Here’s one way to make solar energy more affordable and accessible: Share it with your neighbors

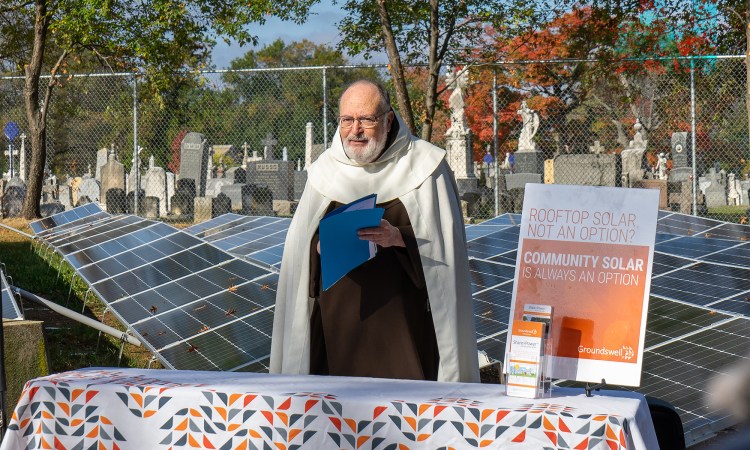

Photos courtesy of Groundswell

Climate change is driving social inequities across the globe. People from low-income communities are at higher risk of heat-related illness, and they’re less likely to have access to clean water and more likely to be exposed to toxic air pollution.

It’s clear that protecting vulnerable communities from the perils of climate change also means that we need to reimagine our energy systems and transition from carbon-polluting fossil fuels to clean, renewable energy. But it turns out, not everyone has the same access to energy, including the same communities that are being hardest hit by climate change. So how do we provide a growing population with green and affordable energy while protecting the planet?

“Our energy systems need a fundamental, values-based transformation because our current energy systems are rooted in and reinforce structural racism through how power is generated, distributed and controlled,” explains Michelle Moore, the CEO of Groundswell, a Washington DC-based nonprofit that builds community solar projects and a grantee of the Solutions Project, a nonprofit that supports climate innovators at the grassroots.

Here’s why our current energy system is inequitable — and how we can change it while combating the climate crisis.

How the energy system reinforces centuries of racism

Economic and housing disparities are deeply embedded in the US. Prior to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, Black people were systematically denied mortgages and loans that made owning a home accessible, a practice known as redlining. This, along with other racist housing policies, meant Black Americans were often forced into low-income neighborhoods with limited access to economic and educational opportunities — and the consequences of these policies continue.

The more money that people need to spend on utilities, the less they have to spend on all their other basic necessities, including housing, food, healthcare and education.

Today Black Americans are more likely to live in older housing with poor ventilation, inefficient appliances and outdated heating and cooling systems. Households in residentially segregated neighborhoods are also more likely to experience energy insecurity, meaning they’re unable to afford basic energy needs. Low-income households also tend to have a higher household “energy burden,” meaning a higher percentage of their total income goes to energy bills.

On average, low-income households spend 8.1 percent of their income on utilities, while higher-income households spend only 2.3 percent. In seven US states, low- and moderate-income household energy burdens exceed a staggering 20 percent, including Alabama (20.9 percent), Mississippi (26.7 percent) and South Carolina (22 percent). And the more money that people need to spend on utilities, the less they have to spend on all their other basic necessities, including housing, food, healthcare and education. Plus, research suggests that difficulty paying energy bills is associated with chronic stress, which is in turn related to poor mental and physical health outcomes.

But America’s unequal energy system poses a much more direct health hazard too. As global temperatures rise, the World Health Organization predicts that by 2050 255,000 people will die annually from heatwaves. In the US, this extreme heat threatens Black households in urban areas who are less likely to have access to air conditioning, as compared to white households.

What is community solar?

Homes in the US are responsible for around one-fifth of the country’s energy-related carbon emissions. Making renewable energy, like solar, more accessible to everyone can help us simultaneously reduce carbon pollution and help address racial and economic inequity.

Scaling up shared solar and making low-income housing as energy-efficient as the average US home could eliminate people’s energy burden by 35%.

However, there are several challenges in making solar energy widely available to people. For example, the cost of installing solar panels on an average US home is about $20,000. Although that upfront cost has decreased in the past two decades and generates long-term economic savings, it’s still not financially accessible for many homeowners and virtually impossible for renters.

There are also structural limitations. People may not have sufficient rooftop space on their homes or get enough sun exposure, and roofs on older structures may not be able to support the panels.

So what can we do to bring affordable, green energy to the people who need it?

“Community solar works by sharing power with residents from a centralized solar array,” Moore explains. These solar arrays can range in size from a single rooftop to a small solar farm in a field. “For example, a Groundswell solar array installed at the Monastery of Our Lady of Mt. Carmel in the District of Columbia provides solar power for more than 50 local families.”

Community solar projects like this one are owned by a third party that allows participants to purchase a subscription and receive a share of the solar-generated electricity, removing the hurdle of installing solar panels on individual homes. “It’s accessible whether you own or rent your home, and it enables communities to come together to share power,” Moore says. “[It] can be a beautiful way for communities to own their own power.”

These projects can yield big energy savings for those most in need. For example, Groundswell’s “SharePower” community solar model is designed to prioritize households with the highest energy burdens. “We’re currently serving more than 4,000 families more than $2 million per year in solar savings,” Moore says, or around $500 per year in utility bill savings for each household.

Scaling up shared solar and making low-income housing as energy-efficient as the average US home could reduce people’s energy burden by 35 percent — and the potential savings are even higher for Black (42 percent) and Latinx (68 percent) households.

Reducing energy-related carbon pollution benefits everyone regardless of income — it reduces emissions, creates green jobs and increases air quality.

But to date, only 20 states have enacted community solar laws, which is legislation that allows more than one person or organization to own a photovoltaic array. “If your state doesn’t have a community solar law, you can’t create your community solar project to share power with your neighbors,” Moore explains.

So, if you live in the US, one of the biggest things you can do to improve energy access and affordability is to ask local policymakers to pass legislation that allows communities to operate on locally-owned solar power or join a relevant organization. In Pennsylvania, for example, a bipartisan coalition of solar advocates, from farmers to lawmakers, is pushing for a new bill to allow community solar in the state. Reducing energy-related carbon pollution benefits everyone regardless of their income bracket: It reduces greenhouse gas emissions, creates green jobs and increases air quality.

“Unless we take steps to reform our energy systems, the solar market is on a track to replicate the racial, gender and economic disparities of the fossil fuel industry,” Moore says. Change starts with using your voice.

Stretching over roughly 9 million square kilometers, the Sahara Desert receives about 22 million terawatt hours of energy from the Sun each year. Watch this TED-Ed lesson to find out whether we should tap into it:

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)