end points, whereas processes are continuous and dynamic. Learnings from a previous event do not naturally or easily flow to subsequent events, causing the same mistakes to be repeated over and over. In contrast, processes by their nature can be learning opportunities that incorporate in future attempts what was discovered in previous iterations. Enacted as a process, the act of creation will improve over time and refine its ability to discover unfulfilled customer jobs and create new markets; the success rate will improve alongside the process, creating a virtuous cycle of growth.

While we have not discovered a perfect exemplar of this discipline, we have been tracking the efforts of some leading companies that are intent on building such a capability. While it is too early to hold any of them up as success stories, we can nonetheless discern five approaches that we believe have the potential to lead to success. Let’s look at each of these approaches in turn.

Spot future growth gaps by understanding where each of your business units is on the journey. In our course at Harvard Business School, we teach students to use a tool called the aggregate project plan to allocate funding to different types of innovation.11 Such a plan categorizes innovations by their distance from existing products and markets and specifies a desired allocation of funding to each bucket. We see application for this tool here as well.

The innovation team at Carolinas HealthCare System, a not-for-profit health care organization based in Charlotte, North Carolina, performed this type of analysis and identified a need to field additional innovation efforts that reflected the organization’s belief that hospitals will be less central in the health care system of the future. Armed with this view, Carolinas HealthCare System has been able to plan innovation activity by type, ensuring that the organization invests appropriately across all three categories of the business model journey. As Dr. Jean Wright, chief innovation officer at Carolinas HealthCare System, said, “The strength of the journey framework is that it allowed us to see that our investments in business creation are very different from our investments in our existing businesses. More importantly, it has helped us see that both types are important.”

Run with potential disruptors of your business. Another approach is to create incentives and channels for entrepreneurs to bring new and, in some cases, potentially disruptive business models to you, either as potential customers or as ecosystem partners. ARM Holdings plc, a developer and licenser of system-on-chip semiconductors, headquartered in Cambridge, U.K., has had success viewing itself as the central, coordinating node of a symbiotic ecosystem of independent semiconductor manufacturers and consumer products companies, rather than as a traditional semiconductor company that develops and manufactures proprietary, standard products. Today, nearly every smartphone and mobile device includes at least one ARM design. The company achieved this ubiquity by inviting customers and consumers into its development process so that it will be the first company called by customers seeking to design a new chip. It does this in two ways: first, by incorporating knowledge across its entire ecosystem that allows it to develop optimized end-to-end solutions for customers, and second, by employing a royalty-based revenue model that ensures ARM’s incentives are aligned with those of its customers.

Start new businesses by exploring the job to be done. When identifying new market opportunities, it’s critical that you begin with a focus on the customer’s job to be done, rather than on your company’s capabilities. It’s tempting to look at your capabilities as the starting point for any expansion, but capabilities are of no use without a job for them. For incumbents, this requires staying focused on the job rather than the market or capability. One example of this discipline is Corning Inc., the manufacturer of specialty glass and ceramic materials based in Corning, New York. When it becomes apparent that a Corning business can no longer generate a premium price from its technical superiority — when it reaches the efficiency innovation stage, in our framework — the company divests that business and uses the proceeds to expand businesses in the sustaining stage and to create new ones. For example, when Corning realized that liquid crystal display (LCD) would eventually replace cathode ray tube (CRT) technology to become the future of display, the company focused on the job to be done — display — rather than just on the CRT market, which at the time was important to the company. Corning began inventing products to enable the growth of the LCD industry and eventually decided to exit the CRT market.12 To Corning, businesses serve needs, not markets, and as technological or market shifts occur, the company continues to grow by remaining focused on the need, which we call the job.

Resist the urge to force new businesses to find homes in existing units. When executives start new businesses, they often look at them and wonder, “Where do I stick this in my organization?” They feel pressure to combine new businesses with existing structures to maximize efficiency and spread overhead costs over the widest base, but this can spell doom for the new business. When a new business is housed within an existing unit, it must adopt the priorities of the existing business to secure funding; in doing so, the new business often survives in name but disappears in effect.

Once a new business is launched, it must remain independent throughout the duration of its journey, but maintaining autonomy requires ongoing leadership attention. The forces of efficiency operate 24/7 inside an organization, rooting out any cost perceived to be superfluous; standing against these forces requires the constant application of a counterforce that only the company’s most senior leaders can provide. In the quest for efficiency, what has been somehow forgotten is the vital leadership role that corporate executives can play in fostering organizational innovation by countenancing the creation of multiple profit formulas and housing these different businesses in a portfolio of business models.

Use M&A to create internal business model disruption and renewal. Lastly, while we’ve focused most of our attention on organic activities, there’s a very valuable role for M&A in a business growth engine.13 Although at the extreme, this approach can result in a quasi-conglomerate structure that history has proved to be ineffective, there are exceptions. EMC Corp., based in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, adopted this approach with the creation of its federation structure when it floated VMware Inc., a company it had acquired three years earlier, as a publicly traded subsidiary in 2007. Much M&A activity designed to change an existing business model fails because it’s done for the wrong reasons and managed in the wrong way, often resulting in the integration of units that should remain autonomous. In contrast, EMC’s federation structure allows each business to pursue its individual objectives while coordinating the company’s activity as a whole. This embedded capability for exploiting existing markets while identifying and investing in new markets allowed EMC to expand out of its traditional memory business into machine virtualization, agile development, and information security.

The Greatest Innovation Risk

Executives sometimes prefer to invest in their existing businesses because those investments seem less risky than trying to create entirely new businesses. But our understanding of the business model journey allows us to see that, over the long term, the greatest innovation risk a company can take is to decide not to create new businesses that decouple the company’s future from that of its current business units.

We take great hope from the insights about business model innovation and corporate renewal that we have explored in this article — not because we believe that business units can evade or escape the journey that we have described, but because we believe that the corporations that house these units can. There remains much to be learned about corporate renewal and the business model journey, but we hope that insights from the business model road map can help companies learn how to create robust corporate-level business creation engines that will renew their organizations and power growth. The challenge is great — but so are the potential rewards.

About the Authors

Clayton M. Christensen is the Kim B. Clark Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School in Boston, Massachusetts. Thomas Bartman is a former senior researcher at the Forum for Growth and Innovation at Harvard Business School. Derek van Bever is a senior lecturer of business administration at Harvard Business School, as well as director of the Forum for Growth and Innovation.

References

1. PwC, “2015 US CEO Survey: Top Findings — Grow and Create Competitive Advantage,” n.d., www.pwc.com.

2. Z. Lindgardt and M. Ayers, “Driving Growth with Business Model Innovation,” October 8, 2014, www.bcg.perspectives.com.

3. See D.A. Garvin, “The Processes of Organization and Management,” Sloan Management Review 39, no. 4 (summer 1998): 33-50. In discussing processes, we refer to all of the processes that Garvin identified in that article.

4. This business model framework was developed in 2008; see M.W. Johnson, C.M. Christensen, and H. Kagermann, “Reinventing Your Business Model,” Harvard Business Review 86, no. 12 (December 2008): 50-59.

5. For more information about organizational capabilities, see C.M. Christensen and S.P. Kaufman, “Assessing Your Organization’s Capabilities: Resources, Processes, and Priorities,” module note 9-607-014, Harvard Business School, Boston, Massachusetts, August 21, 2008, http://hbr.org.

6. See E.H. Schein, “Organizational Culture and Leadership” (San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass, 1985).

7. It’s worth noting that startups typically begin with one business unit, which is the company. Then as the organization grows, companies typically create corporate offices and business units that separate responsibility for the administration of the organization from the specific business. Today, managers tend to operate lean corporate offices that often function as thin veneers between the business and investors, but we believe that there is a vital role for the corporate office in leading business creation and developing innovation.

8. P.F. Drucker, “The Practice of Management” (New York: Harper & Row, 1954).

9. For a more complete treatment of jobs to be done, see C.M. Christensen, T. Hall, K. Dillon, and D.S. Duncan, “Competing Against Luck: The Story of Innovation and Customer Choice” (New York: HarperCollins, in press).

10. W. Shih and M. Pierson, “Boeing 737 Industrial Footprint: The Wichita Decision,” Harvard Business School case no. 612-036 (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2011, revised 2012).

11. S.C. Wheelwright and K.B. Clark, “Creating Project Plans to Focus Product Development,” Harvard Business Review 70, no. 2 (March-April 1992): 70-82.

12. Authors’ teleconference with David L. Morse, executive vice president and chief technology officer, Corning Inc., March 8, 2016.

13. J. Gans, “The Disruption Dilemma” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2016).

Reprint #:

58123

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)