Managing Organizational Change

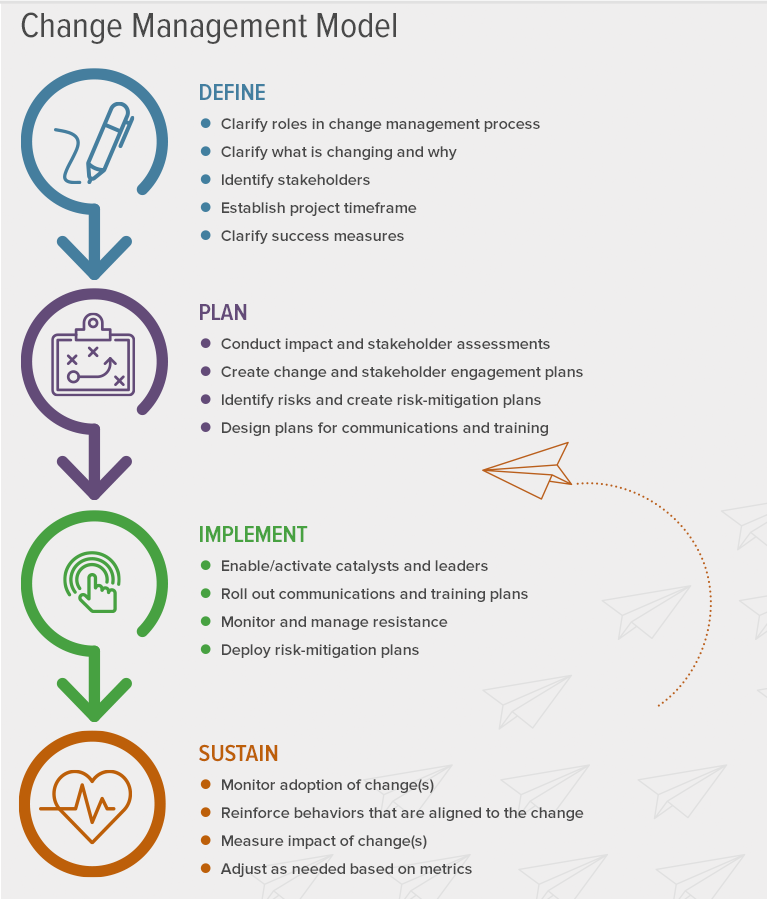

Another model for organizational change includes a four-phase change management process:

A large global retailer uses this model to increase the speed and impact of change initiatives while reducing the downturn of performance, thereby achieving desired outcomes quicker.

There are numerous change models available for employers to consider. For a general overview of different models, see the Confident Change Management website.

Overcoming Common Obstacles Encountered in Implementing Change

Organizations can have a clear vision for changes and a technically and structurally sound foundation for making changes, but the initiatives can still flounder due to obstacles that arise. Employee resistance and communication breakdown are common obstacles faced during major organizational change.

See How to Avoid Common Mistakes in Change Management.

Employee resistance

Successful change starts with individuals, and failure often occurs because of human nature and reluctance to change. Employees may also lack the specific behavioral traits needed to adapt easily to changing circumstances, which could decrease employee engagement and effectiveness and put organizational productivity at risk. How organizations treat workers during a change initiative determines how successful the change—and the organization—will be.

There are six states of change readiness: indifference, rejection, doubt, neutrality, experimentation and commitment. Organizations about to embark on a transformation should evaluate workforce readiness with assessment instruments and leader self-evaluations to identify the areas in which the most work is needed.

Leaders should have a solid strategy for dealing with change resistance. Some actions to build employee change readiness include:

- Developing and cascading strong senior sponsorship for people-focused work. In the absence of visible sponsorship, leaders should build alliances, meet business needs and promote wins.

- Developing tools and information for front-line supervisors and managers. Organizations should involve them early—train them, prepare them and communicate regularly.

- Coaching employees to help them adapt and thrive during change.

- Rewarding desired behaviors and outcomes with both tangible and intangible rewards.

- Relying on insights from both those in the field and subject-matter experts.

Communication breakdown

Sometimes decisions about major organizational changes are made at the top management level and then trickle down to employees. As a result, why and how the company is changing may be unclear. According to a Robert Half Management Resources survey, poor communication commonly hinders organizational change-management efforts, with 65 percent of managers surveyed indicating that clear and frequent communication is the most important aspect when leading through change.

To avoid this problem, HR should be involved in change planning early to help motivate employees to participate. Effective communication promotes awareness and understanding of why the changes are necessary. Employers should communicate change-related information to employees in multiple forms (e.g., e-mails, meetings, training sessions and press releases) and from multiple sources (e.g., executive management, HR and other departments).

See Why United Airlines’ Lottery-Based Bonus Idea Fell Flat.

To avoid communication breakdowns, change leaders and HR professionals should be aware of five change communication methodologies—from those that provide the greatest amount of information to those that provide the least:

- “Spray and pray.” Managers shower employees with information, hoping they can sort significant from insignificant. The theory is that more information equates to better communication and decision-making.

- “Tell and sell.” Managers communicate a more limited set of messages, starting with key issues, and then sell employees on the wisdom of their approach. Employees are passive receivers, and feedback is not necessary.

- “Underscore and explore.” Managers develop a few core messages clearly linked to organizational success, and employees explore implications in a disciplined way. Managers listen for potential misunderstandings and obstacles. This strategy is generally the most effective.

- “Identify and reply.” Executives identify and reply to key employee concerns. This strategy emphasizes listening to employees; they set the agenda, while executives respond to rumors and innuendoes.

- “Withhold and uphold.” Executives withhold information until necessary; when confronted by rumors, they uphold the party line. Secrecy and control are implicit. The assumption is that employees are not sophisticated enough to grasp the big picture.

Experts estimate that effective communication strategies can double employees’ acceptance of change. However, often companies focus solely on tactics such as channels, messages and timing while failing to do a contextual analysis and consider the audience. Some of the specific communication pitfalls and possible remedies for them are the following:

- The wrong messengers are used. Studies have found that employees tend to trust information from managers. Understanding the organization’s culture will dictate who is the best messenger for change—the manager, the senior executive team or HR.

- The change is too sudden. Leaders and managers need to prepare employees for change, allow time for the message to sink in and give them an opportunity to provide feedback before a change is initiated.

- Communication is not aligned with business realities. Messages should be honest and include the reasons behind the change and the projected outcomes.

- Communication is too narrow. If the communication focuses too much on detail and technicalities and does not link change to the organization’s goals, it will not resonate with employees.

Executive leaders and HR professionals must be great communicators during change. They should roll out a clear, universal, consistent message to everyone in the organization at the same time, even across multiple sites and locations. Managers should then meet both with their teams and one on one with each team member.

Leaders should explain the change and why it is needed, be truthful about its benefits and challenges, listen and respond to employees’ reactions and implications, and then ask for and work to achieve individuals’ commitment.

See Keep it Clear: Three Ways to Help Communicate Change in Your Organization and

Managing Organizational Communication.

Other obstacles

Employee resistance and communication breakdowns are not the only barriers that stand in the way of successful change efforts. Other common obstacles include:

- Insufficient time devoted to training about the change.

- Staff turnover during the transition.

- Excessive change costs.

- An unrealistic change implementation timeline.

- Insufficient employee participation in voluntary training.

- Software/hardware malfunctions.

- Downturn in the market or the economy.

Change management experts have suggested that unsuccessful change initiatives are often characterized by the following:

- Being too top-down. Executives relate their vision of what the end result of the change initiative should be, but do not give direction or communication on how the managers should make the change happen.

- Being too “big picture.” The organization’s leaders have a vision of the change but no idea of how that change will affect the individuals who work there.

- Being too linear. Managers work the project plan from start to finish without making even necessary adjustments.

- Being too insular. Most organizations do not seek outside help with change initiatives, but businesses may need objective external input or assistance to accomplish major changes.

Successful change management must be well-planned, well-timed and well-integrated. Other critical success factors include a structured, proactive approach that encompasses communication, a road map for the sponsors of the change, training programs that go along with the overall project and a plan for dealing with resistance. Change leaders need to be active and visible in sponsoring the change, not only at the beginning but also throughout the process. Turning their attention to something else can send employees the wrong message—that leaders are no longer interested.

Managing Varied Types of Major Organizational Change

Organizational change comes in many forms. It may focus on creating new systems and procedures; introducing new technologies; or adding, eliminating or rebranding products and services. Other transformations stem from the appointment of a new leader or major staffing changes. Still other changes, such as downsizing or layoffs, bankruptcy, mergers and acquisitions, or closing a business operation, affect business units or the entire organization. Some changes are internal to the HR function.

In addition to the general framework for managing change, change leaders and HR professionals should also be aware of considerations relating to the particular type of change being made. The subsections below highlight some of the special issues and HR challenges.

Mergers and acquisitions

A merger is generally defined as the joining of two or more organizations under one common ownership and management structure. An acquisition is the process of one corporate entity acquiring control of another by purchase, stock swap or some other method. Nearly two-thirds of all mergers and acquisitions (M&As) fail to achieve their anticipated strategic and financial objectives. This rate of failure is often attributed to HR-related factors, such as incompatible cultures, management styles, poor motivation, loss of key talent, lack of communication, diminished trust and uncertainty of long-term goals.

HR professionals face several challenges during M&As, including the following:

- Attempting to maintain an internal status quo or to effect change—either to facilitate or thwart (in the case of a hostile takeover) a possible merger or acquisition, as instructed by upper management.

- Communicating with employees at every step in the M&A process with appropriate levels of disclosure and secrecy.

- Devising ways to meld the two organizations most effectively, efficiently and humanely for the various stakeholders.

- Dealing with the reality that M&As usually result in layoffs of superfluous employees. This process entails coordinating separation and severance pay issues between the combining organizations.

- Addressing the ethical dilemmas involved, such as when an HR professional may be required to eliminate his or her own position or that of a co-worker or an HR counterpart in the combined organization.

Downsizing

Successfully implementing a layoff or reduction in force (RIF) is one of the more difficult change initiatives an HR professional may face. Tasks HR professionals will need to undertake include:

- Planning thoroughly. Each step in the process requires careful planning, considering alternatives, selecting employees to be laid off, communicating the layoff decision, handling layoff documentation and dealing with post-layoff considerations.

- Applying diversity concepts. HR should form a diverse team to define layoff criteria and make layoff selections.

- Addressing the needs of the laid-off. This step involves reviewing severance policies, outplacement benefits, unemployment eligibility and reference policies.

- Dealing with the emotional impact. HR professionals should understand and prepare for the emotional impact of layoffs on the downsized employees and their families, on the managers making layoff decisions, on other HR professionals involved, and on remaining employees and managers working with the post-layoff workforce. In some situations, an HR professional may even be responsible for implementing his or her own layoff, a case calling for the utmost in professional behavior.

- Managing the post-layoff workforce.

See Managing Downsizing by Means of Layoffs and

Drive Team Performance Using Organizational Transformation.

Bankruptcy

Filing for a business bankruptcy and successfully emerging from the process is generally a complex and difficult time for all parties. HR may have to cut staff, reduce benefits, change work rules or employ a combination of such actions. A major strategic concern during a Chapter 11 bankruptcy is retaining key personnel.

Compassion, frequent communication and expeditious decision-making will help reduce the stress an organization’s employees are likely to experience during this difficult organizational change. Showing genuine respect for people and treating them with honesty, dignity and fairness—even as difficult decisions are being made about pay, benefits and job reductions—will drive the success or failure of an organization post-bankruptcy.

See Managing Human Resources for a Company in Bankruptcy.

Closing a business operation

Businesses make the difficult decision to close all or part of their operations for many reasons, including economic recession, market decline, bankruptcy, sale, a realignment of operations, downsizing, reorganization, outsourcing or loss of contracts.

HR professionals will play an integral role during such business closures, from developing the plan for the closure through the final stages of shutdown. Some of HR’s major responsibilities during this type of organizational change are listed below:

- Following facility-closing notification laws. HR must determine whether and to what extent the business must comply with notification requirements under federal or state laws for mass layoff and facility closings. HR will also lead the announcement process and participate in all aspects of employee communications, which may include all-employee meetings, written announcements and media interviews.

- Announcing the closure news. HR has an important role to play in anticipating and responding to workforce reactions by having as much information and resources on hand as possible. To avoid hostilities or other destructive behavior, HR should consider using an employee assistance program or an outplacement firm.

- Providing employee benefits information. After the shock of the announcement subsides, the most frequently asked questions involve benefits, including unemployment compensation, health care continuation, pension plan issues, and retirement plan distributions and rollovers.

- Coordinating outplacement services. Offering outplacement services for departing employees may enable business owners and managers to provide much-needed support and protect the organization’s reputation. If financially feasible, the organization may offer departing employees outplacement services from a private outplacement consulting firm or, in some states, a state agency.

- Negotiating with unions. In unionized facilities, employers have a duty to bargain about the effects of a business closure decision. These negotiations typically involve assistance benefits, seniority issues, pension plan issues and employment opportunities at facilities not affected by the closure.

- Costing the closure. Anticipating the costs of a business closure is critical from an early stage of the process and will fall heavily on HR. This procedure involves assessing the cost of winding down employee benefits, assistance benefits, payroll and administrative costs, severance payments, union demands, unresolved employee claims or charges, security precautions, and any closing notification penalties.

- Disposing of company property. HR should know the organization’s policy for disposal of company property and respond to employees’ requests for office furniture, equipment, machinery and other tangible business assets. If the business does not sell or transfer assets or is not in debt to creditors, HR may help determine whether to give items to employees, community groups, schools or other potential recipients.

- Complying with legal requirements. Numerous legal issues surround the closing of a business. Depending on the number of employees and the employer’s commitments to employee benefits programs, legal compliance may require following closing-notification requirements, sending out COBRA notices and termination letters, issuing final paychecks, making any required severance payments and communicating unemployment compensation. HR must know how to comply with the laws and avoid litigation risks.

Outsourcing

For several reasons, including cost savings and freeing staff to focus on more strategic efforts, an organization may decide to outsource HR or other business functions. Outsourcing is a contractual agreement between an employer and a third-party provider whereby the employer transfers the management of and responsibility for certain organizational functions to the external provider. Many types of outsourcing options are available to employers, from outsourcing one aspect of a single function to outsourcing an entire functional department. This change can have a similar impact on employees as downsizing or closing a department.

When deciding whether to outsource, an organization should carefully consider questions about its needs in a particular functional area, current processes, business plan and outsourcing options, including:

- Does the situation merit outsourcing?

- Is the department providing excellent service with existing staff and processes? Is it meeting the organization’s needs?

- Can the affected department handle outsourcing without disrupting operations?

- Will the CEO and top management team support and pay for an outside vendor?

- How might an outsourcing arrangement fall short of expectations? How can such risks be mitigated?

During an HR outsourcing process, HR professionals may be asked to identify solutions to guide organizations through vendor selection and management of the outsourcing relationship.

See Outsourcing the HR Function.

Changes within HR

HR professionals frequently help other parts of the organization respond to change, but what happens when the HR department becomes the epicenter of change? These kinds of transformations, such as moving to a shared services model, integrating with another HR function following a merger or delivering new services to new clients, can be more difficult for HR professionals to manage than other types of organizational changes.

During major changes within the HR function, HR should do the following:

- Lead by example. Do exactly what HR asks other leaders and managers to do during major change initiatives.

- Remember that HR professionals’ responsibilities never cease. The HR department must continue to serve employees while contending with the discomfort, confusion and demands that department-specific change creates.

- Keep in mind that few organizational changes occur in isolation. If senior leaders decide to implement an HR shared services model, for instance, the information technology, finance and procurement functions also could move to a similar model or initiating efficiency projects.

- Measure the degree to which HR staff is prepared to change before plunging into the change. HR leaders should assess staff readiness and engagement through interviews and surveys. After evaluating the results, they should make necessary adjustments in staff readiness and engagement levels before proceeding.

- Realize that most HR transformations require fresh, or refreshed, talent. HR leaders can fire and hire, or they can retrain and develop.

Legal Issues

In addition to managing the “people side” of organizational change initiatives, HR professionals should keep leadership informed of any applicable employment laws and the potential legal implications of various types of change. Typically, HR will be responsible, in consultation with legal counsel, for ensuring compliance with pertinent federal, state, local and international employment laws and regulations.

Legal compliance requirements may vary considerably based on the nature of the change initiative, the location(s) and size of the organization, whether the employer is unionized, and other factors. Federal laws that may apply to particular organizational change initiatives include:

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

- Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA).

- Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

- National Labor Relations Act (NLRA).

- Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act (WARN) of 1988.

- Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996.

- Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA).

See Federal Statutes, Regulations and Guidance.

HR professionals may also be responsible for negotiating contracts with unions, service providers or vendors. In such cases, they need to be familiar with key contract terms and issues and be able to represent the organization’s interests effectively in contract negotiations and management.

Global Issues

Significant organizational changes can create ongoing conflict between two locations in the same country. But conflict is more likely to occur, and is harder to address, when differences in language, time zones, institutions and business practices exist. According to research conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit, companies will continue to become larger and more global, handling operations in more countries than they do today.4

Culturally based assumptions about customer needs, infrastructure, competitive threats and other factors make it more difficult to find common ground during a cross-cultural change initiative. What differentiates an organization’s products or services in one country may not be the same elsewhere, and the strengths that it has in its home market may not be easily replicated in other countries.

Common problems in cross-cultural change initiatives include:

- Lack of a partnership approach. It is natural for an organization to consider its home market and its largest customers when planning change efforts. However, those voices can easily drown out the needs of employees or clients in distant markets, including those that could have high growth potential. By partnering with all employees and clients from the beginning and considering future potential for revenue, profit and growth, an organization can build an approach to change that integrates the patterns of past successes with future directions.

- Misreading similarities and differences in markets. Multinational organizations might project solutions suitable for one country onto another country or assume that customers abroad want to behave “more like us.” To make matters more complicated, foreign products may have considerable appeal in some markets but often for reasons that only make sense in the local context. Companies may expect the same competitive landscape, yet the largest competitive threats may come from companies that are unknown back at headquarters.

- Not enough accountability. Establishing accountability at the local level is difficult when employees lack a sense of ownership for a new initiative. This situation can be exacerbated by the typical matrix organizational structure at many global companies. Employees who report into both a global business unit and a local management structure frequently pay the closest attention to the managers they encounter every day who are most likely to affect their futures.

Leaders of global change initiatives should consider these potential problems and plan to address them in advance. They will be far more likely to avoid change-related pitfalls; achieve their objectives; and build business partnerships characterized by mutual learning and superior business results.

Available in the SHRM Store: Agile Change Management: A Practical Framework for Successful Change.

Endnotes

1Gartner. (2018). Change Management. Retrieved from

https://www.gartner.com/en/insights/change-management

2Willis Towers Watson. (2013, August 29). Only one-quarter of employers are sustaining gains from change management initiatives, Towers Watson survey finds. Retrieved from

https://www.towerswatson.com/en/Press/2013/08/Only-One-Quarter-of-Employers-Are-Sustaining-Gains-From-Change-Management

3Kotter, John. (2014). Accelerate: Building strategic agility for a faster-moving world. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

4Economist Intelligence Unit. (2010). Global firms in 2020: The next decade of change for organisations and workers. Retrieved from

https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/Documents/10-Economist%20Research%20-%20Global%20Firms%20in%202020.pdf

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)