9 Strategic Planning Models and Tools for the Customer-Focused Business

What’s a plan without a strategy?

As the economist and business strategy guru, Michael Porter, says, “The essence of strategy is choosing what not to do.”

With strategic planning, businesses identify their strengths and weaknesses, choose what not to do, and determine which opportunities should be pursued. In sales operations, having a clearly defined strategy will help your organization plan for the future, set viable goals, and achieve them.

So, how do you get started with strategic planning? You’ll begin with strategic planning models and tools. Let’s take a look at nine of the most prominent ones here.

Strategic Planning Models

Strategic planning is used to set up long-term goals and priorities for an organization. A strategic plan is a written document that outlines these goals.

Don’t confuse strategic planning and tactical planning. Strategic planning is focused on long-term goals, while tactical planning is focused on the short-term.

Free Resource

Free Strategic Planning Template

Fill out the form to access your business strategic planning template.

Here are a few strategic planning models you can use to get started.

1. The Balanced Scorecard

The Balanced Scorecard is one of the most prominent strategic planning models, tailored to give managers a comprehensive overview of their companies’ operations on tight timelines. It considers both financial and operational metrics to provide valuable context about how a business has performed previously, is currently performing, and is likely to perform in the future.

The model plays on four concerns: time, quality, performance and service, and cost. The sum of those components amount to four specific reference points for goal-setting and performance measurement:

- Customer — how customers view your business

- Internal Process — how you can improve your internal processes

- Organizational Capacity — how you can grow, adapt, and improve

- Financial — your potential profitability

Those four categories can inform more thoughtful, focused goals and the most appropriate metrics you can use to track them. But the elements you choose to pursue and measure are ultimately up to you. They will vary from organization to organization — there’s no definitive list.

That being said, there’s a universally applicable technique you can use when leveraging the model — creating a literal scorecard. It’s a document that keeps track of your goals and how you apply them. Here’s an example of what that might look like:

Image Source: IntraFocus

The Balanced Scorecard is ideal for businesses looking to break up higher-level goals into more specific, measurable objectives. If you’re interested in translating your big-picture ambitions into actionable projects, consider looking into it.

Example of the Balanced Scorecard

Let’s imagine a B2B SaaS company that sells a construction management solution. It’s been running into trouble from virtually all angles. It’s struggling with customer retention and, in turn, is hemorrhaging revenue. The company’s sales reps are working with very few qualified leads and the organization’s tech stack is limiting growth and innovation.

The business decides to leverage a Balanced Scorecard approach to remedy its various issues. In this case, the full strategic plan — developed according to this model — might look like this:

- The company sets a broad financial goal of boosting revenue by 10% year over year.

- To help get there, it aims to improve its customer retention rate by 5% annually by investing in a more robust customer service infrastructure.

- Internally, leadership looks to improve the company’s lead generation figures by 20% year over year by revamping its onboarding process for its presales team.

- Finally, the business decides to move on from its legacy tech stack in favor of a virtualized operating system — making for at least 50% faster software delivery for consistent improvements to its product.

The elements listed above address key flaws in the company’s customer perception, internal processes, financial situation, and organizational capacity. Every improvement the business is hoping to make involves a concrete goal with clearly outlined metrics and definitive figures to gauge each one’s success. Taken together, the organization’s plan abides by the Balanced Scorecard model.

2. Objectives and Key Results

As its name implies, this model revolves around translating broader organizational goals into objectives and tracking their key results. The framework rests on identifying three to five attainable objectives and three to five results that should stem from each of them. Once you have those in place, you plan initiatives around those results.

After you’ve figured out those reference points, you determine the most appropriate metrics for measuring their success. And once you’ve carried out the projects informed by those ideal results, you gauge their success by giving a score on a scale from 0 to 1 or 0%-100%.

For instance, your goal might be developing relationships with 100 new targets or named accounts in a specific region. If you only were able to develop 95, you would have a score of .95 or 95%. Here’s an example of what an OKR model might look like:

Image Source: Perdoo

It’s recommended that you structure your targets to land at a score of around 70% — taking some strain off workers while offering them a definitive ideal outcome. The OKR model is relatively straightforward and near-universally applicable. If your business is interested in a way to work towards firmly established, readily visible standards this model could work for you.

Example of the Objectives and Key Results

Let’s consider a hypothetical company that makes educational curriculum and schedule planning for higher-education institutions. The company decides it would like to expand its presence in the community college system in California — something that constitutes an objective.

But what will it take to accomplish that? And how will the company know if it’s successful? Well, in this instance, leadership at the business would get there by establishing three to five results they would like to see. Those could be:

- Generating qualified leads from 30 institutions

- Conducting demos at 10 colleges

- Closing deals at 5 campuses

Those results would lead to initiatives like setting standards for lead qualification and training reps at the top of the funnel on how to use them appropriately, revamping sales messaging for discovery calls, and conducting research to better tailor the demo process to the needs of community colleges.

Leveraging this model generally entails repeating that process between two and four more times — ultimately leading to a sizable crop of thorough, actionable, ambitious, measurable, realistic plans.

3. Theory of Change (TOC)

The Theory of Change (TOC) model revolves around organizations establishing long-term goals and essentially “working backward” to accomplish them. When leveraging the strategy, you start by setting a larger, big-picture goal.

Then, you identify the intermediate-term adjustments and plans you need to make to achieve your desired outcome. Finally, you work down a level and plan the various short-term changes you need to make to realize the intermediate ones. More specifically, you need to take these strides:

- Identify your long-term goals.

- Backward map the preconditions necessary to achieve your goal, and explain why they’re necessary.

- Identify your basic assumptions about the situation.

- Determine the interventions your initiative will fulfill to achieve your goals.

- Come up with indicators to evaluate the performance of your initiative.

- Write an explanation of the logic behind your initiative.

Here’s another visualization of what that looks like.

Image Source: Wageningen University and Research

This planning model works best for organizations interested in taking on endeavors like building a team, planning an initiative, or developing an action plan. It’s distinct from other models in its ability to help you differentiate between desired and actual outcomes. It also makes stakeholders more actively involved in the planning process by making them model exactly what they want out of a project.

It relies on more pointed detail than similar models. Stakeholders generally need to lay out several specifics, including information related to the company’s target population, how success will be identified, and a definitive timeline for every action and intervention planned. Again, virtually any organization — be it public, corporate, nonprofit, or anything else — can get a lot out of this strategy model.

Example of the Theory of Change

For the sake of this example, imagine a business that makes HR Payroll Software — one that’s not doing too well as of late. Leadership at the company feels directionless. They think it’s time to buckle down and put some firm plans in motion, but as of right now, they have some big picture outcomes in mind for the company without a feel for how they’re going to get there.

In this case, the business might benefit from leveraging the Theory of Change model. Let’s say its ultimate goal is to expand its market share. Leadership would then consider the preconditions that would ultimately lead to that goal and why they’re relevant.

For instance, one of those preconditions might be tapping into a new customer base without alienating its current one. The company could make an assumption like, “We currently cater to mid-size businesses almost exclusively, and we lack the resources to expand up-market to enterprise-level prospects. We need to find a way to more effectively appeal to small businesses.”

Now, the company can start looking into the specific initiatives it can take to remedy its overarching problem. Let’s say it only sells its product at a fixed price point — one that suits midsize businesses much more than smaller ones. So the company decides that it should leverage a tiered pricing structure that offers a limited suite of features at a price that small businesses and startups can afford.

The factors the company elects to use as reference points for the plan’s success are customer retention and new user acquisition. Once those have been established, leadership would explain why the goals, plans, and metrics it has outlined make sense.

If you track the process I’ve just plotted, you’ll see the Theory of Change in motion — it starts with a big-picture goal and works its way down to specific initiatives and ways to gauge their effectiveness.

4. Hoshin Planning

The Hoshin Planning model is a process that aims to reduce friction and inefficiency by promoting active and open communication throughout an organization. In this model, everyone within an organization — regardless of department or seniority — is made aware of the company’s goals.

Hoshin Planning rests on the notion that thorough communication creates cohesion, but that takes more than contributions from leadership. This model requires that results from every level be shared with management — from the shop floor up.

The ideal outcomes set according to this model are also conceived of by committee — to a certain extent. Hoshin Planning involves management hearing and considering feedback from subordinates to come up with reasonable, realistic, and mutually understood goals.

Image Source: i-nexus

The model is typically partitioned into seven steps: establishing a vision, developing breakthrough objectives, developing annual objectives, deploying annual objectives, implementing annual objectives, conducting monthly and quarterly reviews, and conducting an annual review.

The first three steps are referred to as the “catchball process.” It’s where company leadership sets goals and establishes strategic plans to send down the food chain for feedback and new ideas. That stage is what really separates Hoshin Planning from other models.

Example of Hoshin Planning

For this example, let’s imagine a company that manufactures commercial screen printing machines. The business has seen success with smaller-scale, retail printing operations — but it’s realized that selling almost exclusively to that market won’t make for long-term, sustainable growth.

Leadership at the company decides that it’s interested in making an aggressive push to move up-market towards larger enterprise companies — but before they can establish that vision, they want to ensure that the entire company is willing and able to work with them to reach those goals.

Once they’ve set a tentative vision, they begin to establish more concrete objectives and send them down the management hierarchy. One of the most pressing activities they’re interested in pursuing is a near-comprehensive product redesign to make their machines better suited for higher volume orders.

They communicate those goals throughout the organization and ask for feedback along the way. After the product team hears their ideal plans, it relays that the product overhaul that leadership is looking into isn’t viable within the timeframe they’ve provided. Leadership hears this and adjusts their expectations before doling out any sort of demands for the redesign.

Once both parties agree on a feasible timeline, they begin to set more definitive objectives that suit both the company’s ambitions and the product team’s capabilities.

Strategic Planning Tools

There are additional resources you can use to support whatever strategic planning model you put in place. Here are some of those:

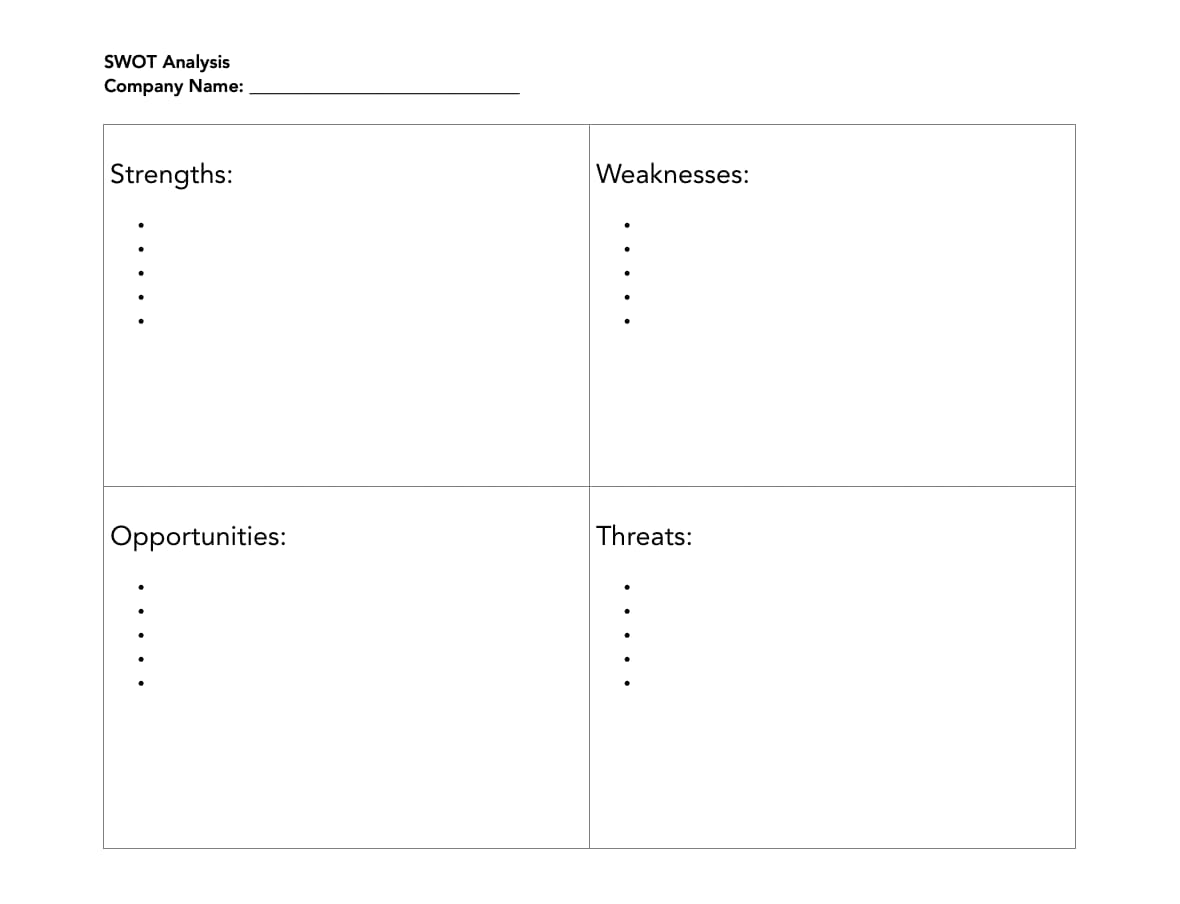

1. SWOT Analysis

SWOT analysis is a strategic planning tool and acronym for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. It’s used to identify each of these elements in relation to your business.

This strategic planning tool allows you to determine new opportunities and which areas of your business need improvement. You’ll also identify any factors or threats that might negatively impact your business or success.

Image Source: HubSpot

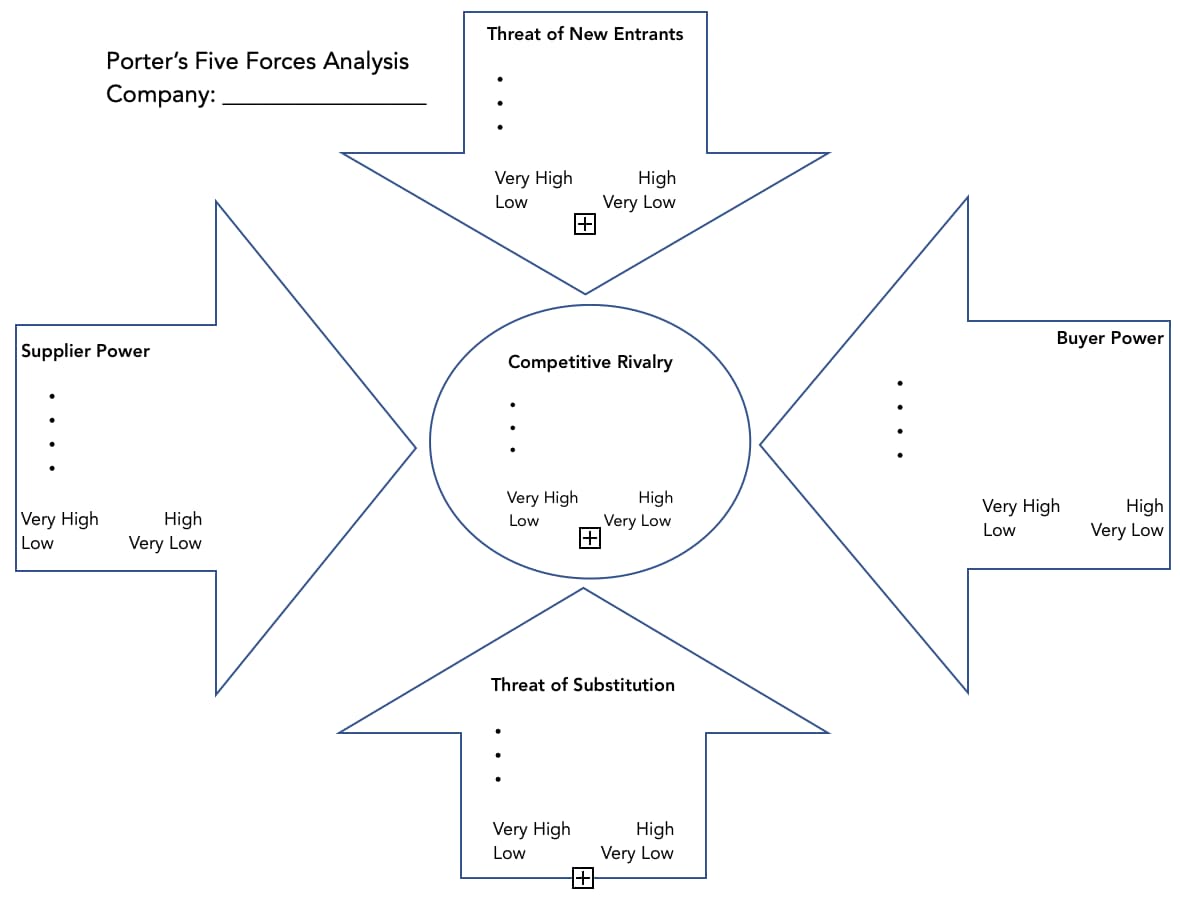

2. Porter’s Five Forces

Use Porter’s Five Forces as a strategic planning tool to identify the economic forces that impact your industry and determine your business’ competitive position. The five forces include:

- Competition in the industry

- Potential of new entrants into the industry

- Power of suppliers

- Power of customers

- Threat of substitute products

To learn more, check out this comprehensive guide to using Porter’s Five Forces.

Image Source: HubSpot

Image Source: HubSpot

3. PESTLE Analysis

The PESTLE analysis is another strategic planning tool you can use. It stands for:

- P: Political

- E: Economic

- S: Social

- T: Technological

- L: Legal

- E: Environmental

Each of these elements allow an organization to take stock of the business environment they’re operating in, which helps them develop a strategy for success. Use a PESTLE Analysis template to help you get started.

4. Visioning

Visioning is a goal-setting strategy used in strategic planning. It helps your organization develop a vision for the future and the outcomes you’d like to achieve.

Once you reflect on the goals you’d like to reach within the next five years or more, you and your team can identify the steps you need to take to get where you’d like to be. From there, you can create your strategic plan.

5. VRIO Framework

The VRIO framework is another strategic planning tool that’s used to identify the competitive advantages of your product or service. It’s composed of four different elements:

- Value: Does it provide value to customers?

- Rarity: Do you have control over a rare resource or piece of technology?

- Imitability: Can it easily be copied by competitors?

- Organization: Does your business have the operations and systems in place to capitalize on its resources?

By analyzing each of these areas in your business, you’ll be able to create a strategic plan that helps you cater to the needs of your customer.

With these strategic planning models and tools, you’ll be able to create a comprehensive and effective strategic plan. To learn more, check out the ultimate guide to strategic planning next.

Editor’s note: This post was originally published on May 17, 2019 and has been updated for comprehensiveness.

![Toni Kroos là ai? [ sự thật về tiểu sử đầy đủ Toni Kroos ]](https://evbn.org/wp-content/uploads/New-Project-6635-1671934592.jpg)